29 September 2025

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

In the series Life Lines artist Ania Ready had the unique opportunity to take a deep dive into archival material and interviews that led her to discover the important story of Naomi Warren Kaplan. This inspiring individual survived Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and Bergen-Belsen during World War II. Naomi’s story is one of hope, survival, and resilience. Ania Ready uses the soil chromatography process to map the journey Naomi took from Poland to the United States as she seeked safety in new lands. This project was in collaboration with the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum and their partner, Holocaust Museum Houston.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series Life Lines you tell the emotional and important story of Naomi Kaplan Warren, a Jewish woman from Poland who survived three concentration camps where she lost most of her family during World War II. Can you tell us a little bit about this project and what inspired you to tell this story?

Ania Ready: This project was a collaboration with the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum and their partner, Holocaust Museum Houston. It began with the discovery of a note with addresses in the archive of Arthur Tyler, an Oxfordshire regiment soldier who helped liberate Bergen-Belsen concentration camp 80 years ago. On a folded piece of paper, Tyler had written the address of Naomi Warren’s (nee Kaplan) uncle in the US. Naomi, a Jewish woman from Poland who survived Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and Bergen-Belsen, had asked several soldiers to contact her family in America to let them know she was alive. Arthur Tyler was the only one who wrote down the address and followed through. This seemingly small gesture proved life-changing, enabling Naomi to reunite with her family in the US soon after the war and rebuild her life.

The note was discovered by Dr Myfanwy Lloyd, who worked with the Museum to include Arthur’s and Naomi’s story in their permanent exhibition. This, in turn, inspired an art project led by Anita Joice, where I and other artists were invited to respond to this remarkable encounter. Immersing myself in archival material, I was particularly moved by interviews with Naomi. Her story of survival, hope, and love resonated deeply with me. She spoke movingly about how the thought of seeing her sister again sustained her through the darkest times, and how that reunion eventually became a reality. I was also struck by her refusal to let anger define her life; she chose instead to focus on compassion and reconciliation.

In reflecting on Naomi’s life, I wanted to acknowledge her resilience and find a way to connect with her experience. I chose to use soil as a metaphor – something universal, grounding, and symbolic of both loss and renewal. After the war, Naomi’s hometown was no longer in Poland due to shifting borders, and she spent the rest of her life in the US, far from the land of her childhood. Through this project, I sought to trace her life’s path and, in a small, symbolic way, touch the soil she once walked on.

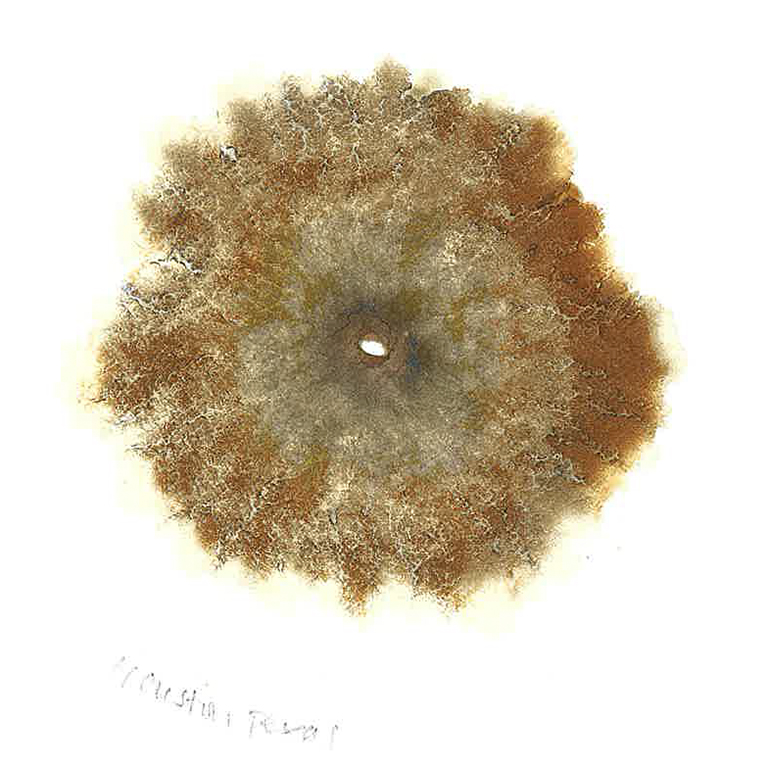

Elizabeth Ransom: Soil chromatography is a unique process that creates a photographic imprint of soil on filter paper. What is the significance of soil in this body of work, and can you share with us how you used this process to map Naomi’s journey from her birthplace in Wołkowysk (then Poland, now Belarus), Białystok, Warsaw, Paris, New York, and finally Houston?

Ania Ready: Soil, for me, represents something enduring yet often overlooked: both a silent witness to history and a symbol of what preserves. In this project, I wanted to tell a story of survival and resilience through something tangible and lasting. Each soil sample is unique in colour, texture, and composition, and each tells its own story.

To map Naomi’s journey, I reached out to friends, family, and colleagues in places significant to her life: her birthplace in Wołkowysk, Warsaw where she applied for a visa to the UK when World War II broke out, Białystok where she studied and met her first husband, Bergen-Belsen, and Paris where she obtained her visa to travel to the US. I also included New York, where she first settled and met her second husband, and Houston, where she raised her children, ran a successful business in a male dominated sector and became an art supporter and philanthropist.

