31 October 2025

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Masha Pryven collaborates with young people in Narva, Estonia to question what it means to be human. Developed during a residency at the Estonian-Russian border, the project confronts the “institutional violence” inherent in state-defined identity and belonging. Through a multi-layered approach involving youth workshops, collage, polaroid, and public action Pryven challenges the audience to question the very notion of nationality and who gets to decide it.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your body of work Passport, you collaborate with youth participants to challenge institutional and personal beliefs surrounding identity and the symbolism of government documents. Can you tell us a little bit about what inspired this project and how you came to collaborate with young people?

Masha Pryven: I became an artist-in-residence at NART when I first went to work in Narva, Estonia, in January 2024. I had an idea of creating an object in the form of a book; it would be made from trash collected with local youth on the streets. At that time, I thought that another border area would be familiar to me because I was born and raised in Luhansk, a Ukrainian border city (occupied by russia in 2014). However, when I arrived in Narva, I was unsettled to discover the town’s conflicted identification with Estonia, predominantly russian-speaking and ethnically russian, it is still attached to Soviet and contemporary narratives from across the border. I hadn’t realized how physically close it was — only about 150 meters — a proximity that makes the town highly susceptible to its neighbour’s aggressive propaganda.

I realized that exploring Narva through its material remnants made sense — and that this exploration would also become my own research. I started looking for participants at a local art school, a youth center, also at the residency, which serves as a cultural hub and counterculture space in the city. Finally, a group of young people formed and we started meeting regularly.

Gradually, the participants started addressing issues that were relevant to their own lives in Narva: gender expectations, patriarchal social norms, Estonian citizenship, Soviet legacies – all through objects which they found in garbage or at their homes. We started a chat group, in which the youths shared photos and ideas, which extended the project beyond our meetings.

It was exciting to me how they engaged in social and political critique by reflecting upon found objects from the trash. Yet, during my time in Narva I often heard – from both youths and adults – that they were “apolitical” and had nothing to do with politics. This wide-spread attitude in Narva mirrors the russian state ideology of “non-interference in state power,” an approach that discourages civic engagement and helps enable ongoing war of aggression.

I wanted to challenge this attitude and returned in June 2024 for another project, Passport, supported by a scholarship from the Goethe Institute.

Narva as a trash book – object fragment, 2024

Elizabeth Ransom: You mention that this project reflects upon “the institutional violence ingrained in an ID document”. Can you elaborate on how the participants were invited to question definitions of self and assigned identities?

Masha Pryven: Narva became especially visible in the media, as russia invaded Ukraine in 2014. Estonia, a Baltic country, still recovering from the Soviet occupation, and a vocal supporter of Ukraine, has done a lot to counter the russian influence, for example, by establishing NART, an international residency, in 2014 to bring in perspectives and various voices to the city.

Local teenagers are very aware of the tension there, of how politicized their hometown is, many still without Estonian citizenship, with parents preferring to keep their russian citizenship. At the same time they are a new generation, like in any other part of the world, who just started finding out who they are.

So, I invited them to do two things — going beyond a received identity and nationality and at the same time to engage with one’s own rootedness into a larger political and social context.

We started meeting regularly, first once a week and then three, even four times a week, talking about the power of an ID document to include and exclude and ended up talking about what actually a human is. I gave impulses without pushing them into any philosophical discourses, just moderating their discussions. And it was fascinating to observe how they came up with an idea, similar to the 17th-century Descartian notion of thought, to define a human. They were developing that further, conversing about their lives, moral dilemmas, benefits and challenges of having a passport — and all that while cutting, folding, sewing their own passports.

Elizabeth Ransom: Each participant created their own version of a passport. What visual or symbolic choices were made when creating these personalised documents, and how did they reflect the participants’ own sense of identity?

