27 March 2025

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

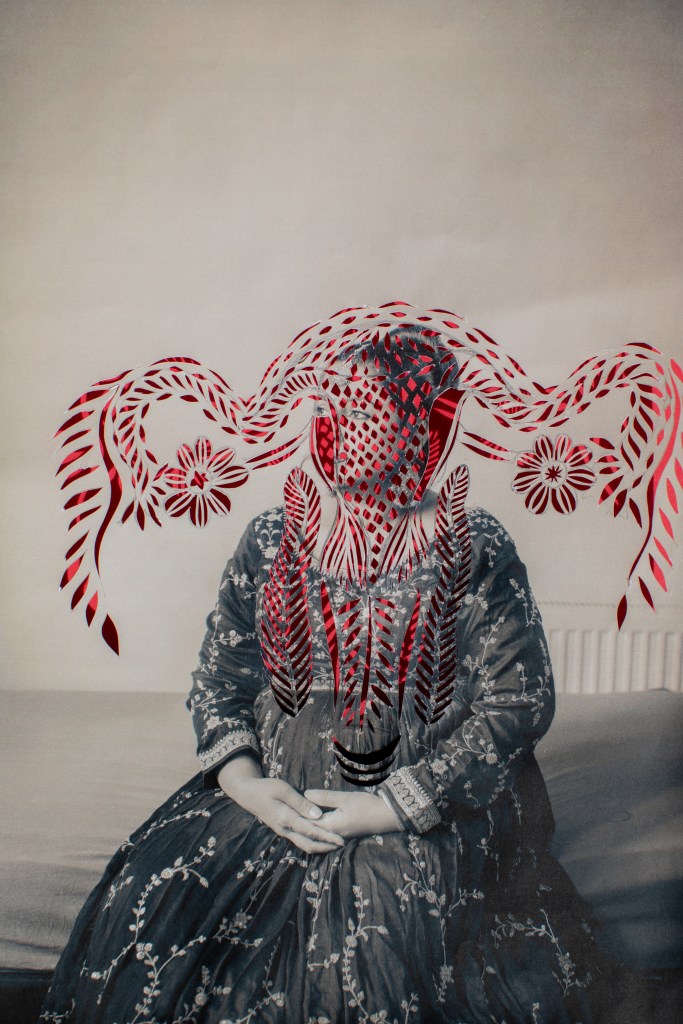

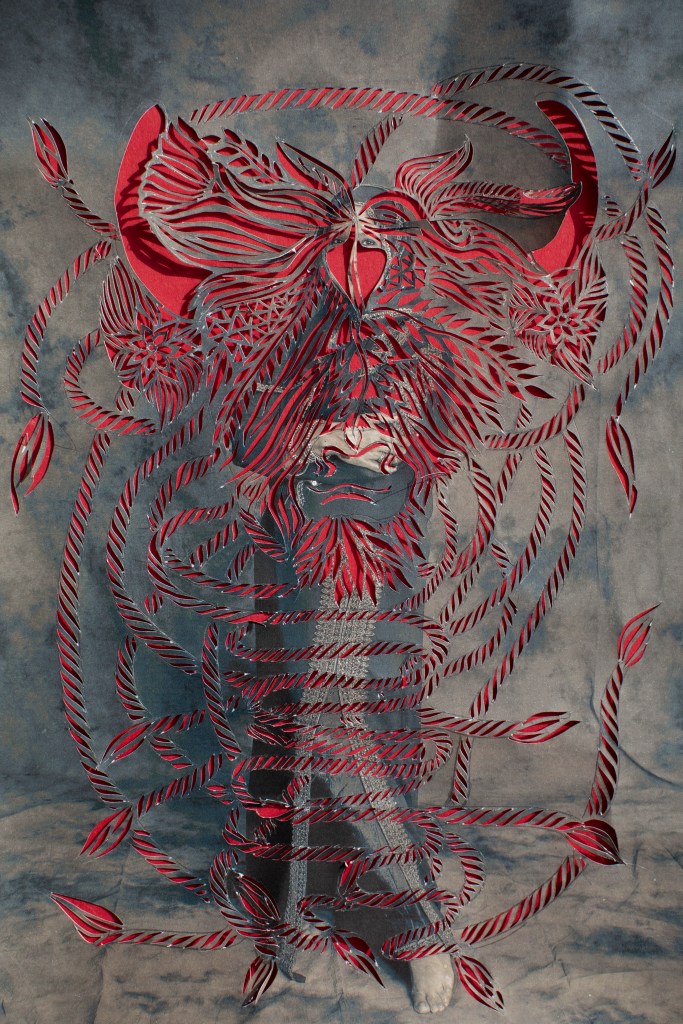

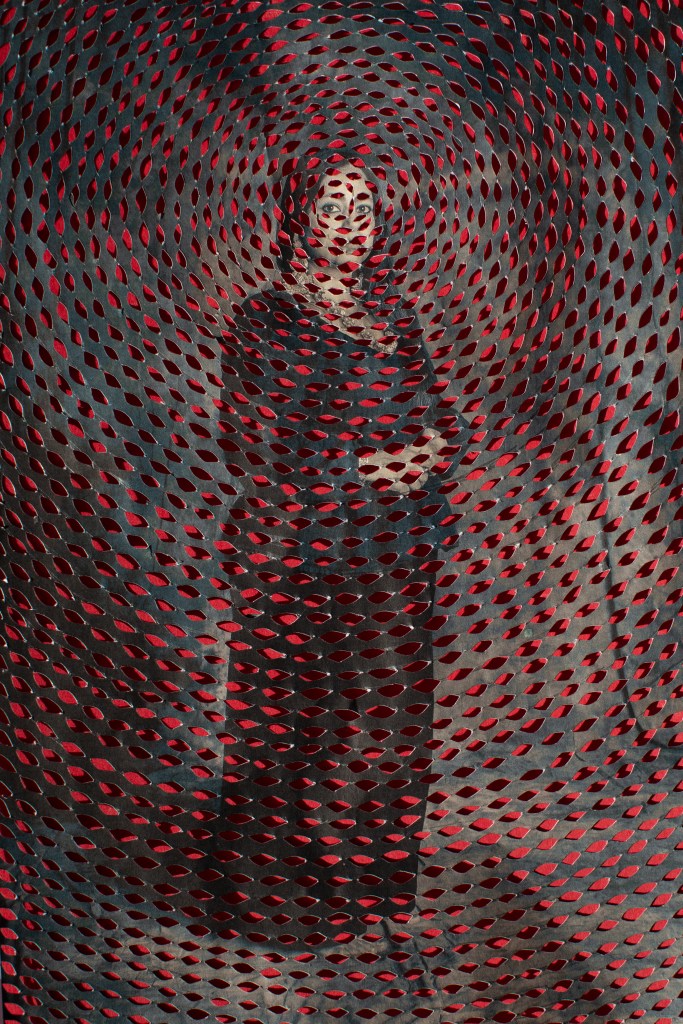

In her body of work A Thousand Cuts Sujata Setia examines patterns of domestic abuse within South Asian communities. This powerful body of work employs the South Asian art of paper cutting, known as Sanghi Art, to slice into the surface of photographs depicting victims of domestic abuse. This unique mark making technique results in striking images that reveal a bold red colour beneath. Sujata provides a space of healing, empowering victims to share their stories.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series A Thousand Cuts you explore themes of domestic abuse in the South Asian Community. Could you tell us a little bit about the inspiration behind this body of work?

Sujata Setia: Derived from the ancient Asian form of torture—Lingchi, or “Death by a Thousand Cuts”—this project examines patterns of domestic abuse within the South Asian community.

I use the metaphor of Lingchi to explore the cyclical nature of abuse and its trans-generational mental and physical health impact. Each survivor’s portrait is printed on fragile A4 paper, symbolising the precariousness of her existence. I then create incisions on the image, reflecting the slow, systematic erosion of self that abuse inflicts. The red beneath these cuts represents both suffering and resilience—the pain of lived trauma and the possibility of renewal.

The project is intentionally domestic in scale, utilising household materials to reflect violence occurring within intimate spaces. The final works are photographed in a tightly cropped frame to evoke suffocation and the absence of escape.

