26 January 2026

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Artist Anne Eder constructs large scale creatures from moss, bones, and catkins found in nature. These monsters are recorded using alternative photographic processes such as anthotypes and salted silver prints. Anne weave’s fantasy and folklore into her installations. Through the creation of her mythical landscapes and fictional beasts, audiences are given space to escape to other worlds, reflect on the monstrous parts of themselves, and reconnect with the natural world.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your body of work, Sanctuary and Abjuration: Sentinels of the Ghostwood and Tales from the Fells, you create fantastical scenes using bones, moss, plants, and other objects found in nature. Could you tell us about the role mythology, folklore, fantasy, religion, and fiction play within your work?

Anne Eder: We are the sum of our fictions—the stories we consume as we grow up and the myths that underscore our religions and understanding of the world. Our sense of self is a delicately configured construct, rebuilt daily by telling ourselves the complicated tale of who we are, drawing on an archaic, faulty cache of memories. Myth, folklore, and religion are vehicles for explaining natural phenomena and parsing life’s big questions through fictional narratives. I see myself as an illustrator working at the intersection where the natural world meets the narrative impulse. I am interested in how specific geographies and geologies give rise to discrete myths and folklore, and in the role of the natural world in shaping our core mythologies, fables, and religions.

My best childhood memories are of being in the mountains and woods of West Virginia with my brother, left to our own devices. We would fish, catch insects to examine them, dig clay soil to make artifacts, collect rocks, and tell each other stories about monsters and bears. Mostly, we hiked, listened, and observed. Those woods were a safe haven, yet they also called to mind the Black Forest of the Brothers Grimm or the frightening thickets of Perrault’s Red Riding Hood.

I lived for the bookmobile to arrive, leaving each time with a tall stack of stories, from Beowulf to The Hobbit, and fairy tales of all stripes. I carried that interest with me as I grew up, immersing myself in multicultural mythology, such as Amos Tutuola’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and in comics like The Swamp Thing Saga and the Hernandez brothers’ Love and Rockets. As a grad student, I was incredibly fortunate to have Maria Tatar as a mentor, who has written many scholarly books on fairy tales.

I employ fairytale frameworks as a point of entry. The familiarity of the structure allows viewers to move into the work with ease. I use certain semiotically charged objects over and over—teeth and bones, flowers, ghosts, the wings of moths. I deal in monsters and in magic. These creatures are not intended to frighten, but to protect. The artifacts I create are presented as arms against a dangerous world and sinister forces.

Monsters take on a lot of cultural work. They can represent otherness, fear of the unknown, and our own binary nature. They exist in every culture, everywhere in the world. We may see the monstrous parts of ourselves reflected back at us, or we may see them as protectors or avatars. They are my teeth and claws.

Elizabeth Ransom: Your images often feel deeply rooted in nature. How does your relationship with the environment shape the fictional worlds you build, and in what ways does the landscape influence the types of processes you use?

