25 October 2023

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

Based in the United States, photographer and educator Eleanor Oakes turns the historic photographic process of salt printing upside down to create intimate scenes of motherhood. By collecting her own breast milk and the tear drops of her child she is able to create salt solution that is used for salt printing. Eleanor’s work investigates acts of care, representations of motherhood, and labour related to mothering.

Amit and Lior, 2023. Salted paper print made with Amit’s breastmilk, 9×13.5.”

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series Milk and Tears, you use the salt printing technique to create images that visualize the experience of motherhood. With the use of your own breastmilk and your child’s teardrops, you are able to create a light-sensitive photographic emulsion to record images with. Could you tell us a little bit about what salt printing is and what led you to develop this unique twist on the process? Were there any unexpected challenges that arose when experimenting with this new approach to salt printing?

Eleanor Oakes: I would be delighted to, and am so honored to be featured here with you Elizabeth!

The salt printing process was one of the first photographic processes ever invented, presented by Henry Fox Talbot in 1839. As a negative to positive process, it became the precursor to most imaging of the 19th and 20th centuries, and yet there are very few women I can find who worked in this process throughout the history of photography, and hardly any representations of motherhood.

Where my path converges with the history of the salt print was rather a happy accident. In a sleep-deprived haze when my son was 6 months old, I signed up for a course at Penumbra Foundation in New York with the amazing Christine Elfman. I clearly didn’t read the course description very well, as months later when I was preparing what to bring to the class, I realized we would be making ‘photogenic drawings,’ Talbot’s first iteration of salt printing before the invention of fixer by Sir John Hershel. This was in September of 2021, so I really hadn’t travelled since COVID lockdown, nor becoming a mom. I was still breastfeeding but didn’t have any infrastructure to transport milk, so I knew I would be pumping in my hotel room (or the bathroom at Penumbra) and then dumping my milk down the drain. I didn’t want to waste it, so I asked Christine if she would be ok with me experimenting with it as a salting solution. That weekend I got a few first prints to expose, and then took the process home to continue my work on refining it and challenging what it could do.

My first challenge was measuring salinity. Salt prints call for a salt solution of 2% salt water, but what the heck was breastmilk? I dove into a lot of nutritional research to try and determine the salinity of breastmilk, eventually realizing it was much lower salinity than desired. After a long night up with my son, I realized I could use his tears as an additional salt source to mix with the breastmilk, so I started collecting them in a small jar whenever he cried. Hence the name of the project became Milk and Tears.

The next challenge came in fixing the prints. I tried many different variations before finding one that has made the prints stable. I also wax the prints as a final step to enhance their archival life. This is our complicated relationship with photographs, we want so badly to fix them, make them permanent, while also knowing that in the grand scale of geologic time, nothing is ever permanent. This is even more true for our relationship to memories. I wanted to fix these images the same way I want to fix my memories of my child at this time, as we both are getting older each day.

These works have remained incredibly stable in my tests, although how stable they will be long term remains to be seen. However, despite my persistent efforts to fix this work, I like having this reminder that nothing is forever, that all our attempts at preservation are ultimately a futile exercise fuelled by our own human fragility.

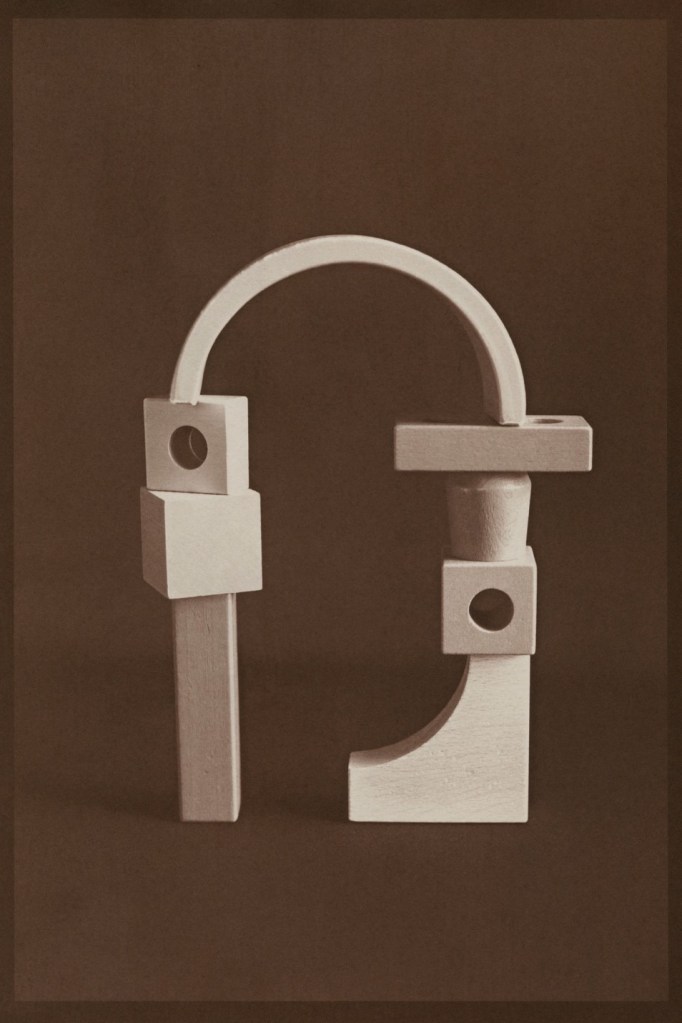

Balancing Act (1), 2022. Salted paper print made with breastmilk, 9×13.5.”

