28 May 2025

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Lumen prints are made by exposing silver gelatin paper to light for extended periods of time. This unique photographic process does not require a camera or a darkroom, but instead relies on light from the sun. Galina Kurlat, known for her use of lumen printing, creates painterly like images that are striking in their appearance. The vibrant colours that she creates mesmerises audiences while also exploring feminist issues surround the female form.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series Charting the Hours you place hair, saliva and blood directly on to the photographic paper to create abstract images. Can you tell us a little bit about this project and how the pandemic impacted your creative process?

Galina Kurlat: This series began early on during the Coronavirus pandemic. I found a combination of my and my partner Adam’s hair in the shower drain, this prompted me to think about the amount of time we were spending together during lockdown. Our two bodies co-existing in a Brooklyn apartment in a way that we had never imagined before this moment in time. What was the evidence of this intense time spent together?

Using our hair, spit, blood, urine, and nail clippings I began to make lumen photograms of these remnants. This distillation of the body’s presence seemed like a breakthrough, an affirmation, evidence of existence. My early prints were small experiments using only window light, exposed for hours and sometimes days. I made these images in the interiors we occupied with consideration to the light we experienced, day in and day out.

Elizabeth Ransom: Your body of work Vestige continues to use the human form but instead this time your body directly comes in to contact with the surface of the print, creating abstract interpretations of the female form. Can you tell us about how this project confronts the objectification of women and what inspired you to create work that deliberately defies traditional depictions of the female body?

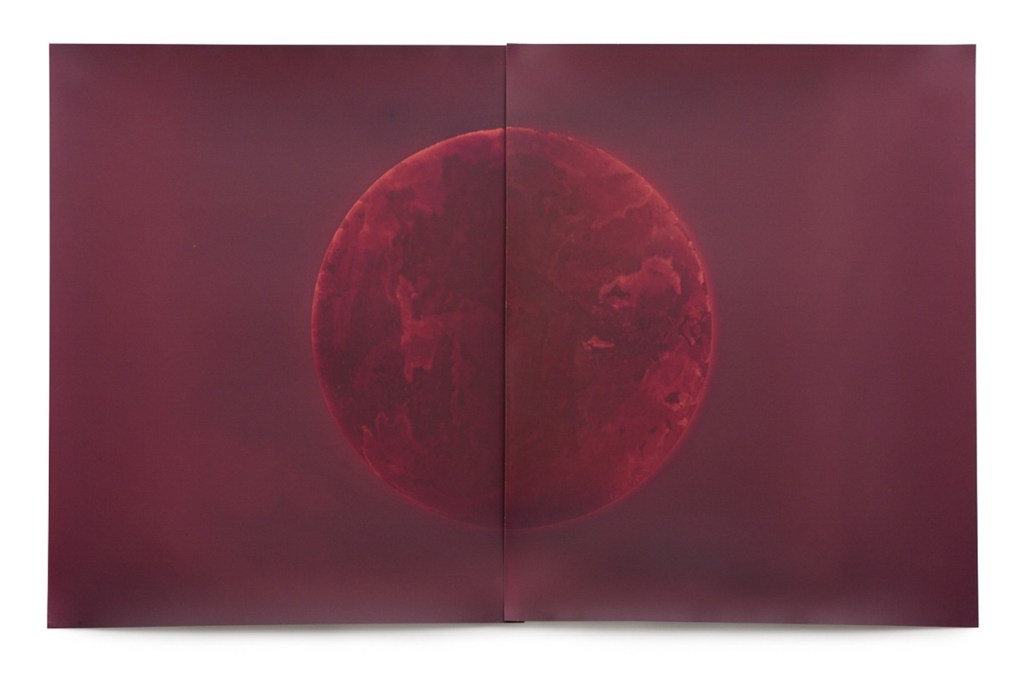

Galina Kurlat: In my current work, Vestige, the body is absent, but referenced through the color of the photographic paper and trace material from my body, which interacts directly with the photographic paper. By using materials from the body; blood, breastmilk, hair, and bathwater I engage with both the concepts and materials employed by feminist artists; a missing body is prominent in Senga Nengudi’s pantyhose pieces, filled and bulging with fabric and sand, in Kiki Smith’s Untitled 1987-90, twelve water-cooler bottles, silvered to a mirror surface, are each engraved with the name of a different bodily fluid: blood, tears, urine, milk, and in Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) (1989) a positive and negative portrait of a woman looks directly at the camera as the words “your body is a battleground” are collaged in the center in Kruger’s iconic font.

Although my works are deeply personal and specific to my experience, there is a through-line to the current political climate in the US. The female body is once again a battleground. Political forces dictate what is and is not a medical procedure to the detriment and at times, fatal consequences of women. The rights I assumed were permanent growing up, are currently under direct attack or have already been revoked. During the making of these pieces, I was pregnant three times and had two babies. For me, these self portraits are as much about the body as they are an opposition to the many oppressive political forces currently moving in on our rights as women and birthing people.

The female body, which has been used a muse throughout photographic history is specifically absent from these self-portraits. This elimination of the body is not an omission of self, but rather a subversion of the male gaze and a redirection to the sublime. Abstract traces of the body, and the materials used to make the images stand in stark contrast to the male centric depiction of the nude.

Elizabeth Ransom: Both Charting the Hours and Vestige use the lumen print process. Can you tell us about this method and how you manage to create such vibrant colours in your work? Do you choose to fix the images?

Galina Kurlat: I chose my materials with a specific color palette in mind, which references the body’s interior and exterior, and I am excited by the potential in silver gelatin papers. Exposed for extended periods of time the various colors deepen resolving in muted pinks, mauves and reds. There is a direct correlation between the concept of these works and the materials I chose to print with.

Over the years, I have narrowed down the specific quality of light, type of paper, and UV levels I like to print in. There is still a lot left to chance in my practice, but this careful selection does give me a good starting point to know what the final outcome might be. As with any abstract process, there are a lot of pieces that almost make it to the final selection.

I do fix the prints, which can lead to some disappointment due to loss of contrast and change in color, but that is all part of working with lumens.

Elizabeth Ransom: Your work embraces imperfections and chance. How do you balance control and unpredictability in your creative process?

Galina Kurlat: Initially, I was attracted to alternative photographic processes because of the unpredictable nature of the materials. There is always room for the medium to speak and to have a say in the final outcome of the piece. This dialogue has been an ongoing part of my practice for many years. I try to value the materials I am using and learn as much as I can from them, with the hope that they allow me to make the work I need to make.

Elizabeth Ransom: With the use of alternative photographic processes, your practice often emphasizes materiality, imperfection, and transformation. Do you think it’s possible for these methods to offer a unique way to convey feminist ideas in particular when referencing the representation of women?

Galina Kurlat: When I think of the artists working in alternative processes today, almost all are women. Although photography itself is a male dominated medium this particular space has so many powerful, creative and inspiring women and female identifying artists practicing in it. I cannot say with confidence that any one medium offers a unique way to explore feminist ideas, but seeing so many inspiring women working with tangible photographic materials in a contemporary way is exciting for the future of alternative processes.

For more information about Galina Kurlat and her practice please visit her website HERE.

Leave a comment