3 January 2025

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Julia Bradshaw’s images are imbedded with references to topographical maps of the moon, and photographs from the Hubble Space Telescope. Handwritten annotations and technical markings lead you to believe you are glimpsing at galaxies far away; however, upon closer inspection you will find the reality to be much different. Bradshaw’s extensive research and playful use of photography invites audiences to use their imagination and consider the line between truth and fiction.

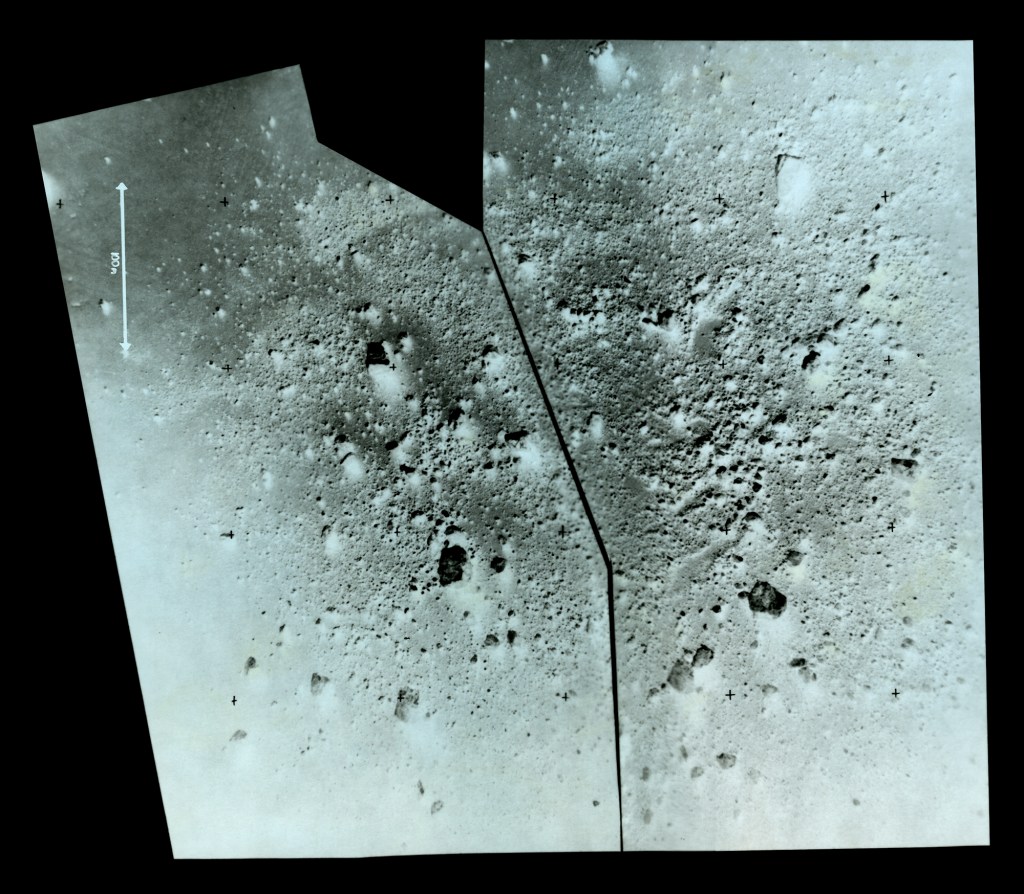

Lunar Sample Collection Site, 15″ x 13″, Silver gelatin photograph with dye, 2019-2021

Elizabeth Ransom: In your body of work Survey you reference astrophotography and the history of topographical images. Could you tell us a little bit about what inspired this project and the research that went behind making this work?

