24 April 2025

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

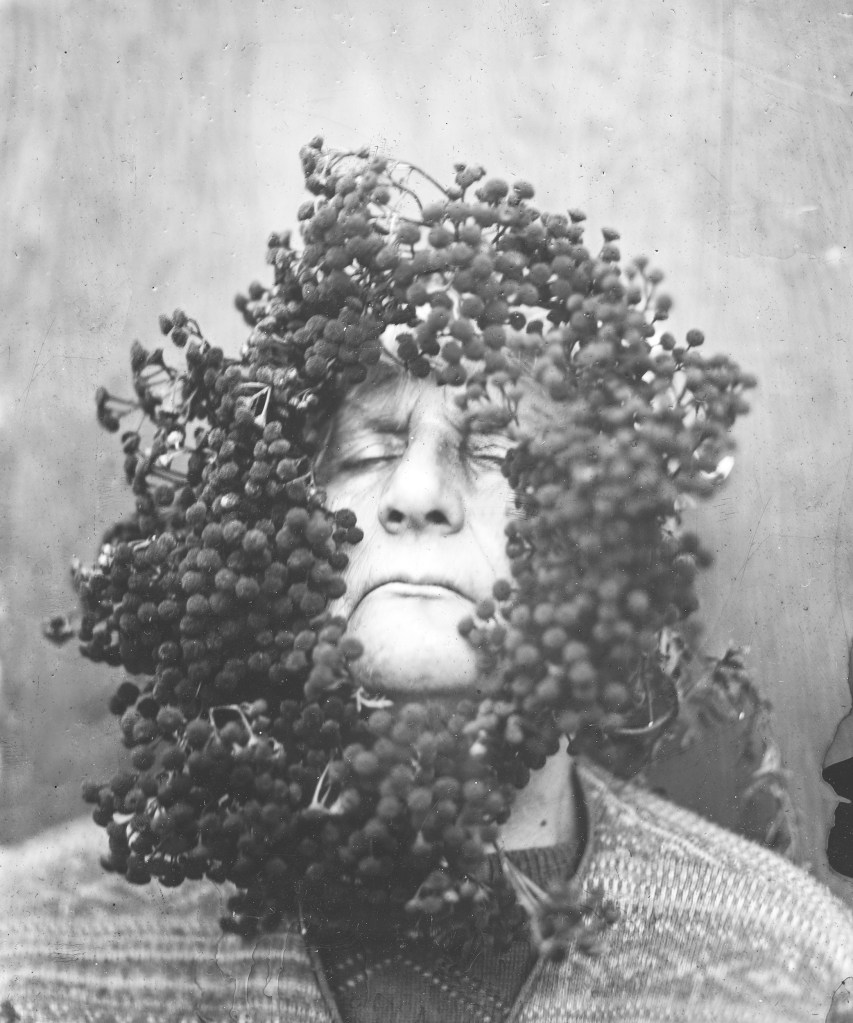

Inspired by heritage, family, and memory Magda Kuca tells stories exploring foklore and Slavic rituals. Magda collects plants, herbs, and archival material from Poland and brings them back to her studio in London to create visually striking images. These black and white photographs are formed using historic processes such as wet plate collodion and gum bichromate. With the help of the women in her family, Magda investigates her Polish heritage through Slavic customs and beliefs.

Elizabeth Ransom: What drew you to alternative photography techniques like wet plate collodion, gum bichromate, and chlorophyll printing, and how do they shape your storytelling?

Magda Kuca: What drew me in at first was the magic of it all— processes I work with have a presence. They’re messy, physical, unpredictable… they ask you to slow down, to be fully present. With collodion, there’s this moment where an image appears- out of the chemicals, the darkness-it’s alchemy.

I think that slowness really influences how I tell stories. Processes I use aren’t just techniques—they are part of the narrative. The imperfections, the fingerprints, the labor—it all becomes visible. For me, it’s about making something with your hands from scratch, something that holds memory, time, and care. A digital image doesn’t always give me that same emotional weight. I like that my tools are old, tactile and flawed—it keeps the work honest.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your project The Grandmothers, you create wet plate collodion images influenced by Slavic rituals. Could you tell us a little about these rituals and how your work reflects heritage, memory, and folklore?

Magda Kuca: The Grandmothers is really where my journey into using wet plate photography to explore heritage began. It’s a series of portraits of my grandma—framed through the lens of Slavic customs and beliefs. She holds an almost mythological presence. The images are often stark, symbolic, and quiet—showing gestures, herbs, textiles, and motifs rooted in the feminine and the ritualistic.