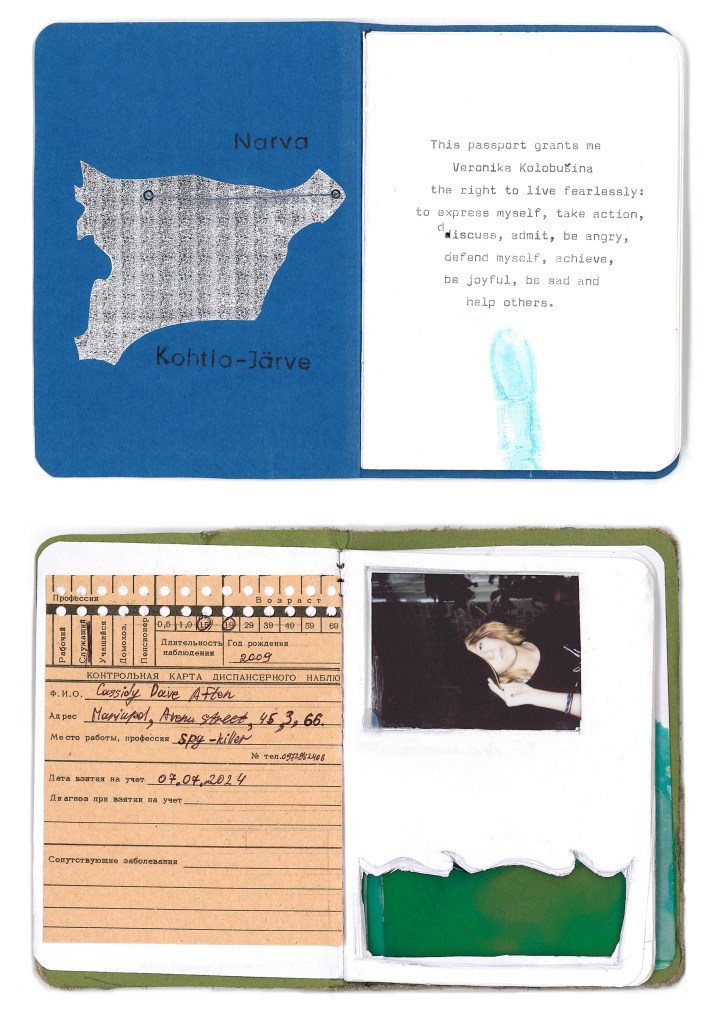

Masha Pryven: We kept the recognizable dimensions and shape of a typical passport, while re-thinking its major elements: a place of belonging vs a single country; a Polaroid photo vs an official identification portrait; an individual pledge vs an official preamble; self-chosen markers of identity vs the usual set of identifiers: name, age, gender, etc. At the end, they included a “constitution” as they called it – the same for all. In this text, they agreed as a group on what it means to be a human and denied the state’s authority to claim the passport as its property. As for the other pages, they were free to do anything they wanted to express themselves.

Their identity came to light through the specific choices they made. Interestingly, no one tied themselves to any country: Rein, native of Narva, made a passport of transition from the Soviet era to now; Polina from Ukraine who fled to Narva made a passport of memories centered on her hometown Mariupol, erased by the russian bombardments in 2022. Alisa, who fled russia with her parents, tied herself to a hybrid place – a combination of her hometown and Narva. Another participant, Veronika, who then moved to Tartu, created a passport of freedom, exploring and confronting her inner limitations.

Throughout the process, teenagers questioned how to move beyond purely aesthetic choices and ground their work in meaning – a search characteristic of artistic practice.

Passport — by Veronika Kolobušina, participant in Masha Pryven’s project, fragment, 2024

Passport — by Polina Kohut, participant in Masha Pryven’s project, fragment, 2024

Elizabeth Ransom: Passport included videos, polaroid’s, and collaged works. Can you tell us a little bit about the multi-layered approach and the various processes you used within this work?

Masha Pryven: I think of my approach as of radical participation because the final work evolves together with the participants. My initial idea was just to make passports. In the process, someone from the group suggested we show them in public. Where do you show work around passports in the border town? Of course, at the checkpoint border control. The idea was to engage people crossing into the European Union in conversation and ask the same questions that the participants asked themselves: What does it mean to be a human within state borders? According to our plan, the respondents who would stop to talk to the youths would receive a blank Passport of a Human, as an invitation to think about these questions.

We registered this intention with the Estonian police, which was not easy – I could not tell them that we would distribute passports at the border. It took some creativity to get permission.

I invited a local photographer to document this action, and it was her idea to videorecord interviews with the youths. I discovered those first when she sent them to me. For this action, I created various Passports of a Human, trying to engage with this idea myself.

