29 June 2023

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

The new publication KER by artist Eugenie Flochel investigates the lived experience of domestic violence and how survivors can use creative processes to heal. Flochel draws from her own personal story after an abusive relationship in her early twenties. Sadly she is not alone in this experience. In the United States “1 in 4 women and 1 in 9 men experience severe intimate partner physical violence, intimate partner contact sexual violence, and/or intimate partner stalking with impacts such as injury, fearfulness, post-traumatic stress disorder, use of victim services, contraction of sexually transmitted diseases, etc.” (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence). Flochel worked with female survivors as well as using her own experience to create works of art that challenge misconceptions around domestic violence and shines a light on the healing process.

Elizabeth Ransom: Your photobook KER uses a unique methodology combining alternative photographic processes such as lumen printing and polaroid lift with community workshops and self-portraiture to investigate the representation of the aftermath of domestic violence. This beautifully constructed publication tells not only your own personal narrative of healing and resilience but also that of other female survivors. Can you tell us what inspired you to tell these stories and why it is so important to represent life after violence and challenge misconceptions about domestic abuse?

Eugenie Flochel: Reasons behind KER are two-fold.

On the one hand, domestic violence is a cause very dear to my heart because it is my personal story. I experienced multiple forms of violence during my first relationship from the age of 18 to 23. Surviving violence has greatly shaped my interests as a woman and has influenced my practice as a photographer. I have come to use image-making as a cathartic process, experimenting with techniques, mediums and materials. Unfortunately, this issue is also a collective one as 1 in 3 women globally suffer from abuse and violence and 1 in 4 young women globally experience abuse from their intimate partner by the time they turn 25.

On the other hand, KER was born out of a frustrating lack of literature and representation in the media about the aftermath of domestic violence. As I was personally surviving abuse, I was overwhelmed by media representations of domestic violence that I found deeply unhelpful and lacking a sense of reality, authenticity and empathy for survivors and the general public. I also found very few narratives and art representations depicting what happened after surviving violence, namely the healing process. How do you keep mentally stable after abuse? How do you build self-esteem and confidence? How do you let go of rage, shame, guilt? How do you develop empathy, hope and faith instead? How do you ever trust and love again? And how do you represent the ungraspable? I also found from experience that art could serve as a great testimony of trauma and tap into the unconscious mind.

In light of the above, KER stemmed from a need to portray victims as survivors and to represent life after violence as a positive narrative of recovery and self- leadership to help challenge misconceptions about domestic abuse and erode the perspectives that are subjugated by guilt and shame to restore self-esteem.

Elizabeth Ransom: Since September 2022 you have conducted a series of mindful workshops for a group of six female survivors. The results of these gatherings have been included in the publication. Can you tell us a little bit about how you came to work with these survivors and how you navigated the creative process of these healing sessions?

Eugenie Flochel: When I started working on KER, it became very clear to me that I needed to work with female survivors directly in order to approach their own healing journeys in therapeutic and creative ways. I wanted to work with survivors from both France and the UK and as one thing led to another, I was incredibly lucky to be working with Le Filon, an amazing charity aiding women survivors living in extreme poverty in Paris that entrusted me instantly with my project and its endeavour. Throughout 5 sessions over 3 months, I started to build what has now become my method of Therapeutic Arts Workshops that I facilitate at various charities in London, engaging women to create a positive practice of participatory self portraiture employing various art forms including photography, painting, drawing and collage art while grounding them with a sound healing guided meditation and breathing techniques learned from my training as a yoga teacher. Given the women’s personal experiences at Le Filon, along with the fact that I had no training as a workshop facilitator other than being a survivor myself, I was very aware of my duty towards their stories to serve only as a meditator, offering them tools to develop their own creative practice and build personal narratives of hope, empathy and self-compassion. Through collective work and individual interviews, I was able to build incredibly meaningful relationships with the participants whose difficult pasts did not take away their sense of agency, joy and faith in life and love. These women are a true example of resilience and I genuinely feel so lucky to have crossed their paths.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series Eudemonia, you bury your negatives in a pot of violets for six weeks. This cathartic act of burial and unburial, working with the natural environment in a poetic collaboration visualizes the healing journey. This process allows the elements to interact with the surface of the emulsion to be distorted and transformed by the microbes in the soil. This process is unpredictable. What was it like to embrace chance and the unknown in this body of work? Can you share what inspired you to use alternative photographic processes for this project?

