25 October 2024

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Throughout the US some chicken plants and other agricultural organizations are dumping waste materials that are rich in nitrogen and phosphorus directly into nearby waterways. This causes the degradation of local ecosystems. Motivated by the negative environmental impact on these vulnerable environments, American artist Kari Varner creates images of these locations using a unique process of growing algae. Each image can take up to a week to emerge and involves a great deal of care and labor to create. Kari hopes that by drawing attention to these environmental issues within her creative practice it will encourage others to reflect on the environments they care for too.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your body of work Monett & Sedalia you create images of Tyson chicken plants. As with many of your works this piece is driven by engagements with place and location, in particular this piece was created near the waterways of Monett and Sedalia that surround the poultry plants in rural Missouri. These two locations have been the site of past environmental disasters. Can you tell us a little bit about why you selected this site and what is happening in this area that is contributing to algal blooms and dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico?

Kari Varner: In 2017 while living in St. Louis, I was working on a project that required me to spend many hours at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. During this time, there was a particularly severe algal bloom in the Gulf of Mexico resulting in red tide conditions that persisted in some form through 2018. Concurrently, a small town in Kansas was fighting to prevent the building of a Tyson Chicken plant just outside of town limits. While witnessing the meeting of the longest rivers in North America, one rising from Montana and the other Minnesota, I was considering accumulation and all that the rivers carry as they accumulate. I wanted to engage these ideas of connectedness of our waterways but bring the work back to a human scale.

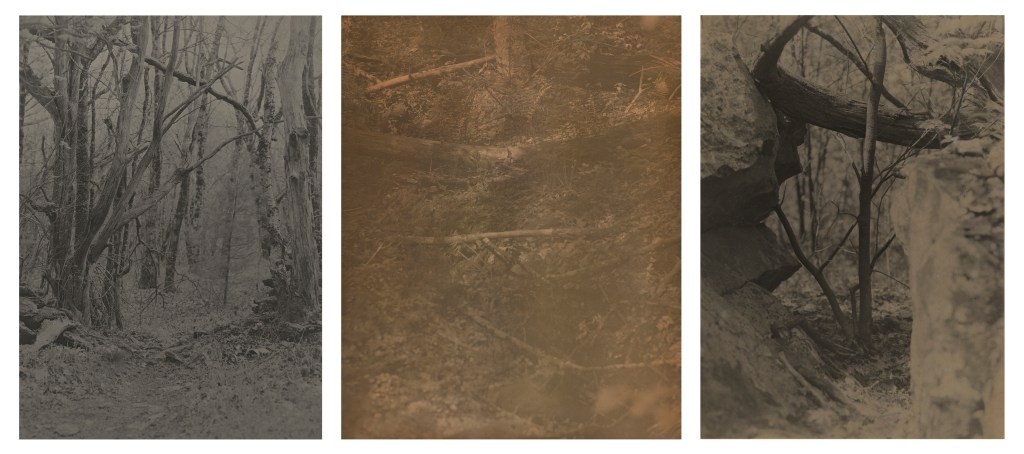

The towns of Monett and Sedalia are like many others in that Tyson and other meat processing operations provide many jobs but also result in persistent environmental degradation. In the waterways of Monett, an ammonia leak resulted in a 100 percent fish kill in 2014 while in Sedalia “between 1996 and 2001, the plant repeatedly discharged untreated or inadequately treated wastewater from the Sedalia plant in violation of the limits in its discharge permit.” Tyson is one of many companies that dump effluent, rich in nitrogen and phosphorus into our waterways. This leads to hypoxic conditions in both fresh and saltwater ecosystems. Traveling to Sedalia and Monett and photographing the waterways and exterior structures of the Tyson plants allowed me to in some way draw a more intimate connection from these individual sites of environmental calamity to the much larger disasters happening on a grand scale.

