26 March 2024

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Morgan Sears-Williams explores experimental darkroom processes in her creative art practice including burying negatives and processing her film in caffenol. These alternative photographic methods allow her to embrace elements of chance and collaborate with the natural environment in exciting and unique ways. Shining a light on Hanlan’s Point, a significant queer space in Canada, Sears-Williams creates large scale photographs that showcase the erosion of the island and the precarity of it’s future.

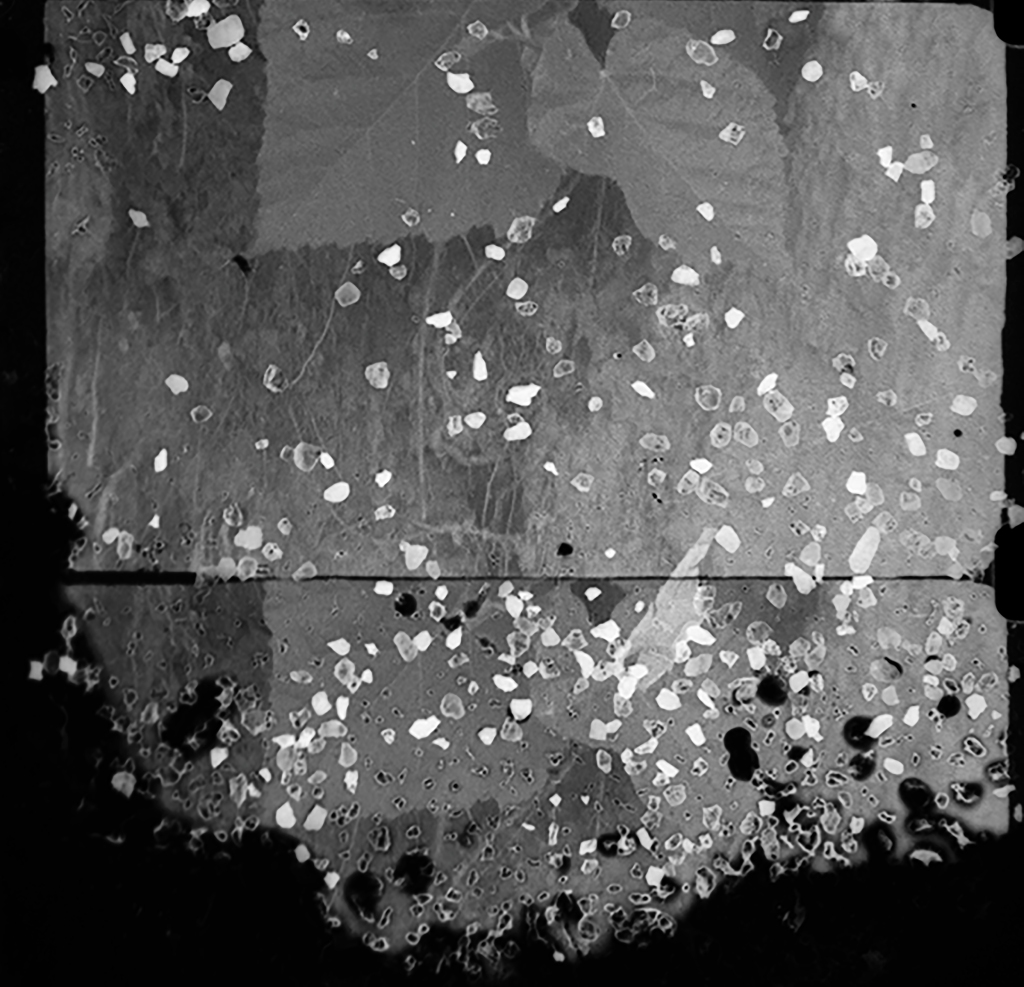

Morgan Sears-Williams, Buried Film (detail), 16mm, 2023

Elizabeth Ransom: Hanlan’s Point is the site of Canada’s first Pride in 1971 and one of Canada’s oldest surviving queer spaces. Can you tell us a little bit about the role Hanlan’s Point plays in your creative practice and what is currently happening to this historically significant location?

Morgan Sears-Williams: Hanlan’s point Beach and Toronto island have had a significant impact on my creative practice since I attended a residency at Gibraltar Point Centre for the Arts in 2016, led by island resident and artist April Hickox. The island itself has a small residential community with a large number of artists and activists, many of whom led the creation of Gibraltar Point Centre for the Arts which is housed in an old elementary school. When I attended a residency in 2022, island resident and artist Gaye Jackson led me through the area around Hanlan’s point. She spoke about the reasons for physical erosion, how the island has changed, the multitude of ecological habitats and the implications of the city of Toronto building new sections of the beach as preventative measures to the erosion.

