3 April 2025

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Isabella Marie Garcia facilitates joy in her community workshops with folks in the juvenile justice system. These workshops involve poetry, cyanotypes, anthotypes, and other experimental processes that allow participants to explore their identity and tell their own stories. Through this important work Isabella investigates agency, representation, and the ethical implications of working within carceral systems.

Elizabeth Ransom: Could you tell us a little bit about the workshops you run with women and non-binary people that teach experimental photography techniques in correctional facilities, residential rehabs, and alternative schools?

Isabella Marie Garcia: Absolutely! I’ll disclose that I have yet to run a workshop with another photographer, but would love to if the opportunity presented itself. I began teaching experimental photography in these spaces when I was seeking teaching opportunities in Miami that centered the visual arts.

My initial teaching experience began in 2022 through O, Miami at Brucie Ball Education Center in Kendall where I worked with neurodivergent, non-speaking students to create mixed media poems. This program was guided by the leadership of Donnie Welch and Raquel Quinones. We worked with various prompts and I provided tactile materials for non-spoken, wheelchair-bound poets to interact with and bring poems to life. This then evolved to a year of shadow training and then lead teaching work as an O, Miami Sunroom Poet at Title I schools such as Charles R. Hadley Elementary in Westchester, where I worked with ESOL students and aided their poetry via Spanish to English translation, and Morningside K-8 Academy in Little Haiti.

Seeing an open call for teaching artists during the summer of 2023, I learned of the ICA Narratives program that is organized and run through the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. The program centers the theme of identity as a platform for participants to express their own stories through creative work. Familiar with artists who were previous teaching artists for the program, I applied and was accepted for an interview with Jessica Helsinger, the Site Coordinator, and Alyssa Panganiban, the Community Programs Coordinator in late August.

During the virtual interview, I soon learned that the students I’d be working with were at-risk and incarcerated youth. Not specifically mentioned on the initial application page, the populations would also be physically located all over Miami-Dade and Broward County. Having taught students who rest in unconventional circumstances, I was open to the challenge and was asked by Jess and Alyssa to develop an eight week curriculum with a supply list and breakdown of each lesson.

Originally hoping to teach 35mm film photography, I adapted my curriculum towards experimental photography in order to adhere to the rules and regulations that come with teaching students in the juvenile justice system. The juvenile justice system is a separate system of criminal justice for children and young people under the age of eighteen, accused of committing crimes. Ironically, with the theme of identity in mind, the students’ faces and likeness can not be photographed. Many of the students I met in my teaching year were in a mixed bag of circumstances: they are minors, going through criminal court trials that are sealed in confidentiality when it comes to their image, and many of which are in the foster care system within the state of Florida, making them wards of the state.

I did my research on experimental photography, a lens-based medium I had never worked with before, and developed a curriculum that thought about displacement in South Florida as a theme in which to respond when executing these techniques. Thus, Uprooted: Alternative Photography in Ekphrastic Conversation was born.

Accepted to teach, I taught in the fall at a residential rehab in Pembroke Pines called Citrus Health, which treats youth going through substance abuse addiction, mental health disorders, and foster home transition. Finally cleared in background paperwork by the spring, I taught four sites from February to April 2024— Miami-Dade Juvenile Detention Center (DJJ), AMI Kids Miami-Dade Key Biscayne, Girl Power Overtown, and Urgent, Inc. Brownsville.

Across the eight weeks at each site, I taught the students how to build and decorate their own pinhole cameras using cardboard boxes, making portrait zines and using collage to describe yourself, oil-based photo transfers using ink-jet printed images and essential oils, small-scale cyanotypes on fabric with a UV lightbox and clear transfer sheets that can be written on, anthotypes using turmeric and achiote powder mixed with rubbing alcohol, large-scale cyanotypes on cotton blankets, chlorophyll printing on banana leaves, and photo critiques of one another’s work.

Culminating in a student exhibition titled UPROOTED that was on view at ICA Miami from April 20 through July 31, 2024, the theme of displacement through immigration via exile, climate gentrification, race and gender-based daily systemic issues, neurodivergence, ableism and disability in the world, were key subject matters to read through and consider while visiting the exhibition. The Narratives team and I painted the room orange and blue as a call to Miami’s palette, placed street signs with the names of the neighborhoods our students were from, and Sterling Rook, an artist who previously taught with the program, helped us build a house that we then covered in body-based cyanotypes created by the students, marking it with a for sale sign as representing the high cost of living and housing crisis in Miami.