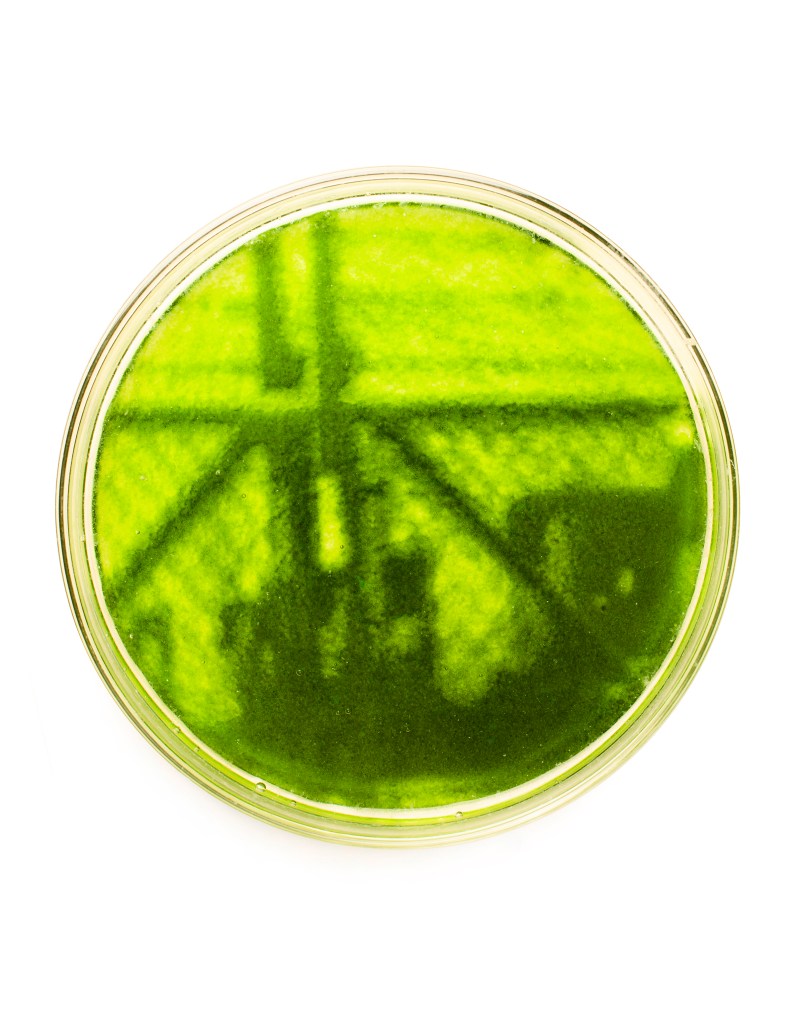

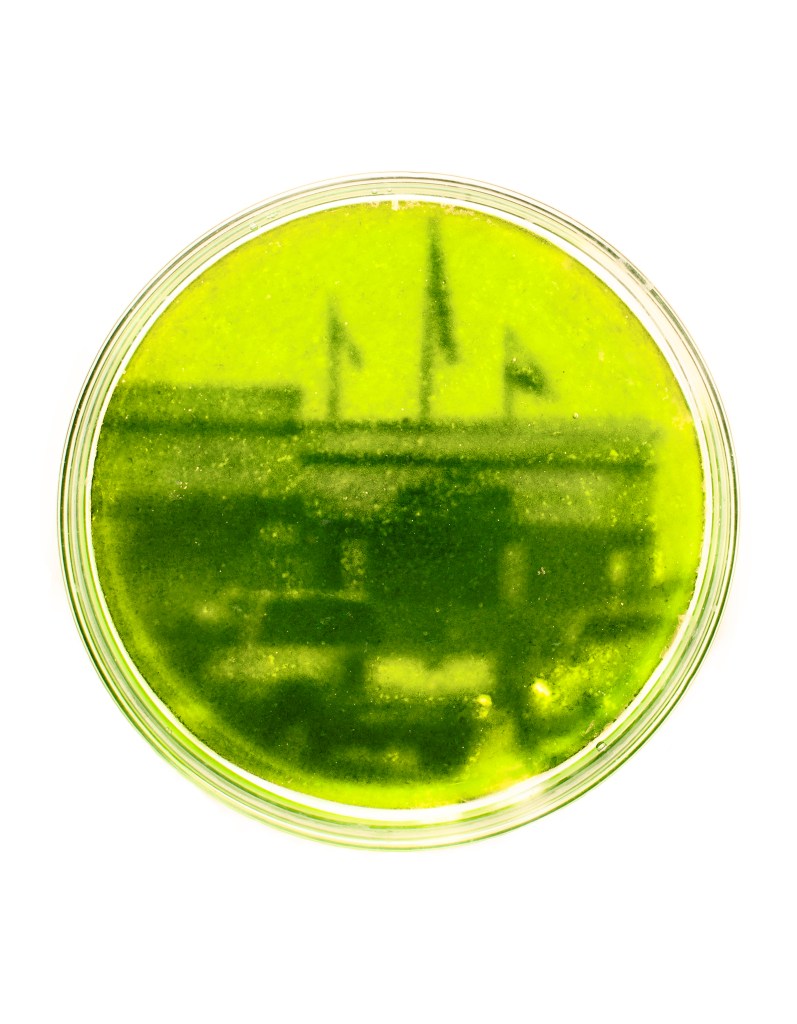

Elizabeth Ransom: The outcome of Monett & Sedalia are framed images of algae, but the process of creating the work is a much larger endeavour. Can you tell us a little bit about the unique process of growing algae that was used to create these images?