Like you said, Hanlan’s Point was the site of Canada’s first Pride gathering in 1971 and is still an important gathering place for the city’s queer community. Meaning that this site has noted queer activity since the early 1900s. The Toronto Islands – where the beach is located – has faced significant physical erosion in the past 8 years due to numerous floods and the human-made alterations to the flow of Lake Ontario from the construction of the Leslie Spit headland off the east port of Toronto, which has been a known issue since the 1950s. In addition to the physical erosion, there has been an increase in homophobic violence in the past couple years, leading to a stronger feeling of the precarity of queer spaces in Toronto and across Canada.

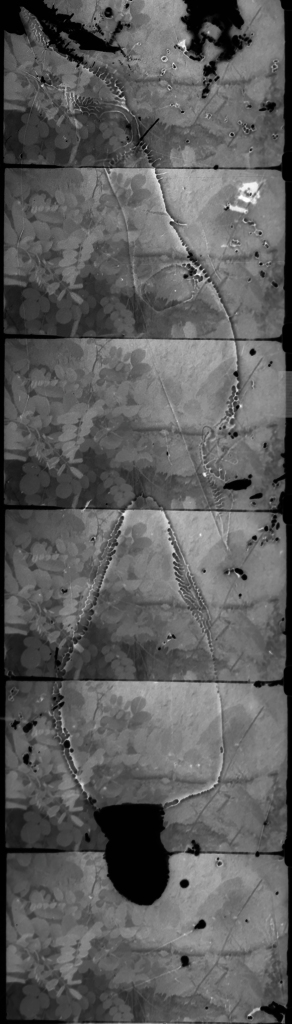

Morgan Sears-Williams, Buried Film, 16mm film, 2023

Elizabeth Ransom: In your practice you photographed the most visually eroded areas of Hanlan’s Point, processed the negatives in caffenol and then buried them in sand dunes. You work closely with the natural environment, physically imbedding the work into the sand dunes in collaboration with the land. How much does the element of chance play into this work?

Morgan Sears-Williams: Chance, play, and collaboration are key elements to my current work. I’ve worked in analog photography since I was 16, developing my film in my high school darkroom. As many darkroom artists know, there are a lot of elements that dictate whether you will get a clear image: developer time, water temperature, red light safety, properly fixing your negatives, light and exposure on the camera, among many other things. As much as we can narrow down these recipes and practices, there is always a chance that something has gone awry along the way and we are left with something we didn’t intend, or sometimes want. I am currently really leaning into the element of chance and how these can lead to unexpected, beautiful new possibilities of image making. It was a risk to put my entire 100ft roll of 16mm into the sand, but what came out were remnants of these encounters of emulsion with dirt, sand, ants, humidity and water. The image is now something that would be impossible to create by myself, impossible without leaving it to intuitive play and risk.

In many parts of this buried film, the sand has now morphed into the emulsion and can’t be removed. Leaning into the chances of what could happen is what made this work so special.

