25 September 2023

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

You may have seen alarming headlines drawing attention to the increasing number of forest fires carving their way through our natural landscape. From Australia to Hawaii the toll of this destruction is felt by many. Brazilian visual artist Marilene Ribeiro investigates the ongoing human impact that is contributing to the obliteration of wildlife in Brazil and uses alternative photographic techniques to showcase the consequences of government policies, colonialism, and extractive behaviours upon natural and cultural sites in Brazil.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series Open Fire you combine text and image to expose the violence that has been inflicted upon the Brazilian natural landscapes and cultural sites, in particular the unprecedented number of fires that have been burning throughout Brazil. Many of the fires were started by human action, negligence, and lack of resources. What is currently happening in Brazil that led to this destructive situation?

Marilene Ribeiro: Hi, Lizzie! Glad to be speaking to you here.

The point is that this widespread destructive situation that Open Fire encapsulates is not punctual in time, it’s rather a loop – of violence and annihilation – that has repeated year in and out throughout time. Brazil, like many other Latin American countries, suffers from the extractive-based mode we, world’s society, have lived in since modern times, and also from the legacy of colonialism, which still happens nowadays, yet disguised into the contemporary geopolitical norm, national and international policies, etc.. (there are many good reading references in that regard, one I would cite is the book ‘Neo-extractivism in Latin America’, by Argentinian author Maristella Svampa). The truth is that the modus operandi we live to-date is still underpinned by “conquering” and grabbing resources (as much as one can!) from the sites where they exist, and, well, violence is an inherent part of this model of relation, isn’t it? So, what we see currently happening in Brazil is a reflection of this big picture, this socio-economic and political scenario. To “conquer” more and more land over the Brazilian savannah and the Amazon, cattle ranchers and agribusiness people have set fire to natural landscapes so that those areas eventually become ecologically impoverished and, then, open to be claimed as suitable for large cattle grazing areas and monocultures. There is also the mafia of land grabbing (grilagem), in which setting fire in the forest is part of the process. And, on top of this, there is the historic conflict between ranchers and local indigenous communities (which should be entitled to live in their territories), in which fire has been employed by the former as a weapon to threaten and destroy the latter. Well there is also corruption and the lack of value given to our natural and cultural heritage, which leads to the situations of sheer neglect we have seen happening in Brazilian public museums and national archives. It is all a very complex and intricate context that I won’t be able to summarize in this interview – I am barely touching the surface here, just to provide a quick picture of it to you; but, in fact, as the extreme right-wing takes power in Brazil in 2019, with Bolsonaro, all those cruel situations I have briefly named to you here have escalated (as they have been encouraged and, sometimes, endorsed by those in power), taking us to witness those unbelievable, outrageous scenarios we – and the world – saw in 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022.

Regarding nature, of course climate crisis has also played a role in the wildfires that have happened recently, especially the ones in the Pantanal region, but the human factor, i.e. real people consciously setting fire (and, sometimes, taking advantage of the situation of climate crisis), has been far the main issue in Brazil.

Elizabeth Ransom: The landscapes that you photographed for this project are natural conservation sites in Brazil. What is the significance of each of these places and what was it like to travel to and photograph these locations?

Marilene Ribeiro: I have an emotional bond to and a great respect for all the places I have interacted with and photographed in OPEN FIRE, as these are sites where I have been immersed in and working at for over a decade. They mean a lot to me. They have taught me so much, in so many ways. Some of them I comfortably call home, that is what they are to me.

Well, reaching those sites is another story, it involves crossing rivers, canoeing, walking long distances sometimes, etc.. But, as I said to you, as I feel I’m going to where I belong, it’s all part of my way home.

