25 December 2023

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Megan Bent’s current exhibition at the Cultural Equity Incubator Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts showcases Bent’s body of work Latency a powerful project that explores representations of disability and illness. She juxtaposes news clippings and medical documents alongside portraits of folks with non-apparent disabilities to break down stereotypes. Printed on plants Latency uses the chlorophyll printing process as a mechanism to visualise vulnerability and impermanence. Slowly, the Sun Weaves Past Into Present is on view until 12 February 2024.

Marginal Erosions, 2019 chlorophyll print on betel leaf.

Image description: A dark green betel leaf on a black background. The leaf is shaped like an upside-down heart. Printed into the chlorophyll appearing in lighter green is an x-ray of my hand. The bottom of my hand rests and the bottom of the leaf and my curved fingertips touch the very top of the leaf.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series Latency you use the chlorophyll printing process to explore how illness and disability are represented in society. Could you tell us a little bit about the methods behind creating these images and why you have chosen this specific alternative photographic technique to visualize your lived experience?

Megan Bent: In 2017 I started printing for this series. I had taught myself chlorophyll printing a couple of summers before and fell in love with it. I always have so much admiration and gratitude for the artist Binh Danh who invented the chlorophyll process.

Essentially it is using photosynthesis to print images into the chlorophyll of leaves. There are a few methods of doing this.

What I do is:

- I print the image I want on the leaf on transparency film

- I pick the leaf I will print on

- I combine the leaf and transparency in a contact printing frame. Transparency on top of the leaf in the frame

- I leave it in the sun to expose. Exposures can take hours or days depending on the time of year and visible sunlight.

For a while, I had been thinking about the experience of living with something that defined every aspect of my life but was unknown to most people and the complexities of navigating that.

Then attacks on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) started happening in Congress. And before I get into that more I want to share unequivocally that I want healthcare for all and will continue to fight for that. But when the ACA was being attacked, this brought out a lot of fear and rage in me. I have experienced denial of care due to having a “pre-existing condition” and facing impossible decisions like paying out of pocket for surgery (going into debt) or living with intense daily chronic pain (I chose the latter).

So this idea to print from my medical imagery and show what was happening inside my body took off then as a response to this. I was thinking about not only how the overturn of the ACA would affect me, but how at that point it was 1:4 people in the US were disabled (now I believe it is 1:5, and with long COVID there is going to be a dramatic increase occurring in the disabled population.)

I requested my x-rays from my doctors and started to chlorophyll print them. At this point, I also made an important decision, and I think a departure from how chlorophyll prints are usually treated – I decided to not fix them and let the leaves continue to age and decay.

Section 504 Sit In 1977, 2019, chlorophyll print on hosta leaf.

Image description: A vertical oval-shaped hosta leaf on a black background. Printed in the chlorophyll is the original 504 Sit-In poster from 1977. There is bold text “The Federal Government is Trying to Steal Our Civil Rights! DEMONSTRATE to demand the signing of 504 regulations!”

Elizabeth Ransom: This work shines a light on the subtleties of hidden disabilities including identity and stigma surrounding the medicalized body. What has your experience been living with a hidden disability and how has using alternative photographic processes helped you to challenge misconceptions surrounding illness and disability?

Megan Bent: I would say first and foremost printing my medical imagery was a way to assert my identity as a chronically ill/disabled person.

I have been thinking about this a lot recently, earlier I mentioned I had to forgo surgery until after the ACA passed and could have the operation covered by insurance. So there were several years where my disability was physically visible. It was this very apparent and present thing in public spaces. And there is identity and stigma attached to that experience. This was a time when I was beginning to form my disability identity and discover disability culture. When I was out in public I would get stared at, and have strangers ask me “What’s wrong with you?” Or “What’s wrong with your leg?” I had people start making decisions about my capabilities for me, disempowerment. And this all stirred up in me this sense of defiance, staring back, speaking out.

