23 July 2024

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

In an time when we are constantly inundated with pictures, how can photographers create an image of the climate crisis? How can they make audiences pay attention? Canadian artist Ella Morton uses experimental approaches to create sublime and unique works of art that evoke the emotion of visiting remote arctic landscapes. By depicting these vulnerable places in a sometimes eerie and unnerving way Ella is able to draw attention to the magic of our natural environment while also addressing the destruction that is taking place.

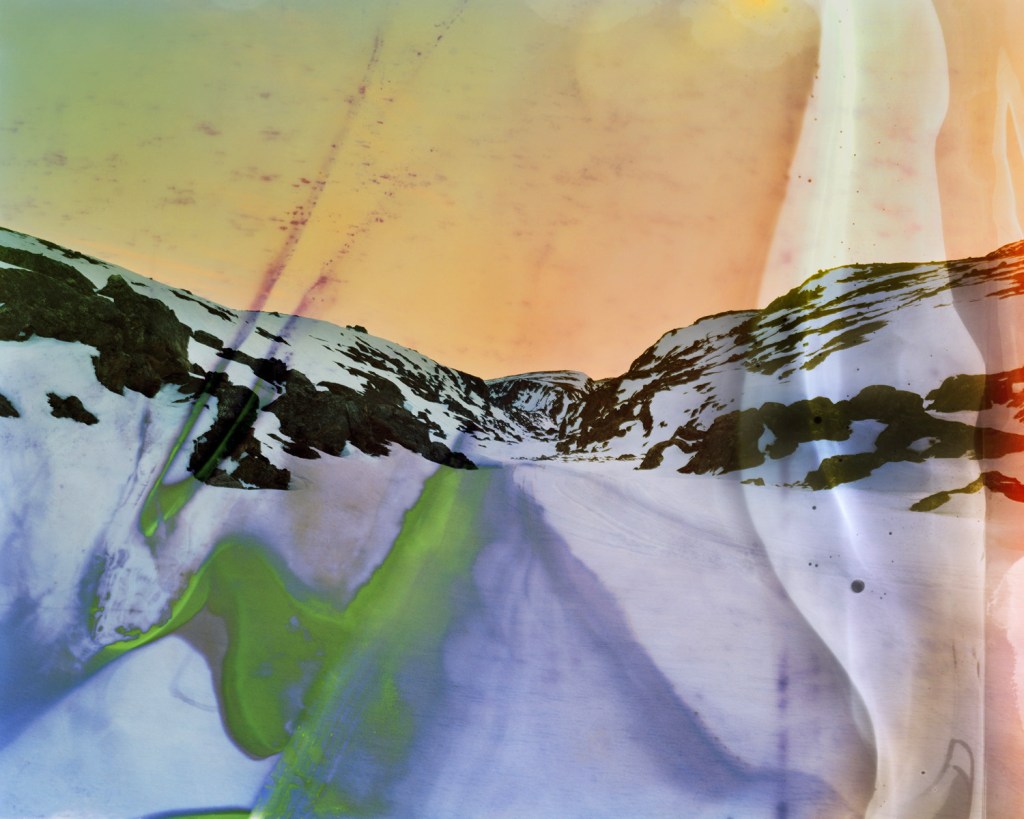

From the series The Dissolving Landscape

Elizabeth Ransom: Your creative practice is expedition based and involves travel to remote landscapes. Can you tell us a little bit about your travels and your process of using alternative photographic processes while abroad?

Ella Morton: When I’m away on these trips, the focus is shooting and experiencing the landscape, walking through it and picking up whatever it gives me. I’m also finding compositionally the places that speak to me the most. I then come home and work in the dark room using various processes. These places that I visit are sublime, it’s like going to another planet. Growing up in Canada, when you see a map of Canada in school as a child, all the main cities are along the southern border and then there’s all this space above that you never really learn about. I grew up with an insatiable curiosity for these places. As an adult I started travelling there and got addicted. Part of my creative process involves being in a state of unfamiliarity and navigating through that. There’s something about unfamiliarity that I find very inspiring.