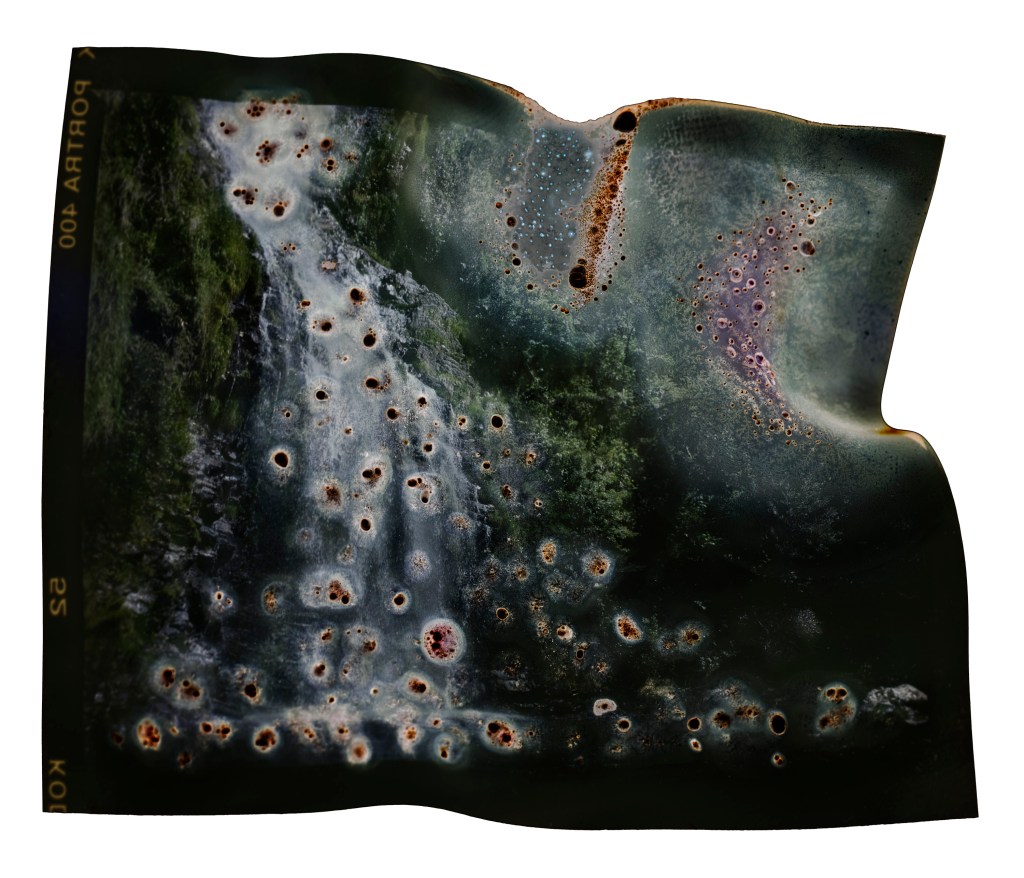

Elizabeth Ransom: To reproduce the acts of aggression that have been inflicted upon the natural landscape you burn photographic negatives, melting the plastic and burning holes through the emulsion. This process renders warped depictions of conservation sites in Brazil. Could you explain what led you to this process and the steps you took to create these images?

As I had wildfires as my subject of research before, I was very aware of the big picture, causes, consequences, statistics, diversity of contexts, Brazilian savannah, Amazon, etc.. But that thing of the ‘Day of Fire’ (which you can hear in one of Open Fire’s stories) and witnessing the clear dismantlement of Brazil’s environmental agencies by the Bolsonaro’s government in 2019 really got to me. So, as a visceral response to those things, in an impulse of resistance, the idea of using the photographic negative – which is so valuable in many aspects – as an instrument to convey the magnitude of what has been erased and denied to future generations as a consequence of cyclic fires, and in such coward and cruel fashion, came to my mind. So, to try to meet that goal, I would need to emulate the act and the role of the perpetrator, which, I tell you, took me a lot of effort, emotionally, I mean, as I would need to do something that would hurt me, as an individual and as a photographer. But this was the way the methodology would make sense and be suitable to the aim of the work.

Regarding the techniques employed in the burning of the photographic negatives: I researched and tested different sources of fire (match, lighter, etc..) as well as various ways of manipulating it against the celluloid and the photographic emulsion, until I eventually found the results that I considered appropriate for the work (in that regard: one of Open Fire’s stories is dedicated to describe that stage of the work – so striking it was to me that experience of burning my own negatives and, at the same time, those precious places).