By visualising the psychological fragmentation caused by domestic abuse, this work underscores the mental health consequences of trauma—its impact on identity, self- worth, and the long-term emotional toll on not just survivors but their future generations as well.

“अतीत का भविष्य” (Makings of past)

Elizabeth Ransom: You use a unique mark making technique by slicing the surface of the photographic print to reveal a vibrant red colour beneath. Could you tell us about this process and why you chose to work with this specific approach to image making?

Sujata Setia: As a portrait photographer specialising in capturing people’s faces and expressions, I was faced with the challenge of protecting my sitters’ identity here and yet create both a means for a dialogue between the narrators and the wider public and also an aesthetic experience.

The first attempt that I made is on my website. It’s called “Main Mukkamal – I am enough” But I felt very uncomfortable with that work. It was entirely me and my personal artistic tools including image-making and poetry. I was wielding power. I needed course corrections. So I went back to the drawing board and listened to their testimonies over and over again. And each one of them said to me in their own words that “I am torn to pieces from inside.”

That became my starting point. I then drew inspiration from the metaphor “Death by a thousand cuts” and the South Asian art of paper cutting called – Sanghi Art (historically this art was created by Hindu god Krishna’s female consorts to draw his attention, showcasing an inherent power structure between genders,) to create these contemplations of not just abusive lived experiences but also an inquiry into culture.