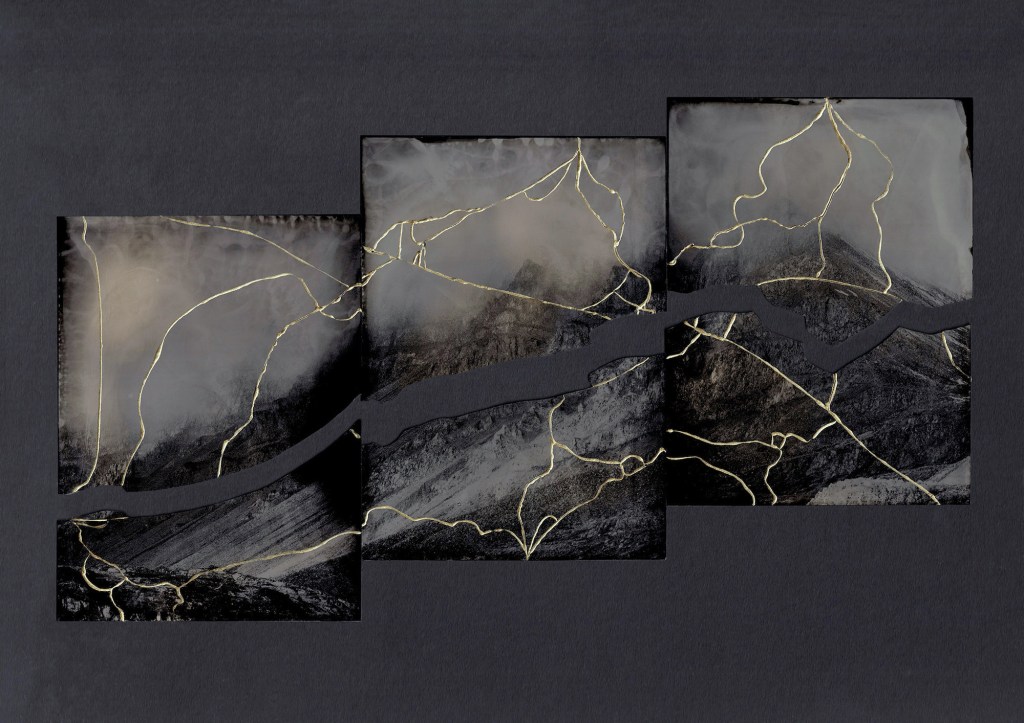

From the series Procession of Ghosts

Elizabeth Ransom: Procession of Ghosts uses the Japanese technique Kintsugi to discuss the fragility of polar landscapes. Can you tell us a little bit about what is happening to these spaces and the meaning behind using the Kintsugi technique?

Ella Morton: My work is about this duality between the sublime and the fragile. It is about the magic of these places, but also their impending destruction and dissolution with climate change. This project, however, started from a personal place. It was about four years ago when my mom passed away from cancer. When she was diagnosed, and as her illness progressed, I had this image in my head of broken glass. Particularly when you’re sitting in a car, and somebody has thrown a brick at the windshield, and it’s broken. I had this assumption that she would live a long life, and then suddenly that assumption was shattered. I kept thinking about broken glass, broken glass, broken glass, and then I realized there’s the technique of wet plate collodion you can make ambrotypes on glass with. I started thinking about how I could work with this photo process while also breaking the glass. It made me think of Kintsugi, the Japanese technique which is normally used on ceramics. They’ll take a ceramic bowl, vase or plate, and break it, and then glue it back together with gold in the cracks. The concept is that the object is more beautiful after it’s been broken and put back together. On a personal level this work is about me being broken and trying to put myself back together. But also, it’s an amazing metaphor for the state of the earth, the climate and our relationship to the environment right now, which is broken and some of us are trying to put it back together.

