29 November 2024

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

We exist during a time where camera phones reign supreme. These little devices capture all aspects of our lives from our daily activities to the the places we travel. Our social media is inundated with photos of holidays spent exploring new places and images enhanced with a variety of filters. We see the world through the screens of our phones. But what is the impact of technology on the way humans interact with nature? Artist Sonia Mangiapane explores leisure tourism and our relationship with the natural world in her series Ambient, Aberrant.

Off to the MouNtaiNs, 2020, 90 x 76 cm, analogue c-print (photograph with darkroom intervention)

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series Ambient, Aberrant you bring attention to domesticated landscapes and how humans have tamed and managed the land. What inspired you to create this work?

Sonia Mangiapane: This body of work came about while I was enrolled in Masters studies, which provided a focused space in which I could critique and interrogate what had previously been an intuitive way of working with photography. I had always taken photos while traveling, away from my ‘home’ space, often drawn to the places and spaces that I moved through. But at the time, I didn’t fully understand why.

It also coincided with a renewed interest in the possibilities of photography that sit outside of the camera, as well as access to a colour photographic darkroom. I approach photography as a medium of light-writing, in which use of a camera is optional. For me the photographic darkroom allows for a whole host of possibilities free of the rigid constraints of the camera’s program.

With Ambient, Aberrant rather than simply documenting the places and spaces I moved through, I tried to tap into something less descriptive, and more expressive. I wanted to make work that looks like the feeling of going or being elsewhere.

Nature’s Playground, 2020, 90 x 76 cm, analogue c-print (photograph with darkroom intervention)

Elizabeth Ransom: The process of creating this body of work was laborious and involved many prototypes and testing. You employ the use of optical modifiers such as prisms as well as darkroom interventions to create these unique works of art. Could you tell us about the processes you used to create these abstract landscapes in and outside of the darkroom?

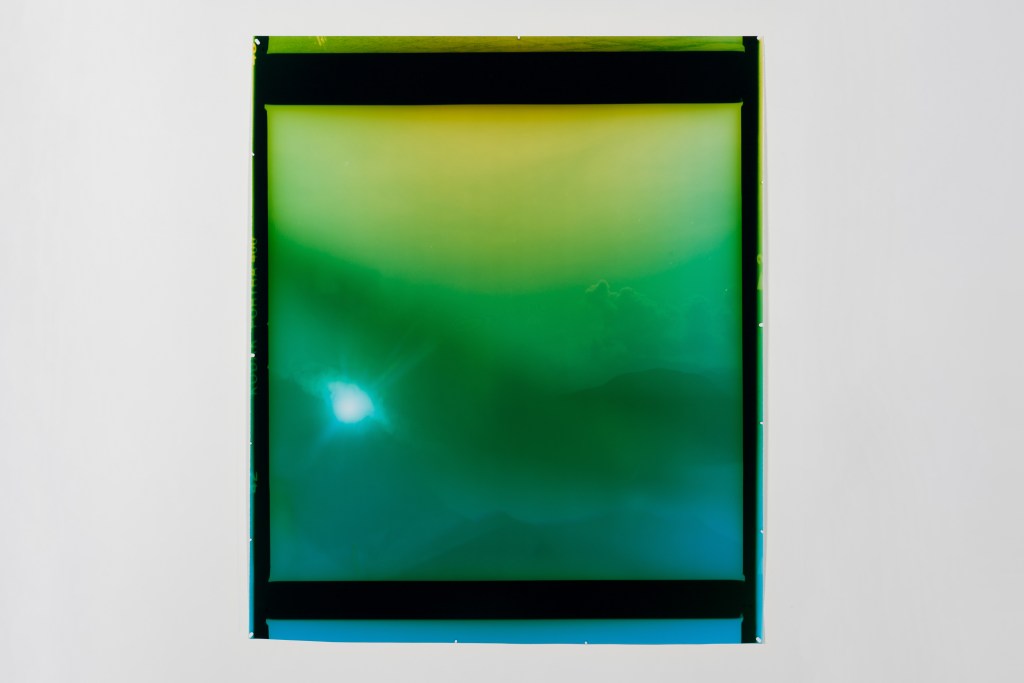

Sonia Mangiapane: When taking photos for Ambient, Aberrant I sometimes placed prisms or other optical modifiers in front of the lens during in-camera exposure; fragmenting, distorting and abstracting the view. I then subjected some images to a second iteration of mediation during print production, through ‘darkroom interventions’—in the colour darkroom during exposure of a negative image onto photosensitive paper I used coloured filters, transmissive objects, light sources or other light modifiers to disrupt the image in some way. This process creates a hybrid image produced partly in-camera and partly in the darkroom.

The process of making is in many ways, the main event of my practice; the resulting artwork merely a remnant of my production process. By approaching photography as a process I believe our terms of engagement with the work changes—photography shifts from a mode of representation towards a mode of performativity. This conceptual framing challenges the photography-as-representation ethos of conventional photographic practices.

top of the hill with minimal exertion, 2020, 90 x 76 cm, analogue c-print (photograph with darkroom intervention)

Elizabeth Ransom: You raise questions about the artifice of sightseeing. Could you share your thoughts on the authenticity of an image and the authenticity of nature and how these themes are explored in this series?