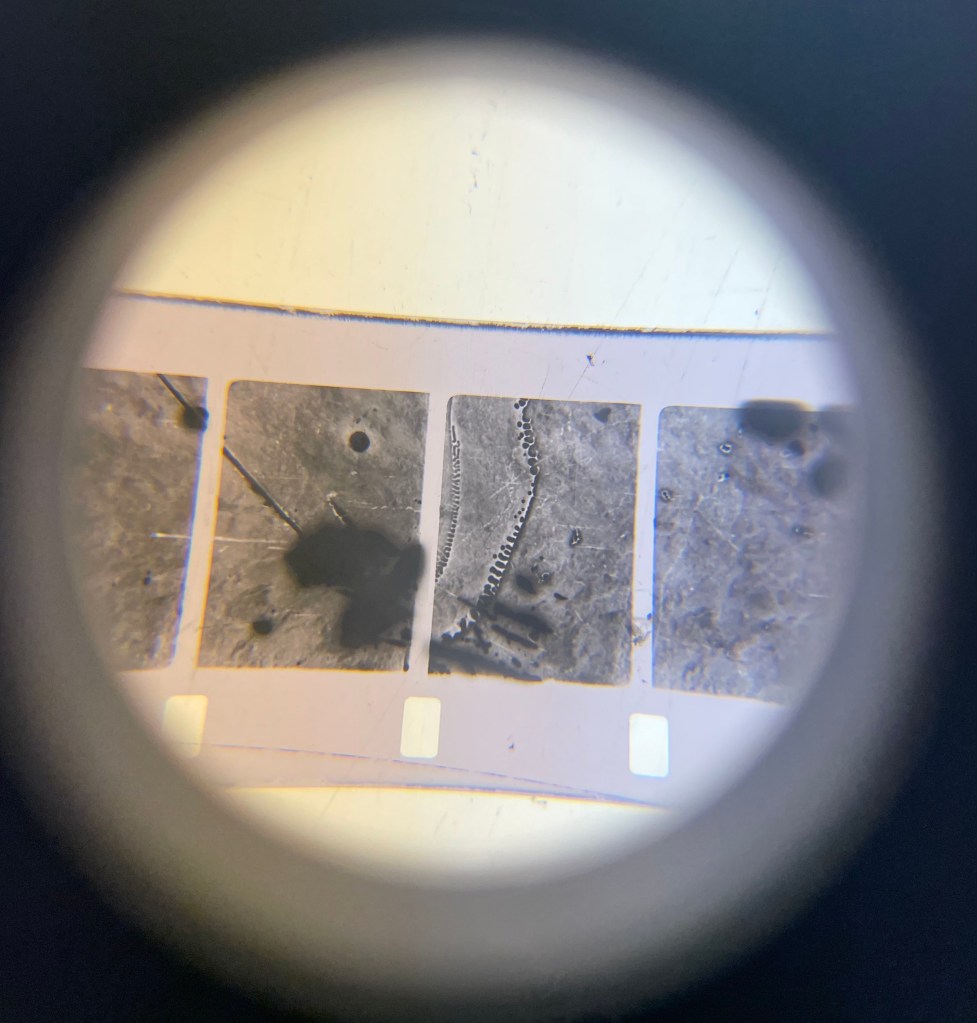

Process shot: optically printing the buried film, detail through loupe

Elizabeth Ransom: There is a certain preciousness that is traditionally associated with handling film negatives. We are taught to protect them by avoiding scratches and dust. However, in your practice you actively destroy the film embracing erosion and marks that show the human touch. Can you tell us a little bit about the response you have had to the tactile nature of your work and the way you handle your negatives?

Morgan Sears-Williams: Having worked in analog film for over 15 years, I think there is something special in knowing the rules and knowing how (and when) to break them. So much of my undergrad was learning how to handle negatives with care, how to dust them and avoid marks and scratches. Now that I am working more actively with film decay techniques, it’s interesting to see how people – artists and non artists alike – have a very strong, visceral reaction. When I was working on Toronto islands and buried my film in the sand, I made a TikTok titled “I buried my film in sand and this is what came out” a classic caption grab where, showing myself removing the film from the sand, throwing it in the lake to wash, and ending with scans of the decayed film. I had started TikTok a couple years ago as a way to share my process and film developing techniques. Knowing TikTok as a dystopian digital space which surveys, tracks, and learns our interests so as to create an algorithmic world view, I expected some engagement with my post and the regular amount of hate comments of simply existing as a woman on the internet.

After 3.6 million views, the comment section was riddled with people claiming that I destroyed this film, that it was a waste, that it ‘looked like shit’ (fire emoji), and had just wasted hundreds of dollars.

But, the visceral responses such as “this made me physically ill”, “I flinched”, or “this hurt”, are most interesting to me. Why did people feel so strongly about my touch on the film? It brings to light the ways we view, as a society, the ‘correct’ or ‘authorised’ way of handling certain materials. That film is seen as precious and fragile, but it is also resilient and durable.

This ‘non authorised’ way of processing and handling film is integral to my practice.

Morgan Sears-Williams, infinite kiss, 16mm film, 2023

Elizabeth Ransom: Much of your work deals with joy and desire as well as grief and loss of queer spaces. Can you share with us how you use alternative photographic processes to explore these themes?