In 2021, I took this trip to Antarctica. It was a self-funded trip that I wanted to do after my mom died to celebrate life again. I decided that I would make the focus on ice, icebergs and glaciers. The title Procession of Ghosts refers to the ghostly characteristics of ice. For example, ice looks quite ghostly in its beautiful white colour, while also the ice is becoming a ghost as it gradually disappears. Procession refers to how ice is always moving. In 2019 I went to Nunavut, and you can be standing out on the frozen bay, and you’re standing on what seems like completely still ice, but the tide still moves it up and down throughout the day. Glaciers are constantly moving. I’ve also done several trips to Newfoundland and Eastern Canada and every spring there are icebergs that come down along the coast of Newfoundland from Greenland. In a way they are like a procession of ice. Each year the procession becomes much more irregular. This project is an effort to capture this beautiful and sublime part of nature that’s disappearing and changing.

From the series Procession of Ghosts

Elizabeth Ransom: In Procession of Ghosts, you also use wet-plate collodion ambrotypes on black glass in the style of traditional landscape photography. You then abstract the landscapes by smashing the glass, joining the cracks back together, and creating multiples within one picture plane complicating the image further. Can you discuss the use of fragmentation and abstraction in your practice?

Ella Morton: With Procession of Ghosts part of the fragmentation comes from the process itself. It is logistically difficult to make a big wet plate. So that’s part of why I’m working with multiple plates put together to make one larger image. The wet plate collodion process can be done on glass, which is easy to break into smaller pieces. Some pieces are glued back together, and some are not which ties in with the theme of that project.

The abstraction in the work speaks to the state of photography in the present day. In the last twenty years or so, as digital photography, smartphones and social media have established themselves, images are generated and shared all the time. I have to ask myself why I am going to all this trouble to go to these remote places when I could just type the place into Google and find hundreds of thousands of images of it. How can I make an image of these places that doesn’t already exist, that you can’t just find on Google somewhere. What am I contributing? I think that’s where the act of abstracting comes in.

There’s a photographer whose work I really like, Sarah Anne Johnson. She’s from Winnipeg and she discusses how photography is good at showing you what something looks like, but it’s not always so good at showing you what something feels like. So, the act of abstracting or altering the image is an effort to show what it feels like to show that kind of a lamentation of here’s what we have. Here is how beautiful and amazing it is, and it’s falling apart in front of us. Here is the depth of what we’re losing if we allow these stunning places to change and dissolve. I also think that as digital photography and social media has become more popular the analogue camera has become obsolete. The technology of analogue photography has been freed up for artists to do cool stuff with, because it no longer has this obligation to document reality. I’m abstracting what I see in front of me in the landscape for all those reasons, to respond to the changes in photography as a medium and to try to capture what the thing feels like more than what it looks like.