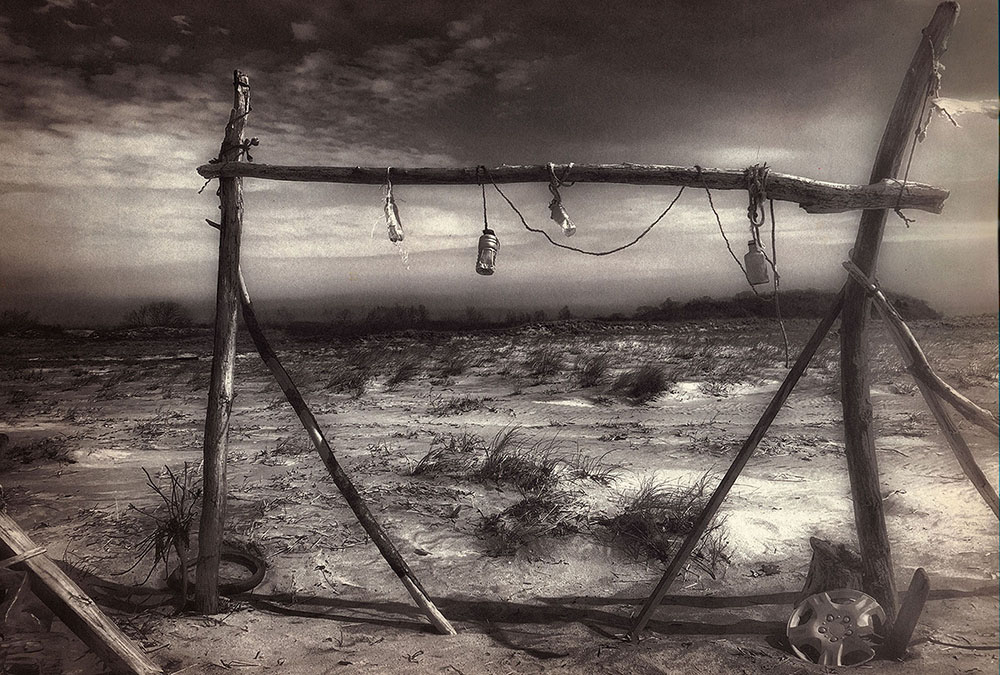

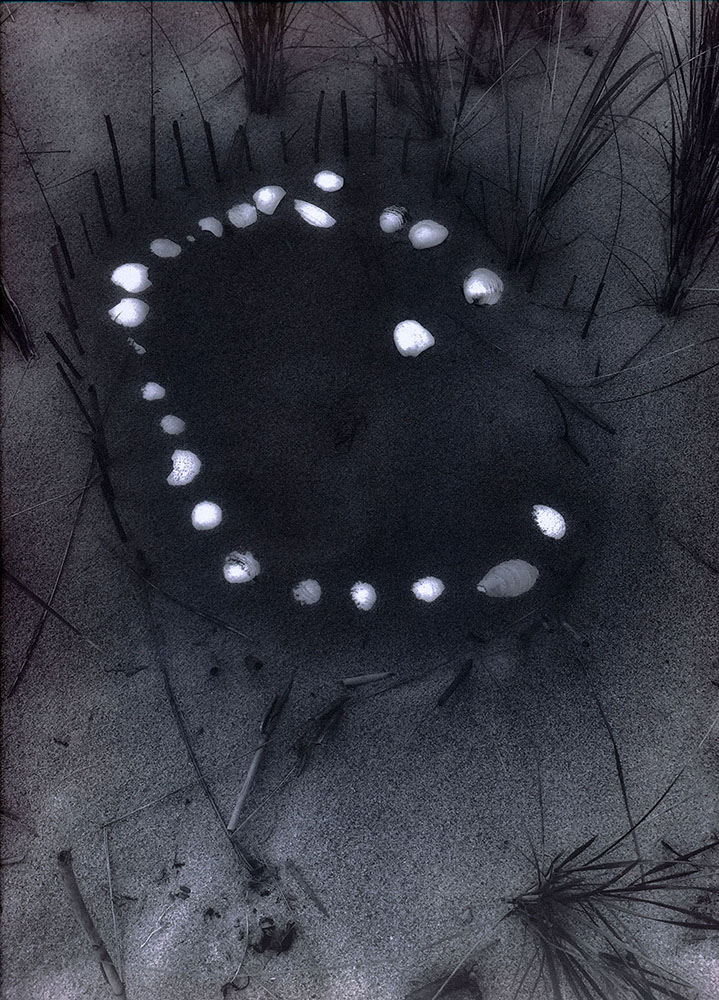

Anne Eder: Every ecological system has its own stories to tell and presents a distinct materiality to draw from. For example, as you mentioned, Sanctuary and Abjuration was mossy and plant-based, but Mysteries of Plum Island is set in an entirely different environment. The sandy textures and tessellations, the inhospitable climate, and the rhythm of the ocean demand a different expression. For that series, I used seawater to create salted silver prints, connecting them directly to the site by soaking my paper in the ocean. This met my requirement of relating to the site in a tangible way and introduced an element of the primordial, the inexorable. The sea as ancient and salty, the prints made using a salty and simple method. Impurities in the seawater also contributed to imperfections and tonal variations. Walking in Fox Talbot’s steps, I felt deeply connected to the medium of photography.