Another reason for making cuts was that as a survivor myself, I wanted to

understand what is in it for the perpetrator? In the literal act of making cuts and thus destroying the prints, I also embodied the persona of the perpetrator within me. That helped me understand the perpetrators’

obsession with violence and destruction. There is rhythm in violence. A form of meditation even.

“मेरी हद्द” (The premise of my existence)

Elizabeth Ransom: Can you tell us about your connection to Shewise UK, who they are, and what role they played within this body of work?

Sujata Setia: Sayeeda Ashraf, who is the cofounder of Shewise UK, was my work colleague in the past. It was almost divine timing that, when I started to think about working on this project and was looking for potential charities to collaborate with, I came across Sayeeda’s work in the domain of domestic abuse via a LinkedIn post.

And so I reached out to her and spoke with her very honestly about the fact that I was not really sure of where I am going with this. But I need her and Shewise UK’s support. Sayeeda along with Salma Ullah and Saima Khan from Shewise, have been extremely instrumental in helping me reach out to the survivors and initiate a dialogue that is ongoing of course but is most importantly sheltered with appropriate safeguards.

“अल्ला कि गाँए” (God’s Cow)

Elizabeth Ransom: What was the experience of meeting with this community like for you and the survivors on an emotional level? Did you find it challenging or was it a cathartic process? How did you ensure that the participants felt safe and empowered?

Sujata Setia: The creation of these images took place in a meeting room in Hounslow, where I met with survivors of domestic abuse. Within this space, we engaged in deeply personal conversations, sharing lived experiences and revealing the realities of abuse. It was not a formal interview but an open dialogue—an act of trust and solidarity.

As a survivor myself, I’ve often struggled with confidence in my own voice. Yet, I felt that the only way I could attempt to break the cycle of abuse as an artist was by honouring the stories of survivors through this work. When I reconnected with them, it felt like step one all over again. I had to be honest and tell them, “I don’t know where this will lead, but let’s just sit together and talk.” There were no expectations—just a shared space where we could hold hands and listen to one another.

The survivors have been incredibly generous, giving their time and trust. Some were willing to revisit the process multiple times, allowing me to refine the vision until we felt it was right. Others came through the door, shared their story, and never returned. Each person’s journey was different, and that choice—the freedom to participate on their own terms—was essential.

Consent, agency, and emotional safety were at the core of this work. Every survivor had full autonomy—whether to share their story, take part in the photography, or simply be present in the space. From the start, I worked with SHEWISE to ensure that caseworkers were always available. I am not a mental health expert, nor am I equipped to navigate the individual legal or emotional complexities each survivor faced. Many were in the midst of court cases or dealing with the impact of abuse on their children. Having professional support in the room meant there was always someone to step in if the process became too overwhelming, ensuring that everyone’s well-being came first.

Ultimately, I believe there is healing in conversation. Simply being able to sit together, without pressure or interrogation, allowed these women to share at their own pace. This was not about extracting stories but about creating a space where trauma, resilience, and hope could exist side by side.

“मिट्टी के दायरे” (Circles in Sand)

Elizabeth Ransom: Within this body of work, you explore concepts such as trauma, suffering, genetic and cultural predispositions, gender and identity politics. In terms of raising awareness and supporting survivors of domestic abuse what impact has this project already had and how do you envision the effects of this project on communities of survivors going forward?

Sujata Setia: This project has already begun fostering critical conversations around domestic abuse, not just within survivor communities but also in broader public and artistic spaces. Many survivors who engaged with the work have expressed that the process itself—being seen, heard, and having agency over their narratives – was a form of healing. For some, it was the first time they shared their story in a space free of judgment or fear.

Beyond the personal impact, A Thousand Cuts has helped bring these narratives into public discourse, creating a visual and emotional language that resonates beyond statistics and legal frameworks. It has been showcased in exhibitions, discussions, and community spaces where audiences—many of whom may have never encountered these realities so intimately—are compelled to reflect on the systemic nature of abuse.

Going forward, I hope this work continues to act as both a mirror and a bridge: a mirror for survivors, affirming that their experiences matter and are acknowledged, and a bridge for the wider public to engage with these issues through empathy rather than spectacle. I also envision further collaborations with advocacy organisations, mental health professionals, and legal experts to integrate the project into survivor support networks, using art not just for awareness but as a tool for dialogue and recovery.

At its core, A Thousand Cuts is an invitation – to listen, to understand, and to break the cycles of silence that allow abuse to persist.

For more information about Sujata Setia and her practice please visit her website HERE

“कै़द-ए-क़फ़स ” (Prisoner of the prison)

Leave a comment