Julia Bradshaw: This project stems from a culmination of experience, observations, and a deep dive into an unanticipated subject; all this percolated together to form the creative inspiration. In August 2017 a solar eclipse was visible in Corvallis, Oregon. Starting in late 2016 (and once I got over the shock that no one initially thought to include the art department in the preparations for this event), I led a number of art and science initiatives associated with the eclipse on the Oregon State University campus. This resulted in nine workshops to teach people how to build solar filters and photograph the sun, about ten community arts events during the eclipse weekend, and I curated the exhibition Totality in the University art gallery by including artists who reference our cosmos in some way. Along the way, I researched photography’s early contributions to science (photography of the 1919 eclipse helped prove Einstein’s theory of relativity) and the importance of photography in planning and communicating the Apollo and Surveyor lunar missions. I also read early theories of space exploration and noticed how florid and, occasionally, speculative nineteenth century scientific writing is in comparison with the more objective scientific writing of today. For example, the introduction to the report of The 1900 Solar Eclipse Expedition by the Smithsonian Institute reads more as a competitive adventure tale than my layman’s impression of a scientific expedition. Visually, I was enjoying the photographs of early astrophotography as well; with their technical flaws, annotations, and their importance as data. For example, Hubble’s 1923 photograph of Andromeda, which proved there were galaxies beyond our own, is not only scientifically important, it is a stunning visual object with its glass plate flaws and handwritten annotations. To be honest, I considered this research as extra-curricular, as part of my Sunday reading not attached to my role as a professor of art and not part of my creative research at the time. I was allowing my curiosity to guide me. I did not anticipate it would become the basis of a new photographic exploration of my own.

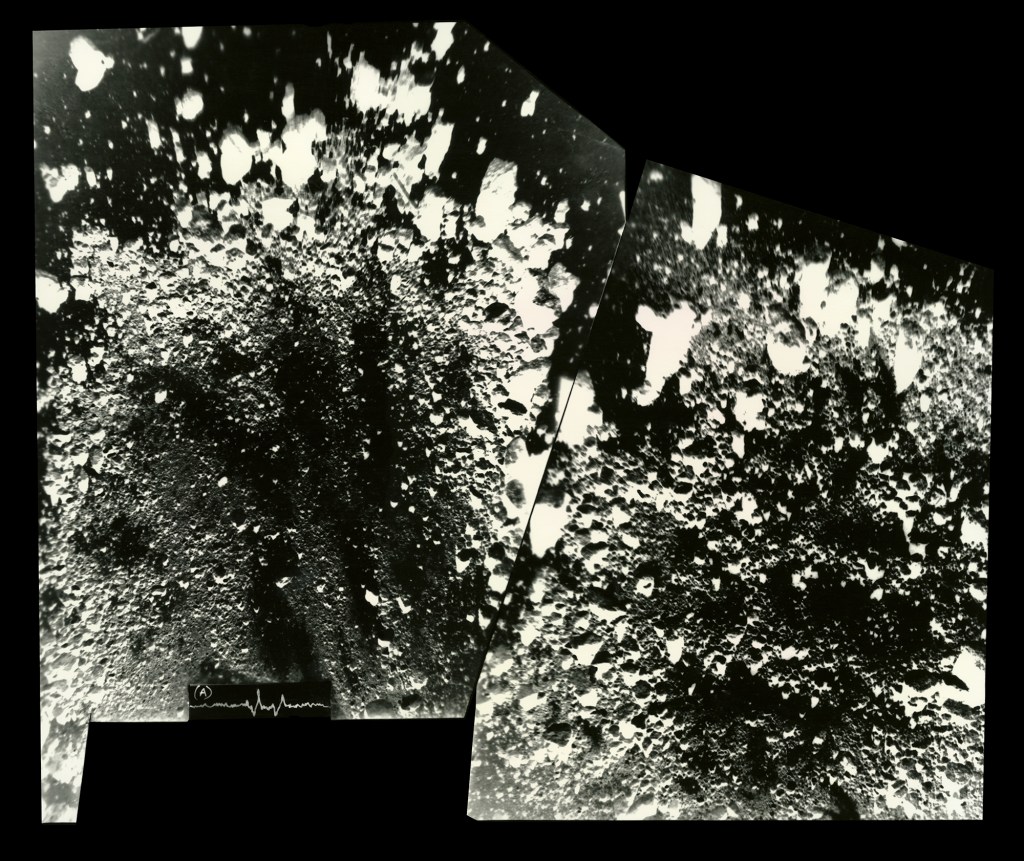

Traverse from LM to Station, 13 12″ x 19″, Silver gelatin photograph with dye,

2019-2021

Elizabeth Ransom: The final rendered images in Survey are fictional, yet they appear to be realistic topographical photographs of planets in space. This body of work uses the aesthetics of scientific imagery and symbols to turn photographs of dust and surface textures into imagined scientific worlds. Can you tell us a little bit about the mixture of reality and fiction in this work?