The UPROOTED workshop series extended past my ICA Narratives teaching into a week-long class I applied and taught as faculty at School at the Alternative in Black Mountain, North Carolina in May 2024. Then in October and November 2024, I merged experimental photography with poetry lessons to teach a four-week workshop program to a group of participants through O, Miami, which builds community around the power of poetry through collaborations.

A cyanotype on cotton artwork created by an AMIKids Miami-Dade South Key Biscayne student during the ICA Narratives 2023-2024 program. Image by and courtesy of Chris Carter.

Elizabeth Ransom: Why do you choose to work with experimental photography techniques as opposed to others?

Isabella Marie Garcia: My entry into photography was through playing with a digital camera here and there, and then a 35mm black and white darkroom course I took with Mirta Gómez del Valle during my senior year as an undergraduate at Florida International University. That started an obsession with being in the darkroom and shooting analogue film that has not stopped.

I still love analogue film now six years out of undergrad, but began working with experimental photography techniques out of necessity when I taught with ICA Narratives. I had never practiced experimental photography before then, but in order to teach my students, I had to teach myself.

I spent hours researching what experimental photography techniques would be the clearest and safest to teach to my students, mainly on https://www.alternativephotography.com/. It’s an amazing website for self-educating yourself on the ABCs of experimental photography. The students I worked with couldn’t use sharp or hazardous materials that they can harm themselves with, so I taught myself how to pretreat yards of cotton fabric with cyanotype and anthotype recipes to then bring it into the classrooms with a darkroom film changing bag.

In teaching myself to teach others, I appreciate how experimental photography feels akin to the magic of making a camera-based image. The classic cyanotype process utilizes the intensity of the sun to process images over a gradual period of time, as do anthotypes that use nothing but juice extracted from the petals of flowers, the peel from fruits, and pigments from plants to print photographs and generate positive sun-prints. Chlorophyll printing uses photosynthesis as a photographic process to print images on leaves, while chemigrams are created by forcing a chemical reaction between photographic paper and a resist—typically a form of varnish or liquid i.e. oil, honey, sugar, etc.—and utilizing traditional darkroom chemistry to create an experimental visual result.

I have always loved chemistry as a science, and I find that experimental photography blends the thrill of that with the care of image-making seamlessly. I also appreciate how tactile and versatile it makes the experience of viewing a photograph, an act that is more sensorial than just the eyes.

Through this experimentation, I teach and have seen how experimental photography allows anybody to be a photographer and author of their stories by using repurposed items in a kitchen, the sun as a catalyst for printing, and the body as a tool.

Nowadays, I’m enjoying the messiness and thrill of the unexpected that comes with experimental photography. It’s definitely a controlled chaos. I’m a self-professed “slow shooter” so being able to be mindfully present when pre-treating fabric with these chemical recipes, and creating works that pull from the land to process and create, soothes my soul and body from feeling overstimulated by the demands of this world.

Isabella Marie Garcia teaching during Spring 2024 at Girl Power Overtown as the ICA Narratives 2023-2024 Teaching Artist. Image by and courtesy of Chris Carter.

Elizabeth Ransom: What impact have you found providing access to alternative photographic processes has had on these communities?

Isabella Marie Garcia: In providing access to alternative photographic processes to these communities, I’ve seen how their ideas of art-making and photography are expanded altogether. Many of the students I worked with are artists that work with drawing, painting, graffiti, etc. but in showing them a means to make images outside of an iPhone or traditional camera, they were given the opportunity to learn about new possibilities within the medium.

The students were often hesitant at the start of each class regarding why these alternative photography techniques were valid ways in which to explore externally what they had internally gone through, and were actively processing. I saw hesitance turn into an active interest to finish what they had started, culminating in the last class where we asked them: what makes you feel uprooted? The answers to that question were reflective of the work produced by students, of situational and circumstantial displacement, along with an interest in honoring through permanence the life and people they missed from living for an extended period of time in the facilities.