When I had surgery, it was so important because the amount of physical pain I was living with was intense. But so much changed after that in complex ways. There is a privilege, in a sense, in not having my disability apparent. And as I healed, and as my limp disappeared I did feel this loss of identity I had to grapple with.

In public, I noticed nobody stared anymore, and the invasive questions stopped. But then there is also this new layer of complexity, having to continually disclose my disability over and over again. Choosing when and who to share it with. And then there is the stigma of not being believed because it is not apparent. In work situations, this has been extremely challenging and stigmatizing. Or the fact that my disability is dynamic, meaning it’s a chronic illness and symptoms change from day to day. So you know like “Why could I do x on this day but can’t do it now?”

Going back to 2017 and ACA, at this point there were a lot of conversations happening about care for sick and disabled populations and linking it to morality. Like if you are sick you must have made a bad decision or not taken care of yourself so you deserve whatever is happening to your body/mind. I think so much ableism stems from the denial that disability will happen to everyone. And I wonder what society would be like if we leaned into the impermanence and interdependence we all share, within our bodies, and with each other.

So in making this work, it felt really important for the imagery to come from this place of claiming, representation, and assertion. And the process to underscore our shared vulnerability, that all our bodies will change, this is universal, so why can’t we embrace bodily diversity?

In this series, I reached out to other folks I know who have non-apparent disabilities asking if they wanted to share their imagery or ideas about what was non-apparent or invisible about their experiences. So I had friends and family members sharing their imagery with me, x-rays and medical bills for example. Or generating ideas for prints through conversation. Then I started to pull or create imagery related to disability history, slang, companionship, care, and community. This enriched everything because more layers of experience were entering the work.

There are so many stereotypes about disability and there is a lack of authentic representation. I was really isolated from other chronically ill/disabled people when I was first diagnosed and all I had was the mirror society held up to me. So I spent a lot of years feeling shameful and even afraid to let people know about it. And when I found community and learned about disability history it changed everything. I feel like a major driving force for me and a hope with the work is to create space for that representation, conversation, and connection.

Gary, 2018 & rescanned in 2023 chlorophyll print on elephant ear leaf.

Image description: A heart-shaped hosta leaf on a black background. Printed in the chlorophyll is a portrait of an older man, my Dad, from the side. His face takes up the whole leaf. The print on the left is highly detailed and a vibrant green The print on the right has a yellow hue and the print has faded significantly.

Elizabeth Ransom: There is a vulnerability that is present in your work. At the forefront you have the vulnerability of the subject matter as you explore personal stories of disability and then in addition to this you also refer to the vulnerability of the image itself. These works are printed on plants. The plants will age and decompose over time in addition to the image which will eventually fade away as it is exposed to light. Can you tell us a little bit about the connection between bodily impermanence and the vulnerability of nature?

Megan Bent: Vulnerability, to me, is strength and vulnerability is a really important component of the work. I initially wanted to work with plants because of our connection to nature but also the ways I think that we, society, have so much to learn from nature.

I was thinking a lot about life cycles and nature cycles. When leaves change in the fall, this is a part of the plant’s natural process and the leaves are dying. And to so many of us, it is so beautiful and revered, this vulnerable season of fall. And then when it comes to the vulnerability of our bodies, changes in our bodies, or aging, there can be this extreme discomfort or pushing away of that experience.

I think a lot about toxic individualism, especially since the pandemic. I have this really deep gratitude and appreciation for how disability communities are really interdependent and care-focused. That has been life-changing.

However, individualism is so pervasive and ultimately damaging. I think about the mycelium network and how we now know trees share resources through that network. If a tree is sick nutrients will be shared, if there is a threat, communication will be shared, if there is a lack of resources in one area trees in places with more abundance share their resources.

When I first decided to not fix the leaves I had no idea what would happen, or how long they would last. It has been almost seven years and no leaves have completely faded yet. Some are very very faint. And I think this work has been a deep experience for me, being with the work for so long as it continues to change.