Elizabeth Ransom: The representation of motherhood in fine art photography is wide-ranging. From the work of Rineke Dijkstra who photographed three women moments after giving birth. In her images, a trickle of blood and a glimpse at a cesarean scar reveal the physical and emotional intensity of the experience of childbirth. To the heart breaking mural piece created by Sheila Pree Bright of mothers who had lost their children to police brutality. Motherhood is an immense topic to investigate. What aspects of motherhood inspired Milk and Tears and what was it like to use your own personal experience of motherhood as a source of inspiration?

Eleanor Oakes: The representation of motherhood in photography and art might be wide-ranging, but it is also feels rarely lauded. I’d also add that I think of the terms ‘motherhood’ and ‘mothering’ as being inclusive, meaning anyone who self-defines as a mother and a caregiver and not being restrained to biological sex. To summarize the feedback Rineke Dijkstra received after displaying her images, the women were grateful for an honest representation of that moment, but “the men were all like, you can’t show a woman like that.” It feels like we still have a long way to go in grappling with art through mothering, and even what ‘acceptable’ representations of parenting are in both art and popular media.

Our tropes of parenting photography feel heavily tied to the “cute,” but the counterpoint to that is trauma. I think about works like Patty Chang’s Milk Debt, or the photographs of Jon Henry, both are so tied to the loss and fears of parenthood. Above all else, my experience of parenthood has been that it is hard. And becoming a mother during COVID was a very isolating experience. Parents, caregivers, and essential workers definitely don’t get enough credit for the work they do.

Using my own experience with motherhood as a source of inspiration was no different from other works I’ve made, as I think most of us are always drawing from our own lives in making creative work. I do think this work is about much more than motherhood however. Representations of motherhood in this work are an invitation to think about care more broadly, and how we think about our roles as individuals within the greater communities and ecosystems in which we function. Even thinking about how we interact with the environment, if we are being healing or harmful. My hope is that through this recognition of maternal care, we can start to appreciate the value in acts of care more broadly.

I’m also grateful for how this work brought me through a transition in my research. I felt a dearth of creativity throughout my pregnancy and early motherhood, but working through this process brought me back to my practice, and for that I am immensely grateful. It also opened me up to a whole new process that has been incredibly generative. I don’t think I’ll work in breastmilk forever, and I have already started numerous other projects using alternative salts that I’m very excited for, but I’m motivated to keep working in salt prints for the foreseeable future.

Esther and Danielle, 2023. Salted paper print made with Esther’s breastmilk, 9×13.5.”

Elizabeth Ransom: You have recently received the Flourish Fund Grant from Culture Source and the Andy Warhol Foundation to expand this project to work with a group of mothers and continue making portraits of motherhood. How do you find mothers to work with and what has it been like to collaborate with these women?

Eleanor Oakes: I’m so grateful to Culture source and the Andy Warhol Foundation for their support of this project and to have the ability to share this process with other families. This new iteration of the project, with the working title Love’s Labor is a collaboration with fellow mothers in the metro Detroit area to make intimate portraits of contemporary motherhood and breastfeeding.

Some of the mothers I’m working with found me directly through social media or my website, I reached out to community groups and shelters, and many are referred to me through friends, doulas, and lactation consultants. It’s been a very grassroots project and so many families find me through word of mouth. I’m definitely looking to expand the project next year however, ideally traveling nationally to work with more families, and hoping to include more diverse family models in the project as well. This same process works with formula (although the results are rather different), so I’m hoping to include families who might not be able to breast or chest feed.

As the initial salt coating in this process is not light sensitive, I’m often working with each mother in their own home, teaching them how to coat paper so that their hand is introduced to the work. It also becomes a fun little traveling lesson on salt printing and the history of photography. I’m excited to be including images from some of the mothers’ gardens in the project. I realized that so many of the mothers I was working with have their own practices of care: some of them have family gardens, larger public gardens, make teas, are nurses or practicing doulas and lactation consultants, the list goes on. The garden images honor that extension of care in the project, as well as make ties to continued ideas of food supply and nourishment.

I’ve also partnered with some amazing mothers’ groups and lactation consultants to do larger group workshops that have also been really beautiful events and furthered the community that’s being created through this project. I’m so grateful to all the families who have let me into their homes and shared their feeding journeys with me, I feel honored to tell some small part of their story.