Naomi often spoke about the importance of community – how survival in the camps depended on mutual support. I wanted to echo this spirit by asking people connected to these places to send a small pinch of soil, reflecting the kindness and generosity that shaped Naomi’s journey.

Collecting the soil samples also highlighted contemporary challenges, especially in obtaining soil from Belarus, given the current political situation and border restrictions. I was moved by the willingness of people to help, despite these difficulties.

The process of creating the chromatographs was fascinating. Each soil sample produced a distinct imprint, revealing its unique mineral composition and character. Some formed vivid patterns, others only a faint ring, but together they created a visual map of Naomi’s extraordinary life.

I also collaborated with my youngest daughter, playing with soil from Warsaw she held – a place of connection between Naomi and me (Naomi was awaiting a visa to the UK there before the war; I was in Warsaw, embarking on my professional life after graduation). My child’s tactile curiosity, for me, formed a quiet meditation on belonging, connection, and emotional geography between past and present, homeland and diaspora.

Elizabeth Ransom: Your work Life Lines engages deeply with the historical trauma and resilience embedded in Naomi Kaplan Warren’s story. Could you speak to how the historical significance of her journey shaped your approach to materiality, site-specificity, and visual storytelling?

Ania Ready: Naomi’s story profoundly influenced my approach to materiality and visual storytelling in Life Lines. I wanted to create an imprint, something tangible that would honour the physical and emotional landscapes she traversed. The project involved engaging with powerful archival material, including images and footage from the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. As a Pole, I grew up learning about Auschwitz and the Holocaust, but handling these archival materials brought a new, deeply personal perspective to the work.

Rather than simply retelling Naomi’s story, I aimed to evoke her spirit and resilience through the materials themselves. Like her, I didn’t want to focus on the dark side of humanity. Soil became a central motif: each pinch of earth represents a fragment of memory, a geography of survival and endurance. Collecting these soil samples from places significant to Naomi’s life, with the help of many collaborators, was one of the most moving aspects of the process. It demonstrated how acts of kindness and cooperation can bridge distances and create something far greater than any individual effort.

I wanted visitors to physically engage with the work – to touch the soil, to notice its different colours, textures, and weights. Each sample in the installation is accompanied by a fold-up paper containing an archival image from Naomi’s life, along with her story and the story of acquiring the soil. Through this tactile, site-specific approach I wanted viewers to connect with Naomi’s life not just intellectually, but through their senses, making the historical trauma and resilience embedded in her story more immediate and real.

Elizabeth Ransom: As someone who has experienced migration first-hand, how do you think about place, not just as geography, but as memory, emotion, and belonging when constructing a narrative around migration?

Ania Ready: I moved to the UK twenty years ago to live with someone I fell in love with, and for me, migration is not just about crossing borders or languages; it’s a deeply sensory and emotional experience. Place becomes layered with memory, longing, and the ongoing search for belonging. There’s a sense of loss and disconnection from the country you leave behind, and the gradual realisation that you can become a stranger to your own homeland, witnessing its changes from afar.

Migration is also about new sensations: unfamiliar smells, the feel of different winds – here in the UK, frequent storms have replaced the Baltic winds of my childhood. Even the soil underfoot is different; it’s what we walk on, what we grow plants in, what we breathe in, and it shapes our daily lives in subtle ways. I used to love standing on the Baltic shore in my hometown of Gdynia, watching the endless movement of the water and the limitless horizon. Living near Oxford, far from the sea, I eventually found a substitute: watching the vastness of the fields, the wind moving through the crops and grasses in a way that reminded me of the constant motion of the sea. My sea here is the sea of greenery around me.

Migration means building a new world, often starting with a small circle of family and close friends. The family I have here has become my anchor and shaped my sense of belonging. I’ve become part of a different history and a different land, gradually weaving myself into the fabric of everyday life in England, and watching my children navigate their mixed heritage – Polish, English, and Italian.

All these experiences shape how I think about place in my work. It’s not just geography; it’s a tapestry of memories, emotions, and sensory impressions, all woven together in the ongoing process of growing, finding oneself, and discovering new meanings of home.

Elizabeth Ransom: Within this project you are working with archival images as well as alternative photographic processes. How do you use these unique processes to share the emotional landscape of this story and why did you choose to work with these processes as opposed to others?

Ania Ready: Working with archives and alternative photographic processes allows me to explore the past in a way that is both investigative and deeply personal. I am naturally curious, and archives satisfy my desire to uncover, question, and understand how individual stories and collective histories are constructed. My background includes working with literary archives and historical photographs, often related to female figures, which has shaped my approach to visual storytelling.

I am drawn to alternative photographic processes because of their unpredictability and uniqueness. Unlike digital photography, these methods introduce an element of chance and materiality: each work is one of a kind, shaped by the process itself. This mirrors the emotional landscape of the stories I work with, where memory and experience are often fragmented, layered, and imperfect.

By combining archival images with these experimental techniques, I try to evoke the complexity and depth of the narratives I’m sharing. The tactile, hands-on nature of alternative processes helps to convey the emotional resonance of the past, making the viewer more aware of the passage of time and the fragility of memory. I chose these processes precisely because they allow for a more nuanced, evocative, and intimate engagement with history than more conventional methods.

For more information about Ania Ready and her practice please visit her website HERE.

Leave a comment