Julia Bradshaw: The slippage between truth and fiction in photography has interested me for a while (pre-AI, which is a whole different discussion). My personal observation is that most people (unless primed) are predisposed to take photographs at face-value and that they are not trained in close observation. The readers of this website will know that images have been manipulated since the early days of photography’s invention. Since 2012, some images in my projects have been extensively digitally manipulated but they present themselves as true observational photographs, rather in the way Andreas Gursky created composite images in the 1990’s (i.e. before his more recent obvious manipulated images). It tickles me, when my photographs are accepted as a true representation; but I am really striving for the subtle impossibility of the photographs to raise a question in the observer. At this point, they become observationally-sticky; and my ego likes it when someone pauses to look at one of my pictures longer than most. Despite this, my purpose is not trickery, rather to make visually compelling images and to add to my personal dataset of observations about photography. After all, the images are all real to me. They reflect my imagination.

With the “Survey” project, unlike previous projects, all the images are fictional representations of imagined lunar or cosmic explorations. In the exhibition setting, I don’t overtly say that these are imagined landscapes. I let the viewer come to that conclusion (and some don’t). But it takes a while, as the default position is that a photographic exhibition, particularly one using silver-gelatin paper, is generally a representation of the truth.

The 1874 book The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite by James Nasmyth and James Carpenter, was a stimulus. In 2017, I read a headline on a clickbait-website screaming that Nasmyth’s photographs were the first fake photographs of the moon. I took umbrage with that as Nasmyth and Carpenter describe in the preface to their book the method of scientific illustration they used. This consisted of plaster models, which they created with reference to meticulous hand-drawn telescope observations of the moon’s surface as their guide. These were then photographed in the sun to create the “lunar effects of light and shadow”. In some mysterious way, their photographic scientific-illustrations gave me permission to create my imaginations.

GRB 130472DA, 18″ x 15″, Silver gelatin photograph with dye, 2019-2021

Elizabeth Ransom: This project was created using a pinhole camera and traditional darkroom techniques. Can you walk us through the creative process behind making this work?

Julia Bradshaw: I said at the beginning of this interview, that this project was a culmination of experiences and observations. As a teacher, I have taught the pinhole camera to beginners for almost two decades. In demonstrating the process, I would often point the pinhole-oatmeal-container-camera so that there was concrete texture in the image. For some reason, I was strangely attracted to the look of the concrete in the resulting-images. I would often mutter to the students that “I really like the look of concrete when photographed with a pinhole camera”. It only took me 15 years to take this observation and actually use it in a project – duh!

All the photographs are images of a concrete floor, the cracks and divots in that floor, with the occasional addition of grit and gravel. I used an 11”x14” pinhole camera I constructed out of cardboard with photographic paper as my recording mechanism. The initial photographs were all taken when I was a resident at Djerassi Resident Artist Program in California and where I was supported by a grant from the Ford Family Foundation in Oregon.

With pinhole images, using light-sensitive (silver-gelatin) paper as the recording mechanism, the resultant image has more contrast than in a typical film/camera process. This can be mitigated by using a yellow filter with the pinhole-camera, which I did not do with this project. Then, the initial developed image is an inverse or negative image. I also was dependent upon the sunlight for the images and the exposure times were between ten minutes and three hours. This resulted in a confusion of lighting effects – imagine a shadow recorded over three hours.