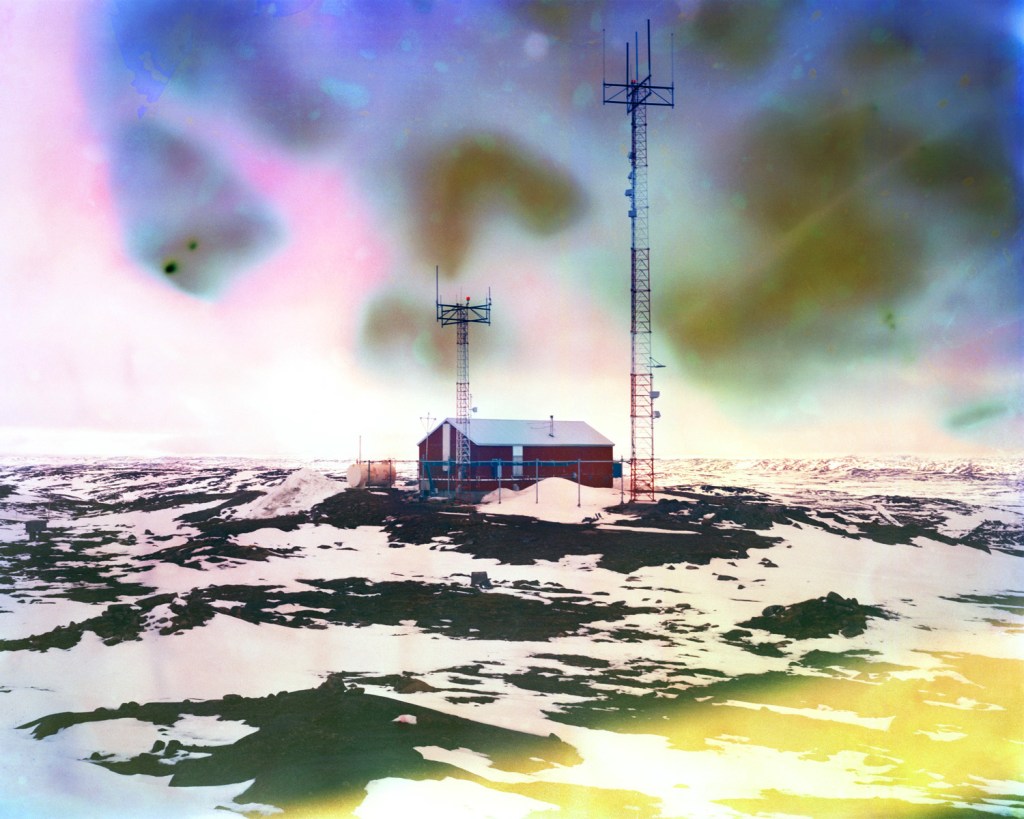

From the series The Dissolving Landscape

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series The Dissolving Landscape you address the pressing issue of climate change and how vital our relationship to the land is. In 2019 you travelled to the Canadian Arctic to photograph the landscape around Iqaluit and Pangnirtung, Nunavut can you tell me what is happening in this area that is causing such concern to the local people?

Ella Morton: The effects of climate change are more acute the closer you go to the poles. The further north or south you are on the planet, the more extreme and faster those areas are warming compared to other parts of the planet. I’ve watched a lot of Inuit made documentaries, and they’ve been talking about climate change since the seventies, they’ve been noticing changes in animal migrations and weather for many decades. There are also new airborne chemicals from other parts of the world that travel on wind currents and ocean corridors to the north. There are lakes where the flora and fauna have been destroyed by chemicals and are now considered dead lakes. These contaminants and chemicals enter the bodies of animals which then affect the humans who eat them.

From the series The Dissolving Landscape

Elizabeth Ransom: The mordançage process is striking and mysterious as well as the bright and engaging use of film soup which you also have explored in The Dissolving Landscape series. Why did you choose to use these processes? Do you find using unique processes such as these can bring much needed attention to urgent issues surrounding the environment?

Ella Morton: These processes have the capacity to show a feeling, or create an emotional connection, or evoke an emotion about the landscape that you see in front of you. Much more than you could just taking a straight digital photograph. I think, especially with mordançage I just fell in love with the veils, and the stormy, eerie, unnerving, menacing look to it. I think this process depicts really what I was trying to capture in the landscape itself, and what I feel in the landscape. It’s the same with film soup. Film soup can take on different forms depending on what you soak it in. Sometimes you will get warped colour, different textures, it can look like the land is being poisoned, or sometimes it just makes it look more beautiful, sublime and luminous. I think both processes have that range of showing the magic of the landscape, but also the destruction and everything within those two sides of the spectrum. Especially with the polar landscapes or with all my travels in the Arctic, there is a power to that latitude and those landscapes that you can’t really know until you go there and experience it. It grips you in this really special way. I think these alternative photographic processes begin to capture that. I’m not sure if I’ve ever completely captured it, but they get close to capturing that power.

For more information about Ella Morton and her practice please visit her website HERE

From the series Procession of Ghosts

Leave a comment