I became their caretaker. For example, if I keep them pressed in books when not on exhibit, that care helps them have longevity. If I did not provide this care, if I left them out around UV light they would quickly fade and disappear. I see this as a commentary on access to proper care. And I think letting the leaves biodegrade is an important statement about the impermanence and vulnerability we all live with.

Through this process, I also discovered that the act of making is very much related to the experiences or values I have found in the disability community. The process celebrates care, flexibility, slowness in time (and appreciating that slowness), interdependence, embracing uncertainty, and creativity.

Arthroplasty 2018 & rescanned in 2023 chlorophyll print on elephant ear leaf.

Image description: A large heart-shaped hosta leaf on a black background. Printed in the chlorophyll is an x-ray of a total hip replacement. The print to the left is made from a scan of the leaf when the first print in 2018. The image on the left is the leaf rescanned in 2023. The leaf has more of an umber hue and has faded.

Elizabeth Ransom: Latency juxtaposes portraiture with medical imagery including brain scans and x-rays. Where did you source this material from and how are you using these images to reclaim medicalized bodies?

Megan Bent: Much of the medical imagery present in the series is from my X-rays or my father’s X-rays. We requested to have these images from our doctors. It got to the point, because I get X-rays so frequently, that my doctors just knew I would want copies and give them to me.

Through this process of collaboration, especially collaborating with my father who was living with stage 4 melanoma, it became this process where we were excited about making this work together. And it transformed our medical imagery and medical experiences altogether. So often when you are in the medical setting, you need this care, and also you experience parts of yourself being described in really negative ways. It’s hard not to internalize that. This process of chlorophyll printing our medical imagery, helped us move beyond the label of patient.

The chlorophyll prints were taking these medical images of “deficient” parts of ourselves and with love and care making them into temporal pieces of beauty. My dad would show his oncologist the work with excitement. It provided this reclamation of agency. It created community and a deeper bond between us.

When I started the series that was not a part of it I imagined, but it is one of the most beautiful things to come out of creating this work.