Sonia Mangiapane: My practice sets out from the premise that all photographs are constructions. Despite ample evidence to the contrary, I believe we (still) tend to believe that what we see in a photograph represents some kind of truth. The process of photography—its construction—is thus rendered invisible. In my practice I try to reveal this construction in some way.

While undertaking research for my thesis I came to learn that Western concepts of nature are also culturally constructed; thereby shattering the foundation on which I had built my own ideas of nature. In a way, I felt I’d lost something; yet, when I looked back at my photographs over the years, I intuited it somehow. In my landscape photographs there is often a clue to the human—to the scaping of land—even though human bodies rarely feature in them.

Ambient, Aberrant seeks to simultaneously distil a personal experience of the Romantic sublime and—through a representational ‘disruption’ such as abstraction or cameraless interventions—expose the inauthenticity of the ‘nature’ I situate myself in. The landscape in my work is a symbol of my idea of nature; yet I know it is tamed, domesticated, managed. There is no nature here.

Untitled, 2021, 90 x 76 cm, analogue c-print (photograph with darkroom intervention)

Elizabeth Ransom: Ambient, Aberrant speaks to the relationship of leisure tourism and the natural world. This body of work touches on how we as humans experience places through our phones rather than through our senses. What are your thoughts on the impact of technology on the way we experience the natural world in today’s age of social media and camera phones?

Sonia Mangiapane: Indeed, the history of tourism and photography are inextricably linked. The time around 1840 was

… one of those remarkable moments when the world seems to shift and new patterns of relationships become irreversibly established. … [It] is the moment when the “tourist gaze”,that peculiar combining together of the means of collective travel, the desire for travel and the techniques of photographic reproduction, becomes a core component of western modernity.

–John Urry and Jonas Larsen (2011, p.14)

Today having cameras that fit in our pocket, and connected to the internet for immediate dissemination of our photos, has revolutionised image culture. We take more photos than ever before, and they circulate through the network like never before. Even though our instinct is to document (ourselves in) a place through the act of photography, I believe we run the risk of missing out on a more holistic experience.

But before photography itself there were other technologies which served a similar function. The Claude Mirror is one example: a pre-photographic optical device used by artists and tourists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to frame and simplify the visual qualities of the landscape. It took the form of a pocket-sized oval- or rectangular-shaped black-tinted convex mirror, sometimes enclosed in a fold-out case.

To use the Claude Mirror one turned their back on the vista, viewing its reflection in the instrument. The mirror’s convex shape compressed the landscape and its black surface softened and simplified the scene—fine details were lost, tonal ranges limited; an effect mimicked in a smartphone screen’s reflection with the display off. The similarities to moderntechnologies don’t stop there; Jen Rose Smith (2017) and Robert Willim (2013), for example, liken the Claude Mirror to social media platforms like Instagram which filter and mediate reality in a similar way.

The Claude Mirror, like the camera phone itself, can be viewed as a metaphor for the artifice of sightseeing. The unthinking, unengaged tourist observes vistas or sites mediated through an apparatus (camera) or constructed cultural idea; visiting a place just to ‘see’ it, taking a family snapshot or selfie for posterity, and moving on. The image from the camera, or Claude Mirror alike, becomes the memory; bypassing the embodied experience of actually being there. What matters most is the image, not the moment.

How would our experiences change if we didn’t take that photo?

Untitled, 2022, 90 x 76 cm, analogue c-print (photograph with darkroom intervention)

Elizabeth Ransom: How has working on Ambient, Aberrant changed your own perception of nature and photography?

Sonia Mangiapane: It has made me more aware and mindful that my own relationship to Nature is moulded by my particular cultural, political, social and economic circumstances. I am an Australian who has lived in the Netherlands for the last twelve years, who travels occasionally to the European alps as a tourist. In Australia the natural world is wilder; continuous mobile phone reception off the beaten track is rare, there are poisonous snakes to worry about. In stark contrast, in the Netherlands there is barely any part of the landscape that has not been manipulated. The Dutch have reclaimed, diverted, dammed land and water to submit to their own demands for centuries. So I travel to the European alps to satisfy my cravings for wilder places. But I learnt that those places weren’t as wild as I might have imagined.

These days I tend to think twice before taking a photo, or even bringing my camera along with me when travelling to wilder places (which post-pandemic I haven’t done nearly as much as I would like!) It has made me very interested in learning more about how humans’ perception of nature has changed over the centuries.

I’ve also come to realise that although I am quite critical of the constructed aspect of the Natural world, that without those human interventions, land management practices and roads I would not have access to these places…and for that I am grateful. That I can experience such places of wonder at all is something I no longer take for granted.

For more information about Sonia Mangiapane and her practice please visit her website HERE

Placema(r)ker, 2021, 90 x 76 cm, analogue c-print (reversal contact print with darkroom intervention)

Reference list

Smith, J.R., 2017. The 18th-century phenomenon of putting afilter on a sunset for likes. [online] Available at: <https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/claude-glass>

Urry, J. and Larsen, J., 2011. The tourist gaze 3.0. 3rd ed. Los Angeles ; London: SAGE.

Willim, R., 2013, Enhancement or distortion? from the Claude glass to Instagram. In: EC Sarai Reader 09, ed., Sarai Reader09: Projections, pp.353–359

Leave a comment