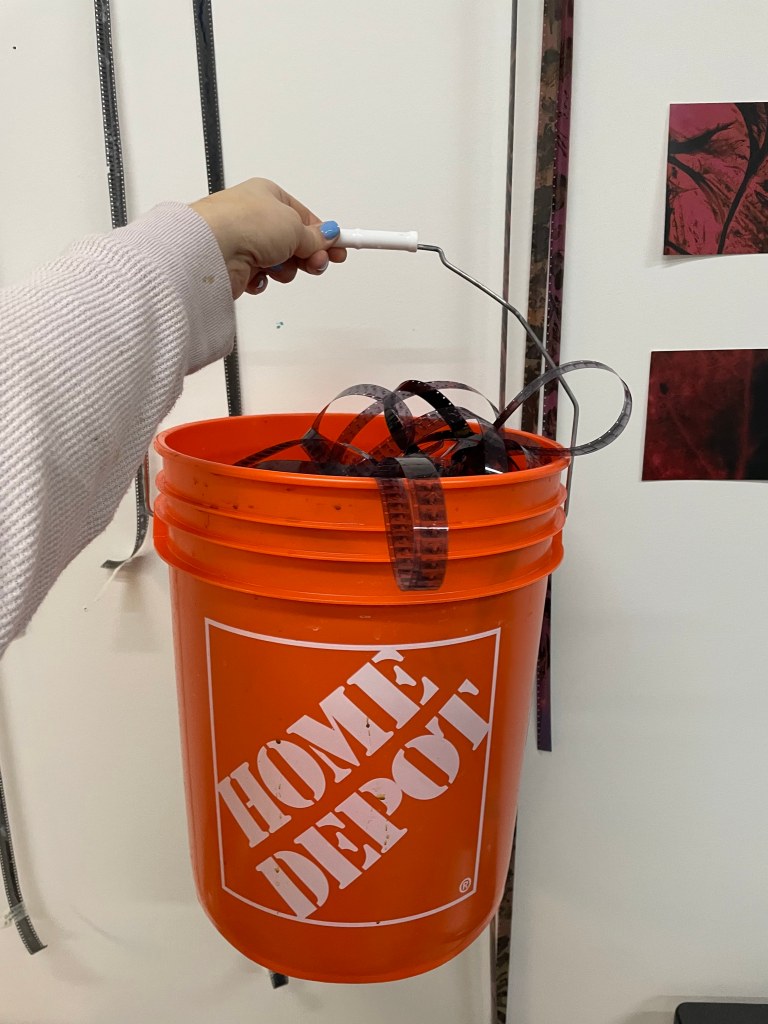

Morgan Sears-Williams: In my 16mm looped film infinite kiss, we see a close cropped moving image of two figures kissing, the frame is also riddled with marks and scratches made by bucket film processing. While film processing in a bucket, I wear gloves and continually agitate and move my film in order to ensure the developer is hitting all parts of the film. I feel my film collide against itself, my fingers in contact with the emulsion, creating artefacts and remnants of our encounters. These acts in the darkroom, by agitating more or less leads to both intentional and unintentional loss of the emulsion. Through this process, the aesthetics of the image are altered by the scratches and loss of emulsion, speaking to the personal erosion of the beach, the rise in hate crimes in the past couple years and the nuances in the loss of queer spaces. The images are bound together by fluids like saliva and film developer. The kiss mirrors acts of desire that occur in the private yet public cruising areas of the beach. These cruising areas in the bushes are just hidden but open enough for spectatorship or participation.

The alternative processes of caffenol and integration into the sand dunes use the process (burying in the sand, film decay) to mirror the erosion that is occurring physically on the beach and sand. In this sense, the consciousness of the land makes its imprint on the material, and both process and image remnants speak to the physical and personal erosion happening in this area.

The abstraction made by scratches on the emulsion and the grain on 16mm film allows room for ambiguity. These artefacts reflect the act of image making and the obscuring of queer bodies in a cultural landscape which constantly demands queer people defend their right to exist.

Process shot: bucket processing

Elizabeth Ransom: With the erosion of Hanlan’s Point beach and the increase in hate-related crimes targeting the LGBTQIA+ community there is a real risk of losing spaces for queer folks. What role do you think artists can play in aiding the protection of places like Hanlan’s Point?

Morgan Sears-Williams: For myself, I create out of necessity while also recognizing the power of art to change perspectives and mould public and interpersonal perceptions.

As artists we have a special role in moulding perceptions of space, time, experience and expanding our imaginaries to viewers. We can use art to speak to multiple social urgencies by focusing on a more sensuous form of understanding, one that focuses on a strong feeling or emotion that can bridge our intersecting and different experiences that we all hold.

For more information about Morgan Sears-Williams work please visit her website HERE

Morgan Sears-Williams, infinite kiss, 16mm film, 2023

Leave a comment