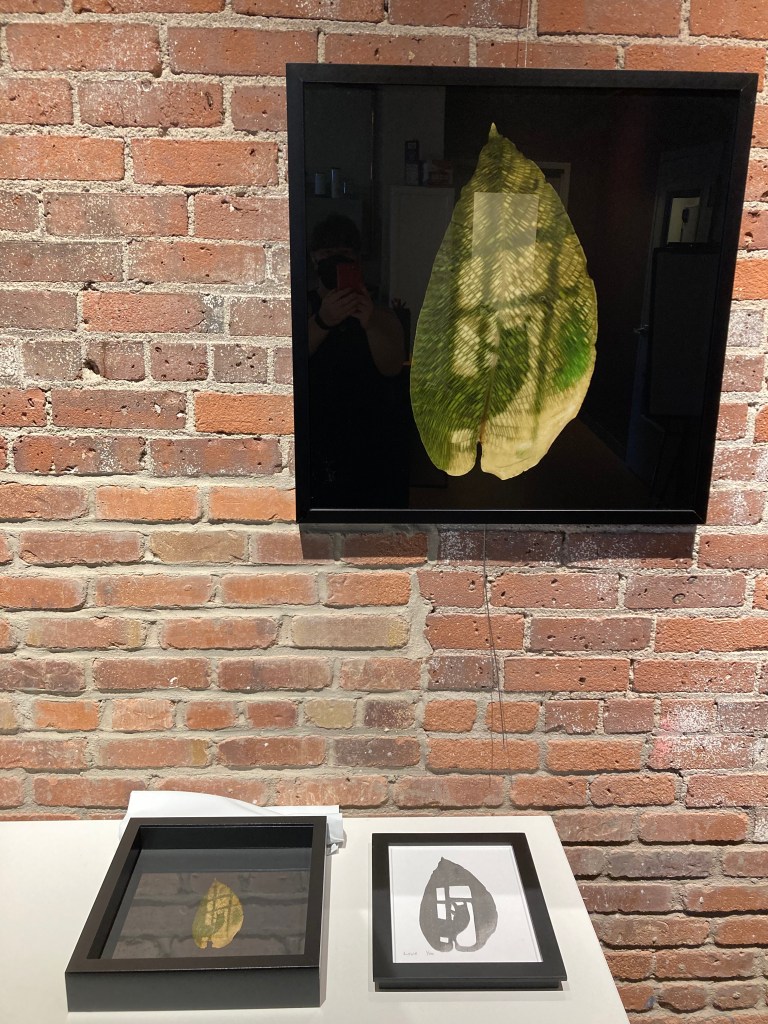

Slowly the Sun Weaves Past into Present, Installation image, Cultural Equity Incubator Gallery, Boston MA. 2023.

Image description: A grouping of a digital print, chlorophyll print, and tactile representation. The image represented in all three is the shadow of my arm extended with my hand making the “I Love you” sign in ASL. It is printed on a checkered prayer plant leaf.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your current exhibition Slowly, the Sun Weaves Past into Present at the Cultural Equity Incubator Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts you have incorporated braille and tactile elements to the work by including high contrast and embossed/raised works of art that can be touched. This allows those who are blind or have low vision to be able to enjoy the exhibition. What can artists and galleries do to create more inclusive environments for those experiencing disabilities or illness?

Megan Bent: Accessibility in the art environment has been something I have attuned to since my MFA exhibit in 2012. In planning that show I researched how to create an accessible exhibition. It had access features like seating, all the work installed at an accessible height for wheelchair users, large print text, and high contrast print and visuals. And I am continually learning.

Over time, I also started including access statements so that these changes in the space were explained and highlighted. I had always wanted to have work that included touch and I didn’t know how to do that as a photographer. Recently I learned about tactile representations, which are a recreation of the visual compositions done in high contrast and on a paper where the composition is embossed and can be felt with touch. There are also Braille annotations on the page. This has been exciting and something I want to be part of every exhibition going forward.

These are specifically made as an access feature for people who are blind or have low vision. And when things are accessible it benefits so many people. Many people who are sighted have also shared their excitement at having another entry point into the work and experiencing the work through touch.

I just want to say again that I am continually learning and striving to create art where access is an integral part of the creative process. I know I will continue to learn new things and ways to be more accessible and then change my practices accordingly.

In terms of artists and art spaces, there is much that can be done – both in-person and digital art spaces are inaccessible in numerous ways.

Some things that can be done (not an exhaustive list):

- Add alt text or image descriptions to artwork (on social media, websites, and in the art space)

- Hang artwork at an accessible height for folks who are wheelchair users

- Prioritize seating in the art space

- Having tactile representations or tactile elements for visual artwork

- Providing text in large print and braille formats

- Having an access statement on the website and/or in the art space

- Advertising access features online and in art spaces

- Having a contact person for the art space who can answer questions and access requests

- Continue to offer remote options for connection and engagement because in-person remains a barrier for disabled communities (immunocompromised folks, transportation can also be a barrier)

Some resources that can help folks get started:

Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice

https://promiseandpractice.art/

(free PDF download!) by Carolyn Lazard

Alt Text as Poetry

https://alt-text-as-poetry.net/

By Bojana Coklyat and Finnegan Shannon

(explains alt text and provides resources and prompts to begin writing alt text)

Accessible Social

https://www.accessible-social.com/

(Amazing website with SO many resources)

Access is Love

https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2019/02/01/access-is-love/

(Writing and resources!) created by Alice Wong, Mia Mingus, and Sandy Ho

Access is Love Further Reading List https://docs.google.com/document/d/1TY9k_S0oLUVXEhI1FdmT8yaG_28cbcBStuyM9wXag6k/edit?pli=1

For more information about Megan Bent’s work please visit her website HERE

Low Energy, 2019 chlorophyll print on hibiscus leaf.

Image description: A round yellow hibiscus leaf on a black background. Printed into the chlorophyll is a self-portrait during a sick day. I look at the camera with a blank stare, have long hair and bangs, and am wearing a shirt with “Sleater Kinney” on it.