Elizabeth Ransom: Alongside your photographs, you have included a series of excerpts from news stories, your own personal reflections on the situation, and quotes from the Brazilian Indigenous People’s Council. These texts provide contextual information while also sharing personal insights into those most affected by the fires. Can you tell us a little bit about your research methods and what it is like to include your own personal reflections?

Marilene Ribeiro: As I am exposing a contemporary issue from my standpoint (and I understand that, in a visual narrative that is thought and shaped, it is not possible to detach the storyteller’s standpoint from it), I considered important to openly acknowledge that everything that is being spotlight in Open Fire comes from my own experience, as an observer and researcher of this subject, but also as someone who cares about our natural and cultural landscapes, about our planet and our future. I wanted to be transparent about this point, yet, also wanted people to note that this violence and death that has happened by means of fire as a weapon is not a something punctual, nor restricted to my sole analysis or perception, it has been broadcasted by various well-known and reliable sources too – and it’ s been repeated over time. That’s why I understood that it was important to have these two things in dialogue in the work (i.e. news source and insights that happen to me while I develop the work), to set out the loop of destruction we are living in, in a very clear, yet also personal way. I considered important to share with the beholder my true and long-term commitment with the subject. The news source was a way I found to say: “look, this is not punctual, it is a pattern, it has identifiable causes, and it is unacceptable; will we let it carry on happening until we no longer have a single thing standing?”

Transposing part of what happens in Open Fire to a global scale: look at what has just happened in British Columbia, and in Greece a couple of months ago, and in Spain, last year, and in California, Argentina, Australia and again in British Columbia a couple of years ago. I mean, as our planet gets warmer and drier, wildfires tend to be much more aggressive, destructive and difficult to control than before – and scientists were aware about that and have warned us and decision makers about that too, but, unfortunately, scientists have not been taken seriously enough. These heart-breaking (and inadmissible) situations are happening as a cycle. And, every time they happen again, we lose a bit more of our incredible planet. There is no way of not caring about what is happening. To me, Open Fire is an act of resistance, through photography, and, at the same time, a call for action. My question is: “will we carry on passively watching this loop of shocking news as mere spectators?” I believe that each one of us, in different ways, can take an active role to help change this.

Elizabeth Ransom: Open Fire can be experienced as a multimedia online exhibition. Talk us through the process of creating this interactive digital exhibiting space and how audiences can engage with your research and creative practice online.

Open Fire comes to life through a grant awarded from the Brazil’s National Arts Foundation (Funarte) – the Marc Ferrez Photography Prize. At the time the prize was granted, it was part of its terms and conditions that the resulting work should be exhibited online only. So, I took this rule of the prize as an opportunity to make Open Fire available to as many people as possible (well, aware that unfortunately many in this world still cannot have internet access), as on the web one could interact with it at any time and from virtually any place, compared to when the work is exhibited in a constrained space and time (as part of a physical show in a gallery or museum, for instance). So, the web designer and I worked to put together an online platform where people could not only see the images but also access each story at the same time they look at each image of the work, so that the image before them could expand to its “real dimension” – I mean, the real dimension of what is being annihilated. Every story can be read (as it is available as a unique text that accompany every image) or listened to (as it is also available as an audio file that can be played by the web visitor – the audio consists of the text narrated in my own voice, as it has to do with my own experience with the subject, as I have explained here before). Also thinking about accessibility, the multimedia platform is available in both English and Portuguese languages and we carefully thought about making it friendly to those who are visually impaired too: it features high-contrast texts and audio descriptions that inform the web visitor about each image that it is on display on the screen. We had people who are visually impaired navigating and suggesting any improvement needed before we officially launched it, so that we could have it well-tuned.

I would like to say that, apart from the fund granted by The Brazil’s National Arts Foundation (Funarte), Open Fire came to life thanks to the support of the Brazilian Artmosphere Fine Art studio; so, I am very thankful to them for that too.

I finish by inviting everyone to check Open Fire online at www.openfireart.com and saying thank you, Lizzie, for this space to discuss the panorama of possibilities photography can provide us to research and to communicate the pressing issues of our times.

Open Fire has been recently awarded the POY Latam 2023 Carolina Hidalgo Vivar Prize https://poylatam.org

For more information about Marilene Ribeiro’s work please visit her website HERE