Balancing Act (3), 2022. Salted paper print made with breastmilk, 9×13.5.”

Elizabeth Ransom: Each print within your series Milk and Tears is unique. There are slight irregularities that occur from the fat in the breast milk and the tones of each print vary from warm orange to cooler grey tones. Can you tell us a little bit about how you are using these variations to represent the imperfections of motherhood as a reminder that human bodies are not machines? Have you found that using formula in Love’s Labor also results in similar irregularities?

Eleanor Oakes: When I began this project I had about 11 images I wanted to make, with a goal of 5 editions of each. But the fickle nature of salt prints, the organic nature of breastmilk, and differing levels of salinity all combined to produce anything but consistency. The fear of photographic perfection was gripping, how was I going to be able to reproduce these works so they all looked the same?

Breastmilk is not homogenized, and so no matter what I did to try and emulsify it, fat would still swirl in my coating trays and unpredictable fat spatters or discoloration would still occur. After weeks of struggling with inconsistencies in the darkroom, it dawned on me that of course they should NOT be the same! What a disservice that would be to the nature of the prints themselves and their expression of a human experience that is universal, but unique for all of us. They should be allowed to be as different as our own bodies, which are not machines but imperfect organisms.

I realized that the differentiation between these prints was the beauty of them, the fact that there were parts of the process that were uncontrollable replicated life, and our multitudinous experiences of it. To force them to be the same would be a disservice to them, to make them more boring. I ultimately encouraged these differentiations rather than fighting them. Not worrying if milk was a bit chunky, and even allowing some of the prints to sit overnight after coating them with silver nitrate, allowing the breastmilk and silver to have a conversation through residual fogging.

The same differences that presented in my own breastmilk are equally evident working with other mothers, different tonalities and consistencies of breastmilk yield differing results on the final print, emphasizing the individuality of each mom and family’s choices and experiences. Yet the images also show similarities between our shared humanity and biology.

As mentioned above, I have experimented using formula, and there are a couple moms whose prints actually mix formula and breastmilk to create a real representation of their feeding journey. The real difference with the formula is its consistency. It’s a real visual lesson in the difference between an organic, human-produced product versus something that has been mass produced. It’s also a reminder that they both work, and whichever a parent chooses to feed their baby shows the same level of care they have towards their child’s health and well-being.

Philosopher (1), 2022. Salted paper print made with breastmilk, 9×13.5.”

Elizabeth Ransom: Could you speak a little bit about how you are using the medium of alternative photographic processes to explore the labor and sacrifice that is involved in motherhood?

Eleanor Oakes: Let me circle back here to say that the over-arching challenge to this project was really just being a parent itself – finding time and space for research in the darkroom, in addition to the labor of feeding and pumping milk for my son. There was additional guilt of pumping milk for an artistic process. After my feeding journey ended with my son, I continued pumping for about another month to build up a supply for printmaking. Should I have given this milk to my son instead? After spending a year with constant anxiety over having enough milk, suddenly I had lots and I wasn’t even going to give it to my baby.

I imagine this guilt really has to do with the fact that we’re all striving towards some sort of unreachable perfection. Rather that recognize our own truth, and the beauty of our wild diversity, we’re trying to emulate some societally accepted version of ourselves. Perfection is not an attainable goal. One thing I’ve been thinking about a lot recently is equating this realization to the medium of photography, asking why we think practicing perfection in photography is healthy either. I think as photographers we need to reconsider the perfectionist notions embedded in our medium and counter these notions towards the goal of more diverse and holistic representations.

It’s possible in a not-too-distant-future that analog and alternative process will be the only tool we have against a digital erasure of the hand. I am not suggesting that we all return to making photographs solely in 19th century processes, but rather that we allow room for the imperfections and complications that make us human, both in our practices and our lives. That we allow our practices to develop in uncomfortable ways, and perhaps ways that can address the narrow view of imaging as defined by the history of photography.

Making these prints from breastmilk literally adds my own bodily labor to the print. It also interjects a uniquely feminist narrative into this historical process and the history of photography by inserting intimate portraits of motherhood made through a woman’s gaze into the void of historical representation. This research is my way to literally re-humanize and embody our medium, working with organic, bodily materials, with other families, in imperfect but real spaces, creating prints that try to reinterpret the historical record and create contemporary social conversation.

My experience of both becoming a mother and living through the COVID-19 pandemic has taught me that our modern society still overlooks care as something frivolous and sequestered. My hope is that this work will help expose care as a necessary building block. This work in particular highlights maternal care, but I hope we can see care more generally towards each other as a universal key to a meaningful connection and the path forward to a better future for our students, our children, and future generations after us.

For more information about Eleanor Oakes work please visit her website HERE

Mary and Julian (2), 2023. Salted paper print made with Mary’s breastmilk, 9×13.5.”