Grandma’s presence gives a sense of protection and wisdom. The Presence of dried herbs drawn from herbal medicine, house she used to work with in the middle of forest, now decaying and empty-all of these are visual echoes of rituals tied to healing, protection and remembrance. I’m drawn to those blurry lines between what’s real and what’s spiritual, between what we know and what’s been passed down in stories or instinct. Rather than illustrate specific customs, these works try to evoke the sense of spirituality, folklore, tradition and reflect on those in a broader sense, one that my audience can resonate with whether they can relate to the Slavic culture with their own experience or whether is foreign to them.

Last year, I gathered ten years of this and other works into a book called Tales. It felt like stitching together a quilt-one that weaves together family, folklore, and a sense of home. I was honoured to have Martin Barnes, Senior Curator of Photography at the V&A, contribute the foreword- he described the images as visual fables in which the world of humans, animals, plants and objects meet in a space where time is porous and suspended which, to me, captures why I’m drawn to historic photographic processes. They allow for a kind of stillness, where the stories linger, shimmer, haunt and leave something for the imagination.

Working in wet plate felt right for this—it’s slow, physical, and imperfect. The silver on glass is otherworldly and each plate becomes like a keepsake or a relic. Its about grounding these ideas and many women that my grandma impersonates in something tangible and making them visible and present in a world that often forgets them.

Elizabeth Ransom: Familial relationships, ancestry, and memory are key themes in your work. Can you talk about the influence your family has had on your photography?

Magda Kuca: My family, especially the women, are woven into many aspects of my practice. My grandmas, mum, great grandma are not only subjects, they’re the keepers of stories, the ones who hold onto the rituals-they are my anchors to the past. Photographing them was a shared ritual in itself. When I first started making wet plates with my grandma, we had no idea what would come out. The plates were often full of chemical stains or would barely show a face—but slowly, something emerged as I developed my skills in this demanding craft. It changed how I saw photography: as a way to connect. To remember. To collaborate. There’s something powerful in using an old process to trace a personal history.

Elizabeth Ransom: In Family Tales, you combine archival materials with historical processes. How do these materials influence your themes, and how do you reinterpret them to create new dialogues?

Magda Kuca: Family Tales is built around personal archives—old photographs, objects, fragments of letters—and my attempt to make sense of them through replicating and reprinting them. Instead of restoring or preserving them in a traditional way, I work with their brokenness. I reprint them using gum bichromate, wet collodion, and chlorophyll—each process distorts, stains, and alters the material. It mimics how memory works—how it fades, gets rewritten, or even imagined.

Some of the images are portraits of family members; others are new works that I responded with based on oral stories- for me, they carry emotional weight. The way the emulsion lifts, how the print breaks apart or seeps into a leaf, all of that is part of the language of grief, resilience, and love.

The photographs are less about telling a linear family history and more about exploring how these intimate narratives live inside us. It’s emotional archeology. I’m not just showing my own family’s story—I’m inviting others to reflect on what their own fragments might look like.

Elizabeth Ransom: Your Polish heritage plays a key role in your practice, especially through materials collected during visits to Poland. How has migration affected your creative work?

Magda Kuca: Living in London, away from Poland, has actually made me feel more Polish in a strange way. The distance creates this longing, but also a sharper awareness of what I carry with me. When I go home, I’m not just visiting—I’m gathering, collecting, researching. Even something as simple as picking leaves for chlorophyll prints becomes loaded with meaning. Those materials become part of the work, part of my storytelling.

Migration also makes you think about what gets lost, what gets held onto, and what you need to invent to feel whole. There’s a sense of creating your own mythology, your own way of bridging the past and the present.

London, with all its chaos and creativity, has become the place where I build that mythology. Working as a full-time artist here, surrounded by other migrant voices, has shown me how heritage is not fixed—it evolves. Sharing my craft through workshops—whether it’s wet collodion, gum bichromate, or botanical printing—has become a core part of my creative life here and a way to make a living in a challenging city like London. I get to teach these beautiful, old techniques to others, which feels like passing something on. It’s about keeping the conversation alive.

For more information about Magda Kuca and her practice please visit her website HERE and you can check out her photobook Tales HERE.

Artist portrait by Adam Juszkiewicz

Leave a comment