It’s important to enter these spaces absolved of a savior complex. The hour-long classes I taught with my students were not because I was there to fix them or change their lives. I’m not there to pry about why they entered these facilities in the first place or ask for personal information. Rather, it was a time in their day to take a break from what they were experiencing and focus on an activity where they could use their hands in creating work reflective of themselves as they wish to be seen.

Specifically in the residential rehab and juvenile detention I taught within, the need for creative stimuli is well-received by the students, especially as they are regimented by the routine and schedules ordered by the facilities. The time you eat is organized for you, when and in what order you take showers, how you enter and leave physical spaces is always supervised.

The teaching itself can be very insular, but through a research fellowship I was awarded in 2024 through Women Photographers International Archive (WOPHA), I was able to take the time and mental focus into looking outside of my personal experiences into the work of others in Miami, nationally across the United States, and globally around the world. It also helped contextualize this work at different periods of time, from the 1970s into the 1990s and contemporary moments today, and permitted me to think more critically about arts education, the weight of mass incarceration in the American South, and carceral abolition as pillars of this work.

I believe in prison abolition and through implementing arts education within carceral systems, there’s a humanization of the dehumanized unlike no other. Each individual that enters and operates in these systems as “insiders” or “outsiders” innately holds a power, one that is either censored or enacting the censorship of an individual’s agency. As art educators, particularly photographers in the context of this research, this dual fight of censorship is broken when incarcerated students are liberated to speak their wishes, vocalize their truths, and portray their histories through lens-based mediums, and those adjacent. This is not to say that all arts educators and photographers teaching in carceral systems are abolitionists. Rather, it is to say that the work is inherently equal to wanting a world where these facilities are obsolete, incapable of serving any sentencing in an alternative future.

I am thrilled to share that I’ve been awarded a grant under the same name of the research, The Photography Care Matrix, that will run a year-long workshop program teaching experimental photography within correctional facilities in Miami-Dade County. I can’t reveal all the details of the grant until further notice, but am feeling very supported and eager to continue this work within Miami.

Installation View of UPROOTED, Curated Student Exhibition for ICA Narratives by Isabella Marie Garcia and Jessica Helsinger at Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, Miami, Florida. Image by and courtesy of Chris Carter.

Elizabeth Ransom: How did you navigate any ethical implications of working with folks in juvenile correctional facilities and residential rehabs, particularly in relation to representation, agency, and ownership over their creative process?

Isabella Marie Garcia: This is an essential question to consider when entering carceral systems, especially because you are working with a larger web of control and surveillance. When working with students in the juvenile justice system, the biggest factor to consider is how anonymity factors into their creative process. Their identities must remain anonymous, so does this agency remain absent as a result of the state’s control?

The Critical Carceral Visualities initiative at the University of Michigan is tackling this argument through the term “facelessness,” coined by scholar Ruby C. Tapia1 (1). They state, “We know that photographers are not allowed to capture the likeness of incarcerated youth. Given this context, we consider ‘facelessness’ as an act of resistance deployed by the agential subject whose non-appearance rejects reformist narratives of individual and exceptional suffering. […] abolitionists turn away from the trap of individuation that is so deeply embedded in the tradition of portrait photograph and indeed the larger genre of prison photography, while granting the agential import and critical sensibilities, questions, and political incitements that recognition of individuals affected by the carceral state can inspire”(2).

In the more expanded realm of experimental photography, I would like to argue that the reality of “facelessness” is shattered altogether for a greater alternative vision, one entirely removed of realist portrayals. Rather, they allow the experiential art-making to rest in the maker’s hands and the beauty of chance. For the incarcerated youth I worked with during the course of a year, I can recall their desires for beauty routines of the everyday, of wanting to braid and do each other’s hair, craving the normalcy of external appearance that is extremely restricted and reduced within the juvenile detention and residential rehab. There’s an empathy necessary to hear them out on not wanting to be photographed when they are not at their best—emotionally, mentally, and physically. Instead, the lens-based medium of experimental photography posits a framework in which to extract identity as interpretative, abstract, and lucky.