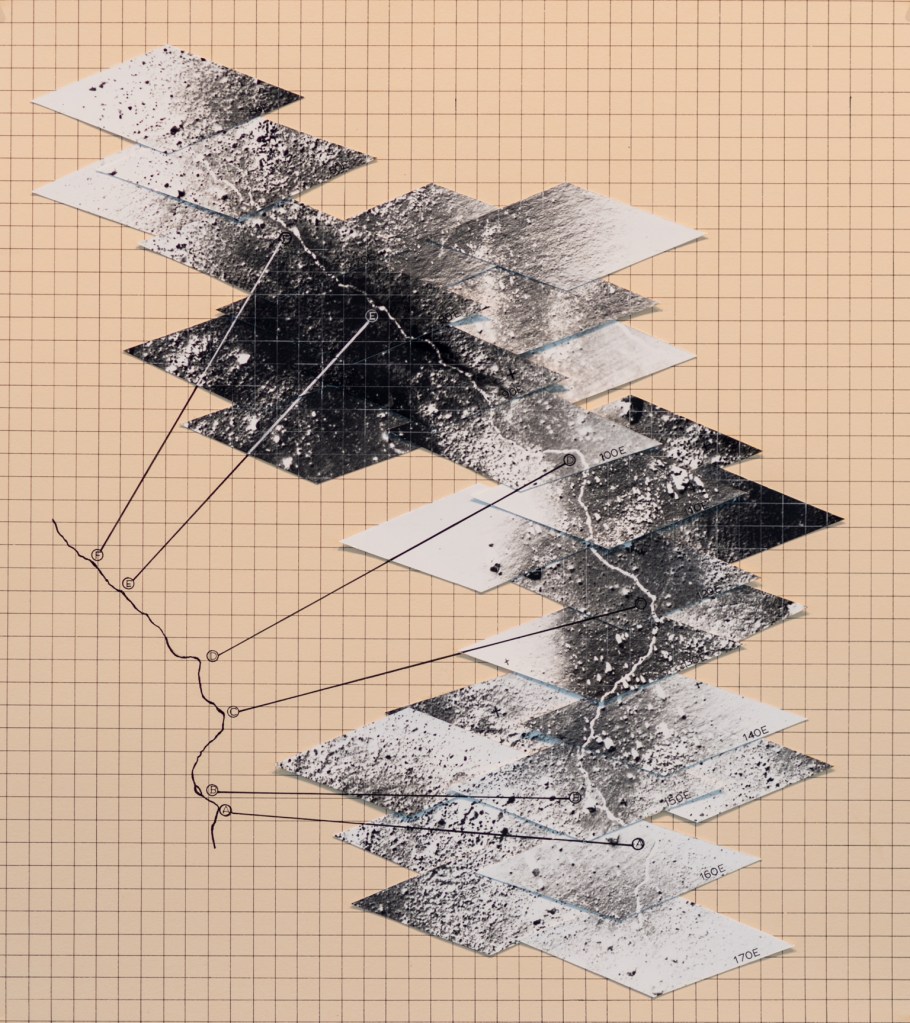

The increased contrast, together with the negative image, and the exceedingly long exposure-times leads to the other-worldly aspect to the images. These initial images were then further manipulated by contact printing the images in the darkroom to create a positive, then adding text, arrows, and other annotations with a technical pen. Most images were then contact printed again. Often I changed the shape of the image by joining two images together and, because the NASA images retain all data, the images are not necessarily rectangular. I also dyed them, because I like dyed silver-gelatin images – a 1970’s throw-back.

Nutumcrudendustrum, 15″ x 22″, Silver gelatin photographs with dye, ink, on paper, 2019-2021

Elizabeth Ransom: Within this work you manipulate the surface of the print using a knife, pen, dye, joins, and reversals. These techniques aid in the illusion of scientific imagery that you are creating. Can you discuss the role of imagination and play in this body of work and what methods you use.

Julia Bradshaw: Because I was so steeped in early nineteenth century astrophotography, early cosmic exploration theories, and images from the 1960’s NASA expeditions, it was easy and fun to make the sly scientific references on the images. In viewing early scientific photographs, I delighted in the hand-written annotations with their cryptic codes (to the layman) and the over-abundance of arrows. I also enjoyed reading pre-Surveyor theories of what features might be on the moon – such as speculating that a feature that looked like a lava tube might be a possible refuge for astronauts. In addition, I learned how and why the Surveyor photomosaic images were made and this inspired another set of images. For images such as Sinuous Rille 170E, I found that it was very relaxing to make the text and the cuts by hand, in daylight and outside of the computer. Each was quite laborious to make. In making the images, I leaned into my informed imagination and my internal playful self to make work that gave me a sly smile. The work was fun and escapist to make.

Finally, the work is deliberately absurd in that it (without impact) imperceptibly mocks the disparity in funding for the arts in comparison to sciences in academic circles. All the images were made using a cardboard container for a camera, with ink and hand-drawn annotations on paper. Clearly, advances in science and engineering require an extraordinary monetary investment; in comparison this project explores the richness of inner head-space.

Sinuous Rille 170E, 16″ x 18″, Silver gelatin photographs with dye, ink, on paper, 2019-2021

Elizabeth Ransom: Survey references space photography, astronomical explorations, and alphanumeric designations. How do you see the relationship between art and science reflected in your work?

Julia Bradshaw: The work is not scientific. I truly admire and study the art of people who make good work based on science and data as I am drawn to art that is compelling and smart. But this work does not meet any scientific standard. Therefore, I choose to say it is informed by science. Science, imagination, and play, those three components together. I think that is worthwhile.

For more information about Julia Bradshaw and her practice please visit her website HERE

Ring Crater, 10″ x 10″, Silver gelatin photograph with dye, 2019-2021

Leave a comment