Passport — interviews with participants just before the public action at the border checkpoint, video, 2024

Elizabeth Ransom: During the final public action participants took their passports to the Estonian-Russian border, engaged members of the public in a dialogue, and offered them a “Passport of a Human”. How was this action planned, and what did you learn from the public’s reaction to the exchange?

Masha Pryven: While planning, it turned out that I could not register this “political gathering”, as I am not a national of the EU and that we needed a person of legal age and with Estonian citizenship. Veronika, an 18-year-old participant, suggested that she would do that, which was an act of courage on her part – to be legally responsible for an action that could cause controversy. On the day of the intervention, the youths engaged people who were crossing to the EU in dialogue. A local radio journalist who interviewed me before the action could not quite place what we were doing and asked whether it was a performance or a provocation. I tried to explain that it was neither and the beneficiaries of the project were the youths themselves. They co-created a long-term art project that required commitment, they planned a public action and helped register it, found courage to talk to passers-by about it and ask questions, and gave interviews to Estonian TV.

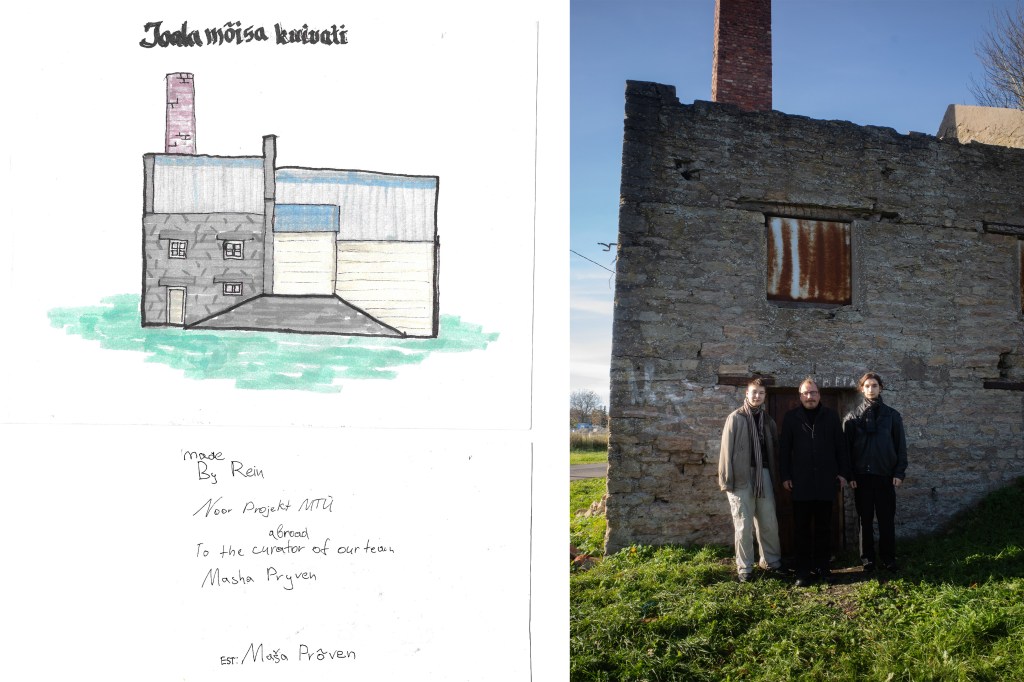

My goal was not to provoke people traveling between russia and the EU to think about their moral responsibility to counter injustice committed in their name. If that happened, that is fine. I worked with young Estonians simply to show them that they can participate in politics, engage with institutions, and create a conversation around their work. The biggest outcome of these two projects is that one of their participants, Rein Oster, now 19, initiated an art group NOOR PROJEKT (from Estonian: Young Project) and registered it as a non-profit association in 2025. As its leader, he has recently legalized an abandoned building in Narva and wants to turn it into an art center.

For more information about Masha Pryven and her practice please visit her website HERE.

Rein Oster (19), Madis Tuuder, Inspector for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Narva, and Ernest Zakirov (18) during our meeting to discuss the next steps of the renovation, October 2025

Leave a comment