There’s also the reality of how gendered these systems are, and being able to express queerness, transness, and self-identification in their work was vital. I had students placed in a pod of their birth gender and called by their dead names but that identified as non-binary or trans. Through the experimental photography, they were able to reclaim that agency for their chosen identities and names through their work.

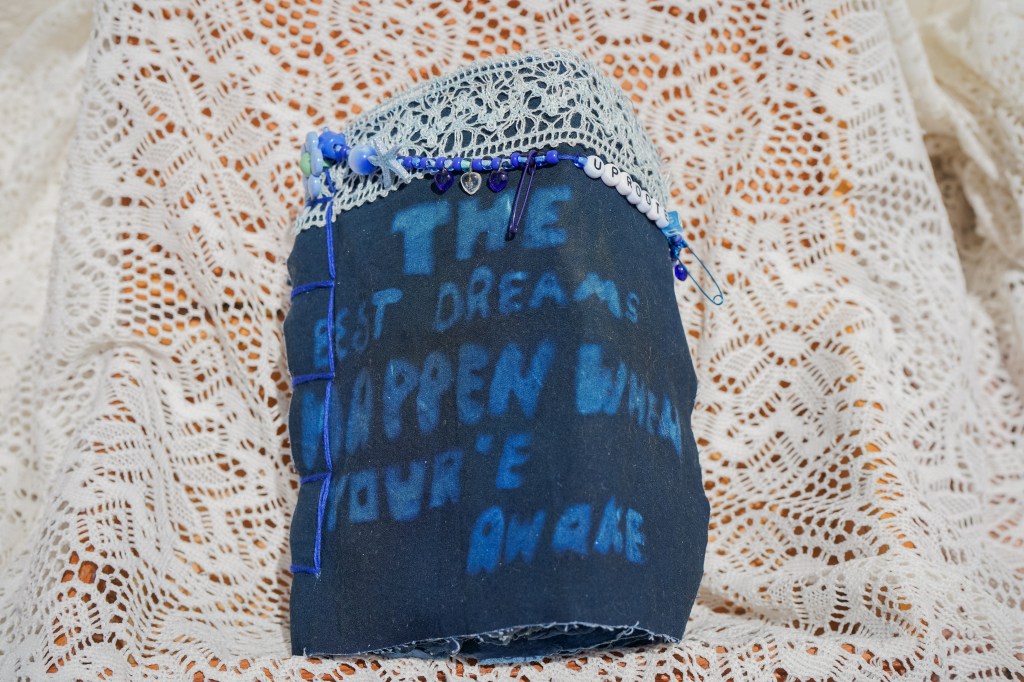

Isabella Marie Garcia, UPROOTED, 2023-2024, hand-bound artist book with Japanese stab bookbinding, handmade paper made out of cyanotype blankets and artworks that were unable to be returned to students, printed, cut, and collaged film photographs on glossy photo paper, pen on handmade paper, embroidery thread, beads, and singular cyanotype cotton artwork as the soft cover, 7 x 5 x 4 1/2 inches. Image by and courtesy of Isabella Marie Garcia.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your book UPROOTED (2023-2024), you repurpose cyanotypes created by students who participated in your workshops into pulp that is then turned into handmade paper. You then incorporate film photography documenting your time teaching as well as the addition of beadwork. Can you speak to the elements of joy and playfulness that are embedded within this work? And can you tell us about some of the processes involved in the creation of this piece?

Isabella Marie Garcia: Joy and playfulness are elements that I’m always conscious of including and calling to in my practice, especially as I explore sites of pain consistently through my work, from grief and death to alternative experiences with burial, cremation, and arts education in carceral systems. I want to make sure to keep this balance in work that can be heavy to emotionally deal with, and I’m always thinking of symbology that I really am drawn to that centers on humor, such as playing card imagery, jokers, and jesters. The term in Spanish I think of with this payasa, which literally means clown, and is reminiscent of being raised as a first-generation daughter in a Cuban household. I was raised by my maternal grandparents while my parents worked full-time jobs in broadcast news, and humor became a big part of my life early on through those who contributed to my upbringing.

This balance of celebrating and grieving were moments I experienced during my teaching. I’d leave these sites meeting students that expressed deeply personal situations and moments in their lives, and I learned to debrief with my team on how it emotionally weighed to hear those experiences. It made me appreciate the value of keeping my personal life light and having fun where I can to make sure I was in the right headspace to return to these facilities and bring joy to my students where I could.