I have reached a point where I no longer want to contribute to the glut of commodities. I offer something experiential, tactile, and durational. Most of my sculptures are meant to decompose over time, and some of the print work is also ephemeral. My goal these days is reciprocity in practice– working in tandem with nature. In a time when our government is dismantling environmental protections, I try to reconnect people with the natural world through my art and teaching. I hope this may inspire stewardship.

Elizabeth Ransom: In some of your practice, you weave fictional narratives into your photographic work. What is your relationship between writing and image-making, and what does the act of crafting a story through the written word allow you to access or articulate within your visual practice?

Anne Eder: Writing doesn’t come as easily to me as generating a visual narrative. (I have two kids who are both brilliant writers. I don’t know where they get it!) The visuals and words tend to form symbiotically, the work of the hand triggering the imagination, which then loops back to influence how the physical work evolves. I think that if you look at the prevalence of fictional forms across nearly every culture, it is hard not to argue that they amount to some form of evolutionary survival mechanism. Stories can encode cultural biases, but they can also convey wonder, and by firing the imagination, they can foster resourcefulness and a connection to our environment. Stories show us not only the obstacles encountered by heroes and heroines, but also that those obstacles may be overcome. In other words, in stories, we find hope that problems may be solved and difficulties navigated.

Elizabeth Ransom: Within your images and also within the exhibition space you create large-scale creatures, talismanic objects, and theatrical environments. Could you talk about your process for physically constructing these beings and spaces on such a large scale.

Anne Eder: Every time I do a physical installation, I swear that in the future I will only make small flat art, haha! Yet the sculptures keep getting larger.

The recipe goes something like this:

3,500 teeth.

1200 willow catkins per bone.

2,600 protea seeds. 5,800 stitches.

Nine 9-foot ribs. 60 cubic feet of moss.

Deep dark woods, 8-foot tall plant creatures, the skeletal support of a fairytale.

I enjoy the construction, being outdoors, and the challenge of installing in different terrains. Each of my large monsters has a jointed body that can be positioned in expressive ways. Often site-specific, the materials themselves suggest the particular nature and personality of each one. On any given day, I might be making several hundred porcelain teeth, covering bones in soft willow catkins or crushed velvet flocking, or draping ten-foot armatures in 120 cubic feet of moss.

I take the substance of the natural world and transform it, meaning changing as the materials change, transmuting the real world into an allegorical one.

Elizabeth Ransom: In addition to creating large-scale creatures, you choose to photograph them using alternative photographic processes, such as anthotypes and platinum-palladium. Why do you choose to work with these processes?

Anne Eder: Sometimes it takes time to find the correct syntax for a body of work. One thing I discuss frequently in my classes is the connection between content and process. It isn’t always immediately clear. Tales From The Fells, and Sanctuary and Abjuration are a case in point. At first, I printed my moss giants in gum bichromate to achieve painterly, earthy greens and browns, but I was troubled by the disconnect between the organic materials and the use of toxic dichromates. I shifted to platinum and palladium because their long tonal range is ideal for the heavily shadowed style of my images. Chiaroscuro is the art of light and shadow, and the play of those opposites is at the core of my work, both physically and metaphorically.

Eventually, I settled on anthotype, juicing skunk cabbage from the location and using it as a light-sensitive emulsion. The prints were exhibited unframed, allowing the scent of the woods clinging to them to pervade the gallery space.

I think of photographs as objects, not merely two-dimensional, but as things you can physically hold and apprehend. Though I use some digital tools, the printing is generally done by hand. It is a language made up of metal salts, botany, alchemy, and the sun. Each process I use has a unique palette, texture, surface, and mood.

For more information about Anne Eder and her practice please visit her website HERE.

Leave a comment