Kari Varner: After making the photographs in 2018, I dabbled with some ideas but couldn’t find a suitable format in which to show the work. Finally, in 2021 I had the idea of growing the images in algae and therefore tying the materiality and process of making into the subject of the project itself. After finding the astounding work of French artist Lia Giraud and her creation of the algaegraph, I knew that the process was possible. Using the microalgae chlorella vulgaris, I conducted many experiments with types of nutrients, using an enlarger vs a light table and generally working to identify suitable growing conditions for the algae to thrive. The photographs take a week to emerge and require the pipetting of nutrients into the Petri dish. I was living in Florence, Italy at the time, a much more humid environment and have now moved to a cooler and drier climate. This has required me to recalibrate the algae growing process. I do consider the work ongoing, with the next stage focusing on the photographs of the waterways, which are more abstract and therefore more technically demanding in the kind of “resolution” needed to achieve a readable image. Once the photographs have been grown, the resulting image is scanned and photographed. The photograph is then printed while the algae itself dries and the photograph begins to fade. I have explored possibilities of creating a time-lapse of the growth or bringing the growing process into an exhibition space but for now the work is presented as a document instead.

Elizabeth Ransom: There is an element of labor and care that is involved in the process of rendering these images. What was it like to take the time to grow these works of art and what were some of the biggest challenges you faced when working with natural materials?

Kari Varner: Labor has become a really essential part of my process because it is through these acts of labor and care that I develop a relationship with material and place. When producing photographs using natural materials I consider the formation of the work as an act of collaboration. There is a lot of uncertainty and variability that comes with using natural and particularly living substances but approaching my practice as a collaboration allows me to embrace what the material offers while also recognizing its limits. The greatest challenge in the making of this work was this initial negotiation of determining the capabilities and limits of the algaegraph. There was more failure than success and like anything, it was the little victories that spurred me on. When you are spending months trying to convince a living substance to grow in a desired formation, your level of investment becomes quite high. Ample patience and flexibility were required, but once I saw the first hint of the Sedalia water treatment plant in my petri dish, I couldn’t imagine presenting the work in any other form.

Elizabeth Ransom: You use alternative photographic methods to explore the representation of landscapes that have been directly impacted by agriculture and other forms of human-made erosion. Why do you use alternative photographic methods such as growing algae to investigate environmental issues?

Kari Varner: I view the use of natural materials as integral to the formation of the work’s language. Not only does the use of plants have a direct visual impact on the work, but the photographs cannot come into being without this organic alchemy. One would assume the series Monett and Sedalia would drive me away from making things with plants but instead I have found even more ways to collaborate with them! I am currently making print and paper developer from invasive plant species and the process has been equally thrilling and humbling.

By using these materials, I become implicated in these processes of environmental alteration. Our impact is felt in the traces within the land and water and through the presence of these materials that we have introduced or had a hand in proliferating. I am also interested in exploring how we assign value to an environment, plant or animal species. By using invasive species, which are often labelled as destructive and worthy of eradication, I am acknowledging the complexity of living within an altered ecosystem where the plants are both beautiful and undesirable.

My ongoing experiments have been informed by the excellent resources published by The Sustainable Darkroom and the wonderfully named blog https://yumyumsoups.wordpress.com/ by artist and film maker Dagie Brundert. To make work with sustainable materials is to allow nature into the process. The photograph is not a separate and sterile entity but rather a vulnerable, mutable and sometimes ephemeral form.

Elizabeth Ransom: In what ways do you think art can influence perceptions of human’s impact on the natural environment?

Kari Varner: The urge to interpret place through images is deeply human and now feels especially urgent. Photography allows me to forge connections with an environment as I forage for both plants and images. By bringing my photographs closer to nature and incorporating natural material directly, I hope to encourage others to reflect on the environments they care for. This appreciation could be all that results but this appreciation could also lead to activism, a desire to learn more or in the case of artists, a reconsideration of the materials they use and the source of those materials.

When I think about our impact on industry and agriculture, it can seem too overwhelming to approach. By bringing invasive species into my practice an environmental destructive plant is extracted from the land but adopted into the creative process. The land has been altered and our impact is acknowledged but a complete reversal is impossible. Instead, small individual acts, organized activism, along with passage of long overdue legislation can provide pathways for positive impacts and a shift from an ethic of anthropo to ecocentrism. Ultimately, my work becomes an invitation to learn more and think more deeply about place while considering the intentional and inadvertent ways that we have left our traces on the land.

For more information about Kari Varner and her practice please visit her website HERE

Leave a comment