Last April 2024, I was accepted into the O, Paper Mill fellowship— a fellowship program at Miami Paper and Printing Museum that gave four fellows experience planning and executing public workshops, introducing them to the process of organizing a project for O, Miami while they learn high-level papermaking and bookbinding skills. As part of my ICA Narratives teaching in Summer 2024, I taught my students papermaking and bookbinding so they could create a journal from scratch over the course of four weeks.

At the end of my teaching at these sites, I’d often return to students who expressed that their artworks were disregarded or thrown away, or in the case of students that were in and out of these facilities, unable to be properly returned since they could be there for a week at a time, or months on end. As a result of this, at the end of my teaching year, I was left with cyanotype fabric artworks that I decided to repurpose into handmade paper and bind the handmade paper into a photobook that I titled the same as my teaching curriculum and student exhibition—UPROOTED.

Using a Hollander beater that is available at Miami Paper and Printing Museum, I cut the fabric into small 1-inch squares, which is then beaten down into pulp using water and blades within the beater. After the pulp is fine enough, I drain it of all the water and store it in a five-gallon bucket that can be utilized for papermaking at any point. To make the handmade paper, I pour cups of the pulp into a box filled with water I repurposed into a station, used 5 x 7 inch mould and deckles to sift the pulp out, and then placed the sifted paper on pellon sheets that can be placed on clean windows to dry overnight. It typically takes a day or two to fully dry, and then the paper can be peeled off, windows can be cleaned with Windex, and the handmade paper is ready for binding.

The specific binding I used for this book was Japanese stab-stitch binding, and this is because it’s an easier binding to incorporate the amount of pages I had selected for the book, and for the thickness to be seen from the spine. The front cover is a selected small-scale cyanotype on artwork by a former student that I felt encapsulated the importance of being present in these spaces and facilities. I decided to incorporate my own film photography and handwritten journal reflections from the September 2023 to September 2024 teaching year as a way to visually inform what my personal life and mind was passing through in between these educational moments.

The Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) is just one of the sites I worked with during the past spring and this summer, which has decided to not renew state-based contracts with organizations like AMIKids that permit youth leaving incarceration to benefit from intervention programs that include visual arts instruction. This is resulting in the closure of AMIKids’ Florida-based locations and the loss of jobs across these locations, such as Key Biscayne where I spent eight weeks teaching experimental photography to the cohort of students present at the time.

My last footsteps at the location were celebratory, as three of my students were graduating with the program in order to continue their education by enrolling in technical programs and GED diploma classes. The joy of their graduation was marred by the liquidation of the location’s equipment and on-site supplies, where everything from scuba diving equipment to office chairs was being cleared before the site’s impending closure. One of the items they gave me from the location was HP photo paper, which I decided to print on with my inkjet printer in my home studio and place scrapbook-style into the photobook.

My students were often having fun where they could, and during a class in the summer that I dedicated to making beaded bookmarks for the handbound books, the students I was with that day turned to making friendship bracelets for each other. I made the clasp of the UPROOTED photobook out of beads that called to this moment, that spells the title, and that is reminiscent of the blue of cyanotypes and Miami as a landscape for this teaching, in the shape of starfish, hearts, clothespins, and flowers. It’s a tribute to the earliest art-making I made as a kid, and the art-making made in these spaces with my students, which was hardly steeped in perfection and centered in the delight of the moment that arrives when given the access and space to create. That’s all I’m there to do: facilitate joy.

For more information about Isabella Marie Garcia and her practice please visit her website HERE

You can also watch Isabella Marie Garcia speak about her work during the WOPHA 2024 Congress on YouTube.

A cyanotype on cotton blanket artwork created by a Citrus Health Pembroke Pines student during the ICA Narratives 2023-2024 program. Image by and courtesy of Isabella Marie Garcia.

Footnotes:

- 1. Critical Carceral Visualities Team, “Images of Detained Youth Through an Abolitionist Lens,” ArcGIS StoryMaps, August 8, 2024, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/4150907390da4038b77ed37d8b44ae3c.

- 2. Ibid.

Leave a comment