Eugenie Flochel: My series Eudemonia is probably one of the most difficult and gratifying work I made as it allowed me to completely let go of expectations, introduce the element of chance and surprise and collaborate with patience – inherently linked to the healing journey. Having no control over the process was incredible to me and the burial and unburial of the film were intensely experienced as an emotional rebirth that translated visually, finding resonance to time, place and process.

The idea came quite organically as I spent a lot of time on my terrace last summer, working on my own healing journey as part of KER. It just naturally crossed my mind one day that it did make sense symbolically and emotionally to me to bury a film canister and let nature take ownership of the photographic body.

The funny thing is that I did not then know that violets symbolized memory and forgiveness – the surprises in life!

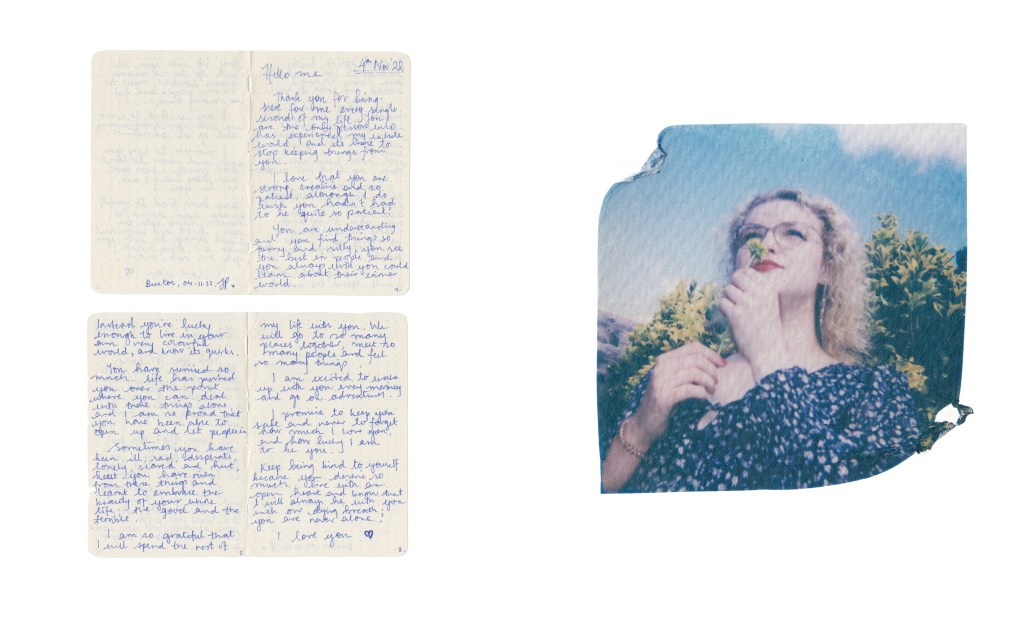

Elizabeth Ransom: Portraits of Resilience combines handwritten letters and portraits of women who have a painful history of psychological, physical, and/or sexual violence created using the Polaroid lift method. Can you tell us about the significance of the locations in which these portraits were taken and how the Polaroid lift technique symbolizes their experience? Furthermore, what do the handwritten notes and questionnaires reveal?

Eugenie Flochel: As part of my Portraits of Resilience series, I was researching female survivors whose healing journeys had navigated creative and artistic expression, to show how art could serve as a catalyst for recovery, liberation and hopeful narratives. All these women’s healing paths crossed music, yoga, content production, writing, sophrology and art. Meeting them in person, at their home, in their own habitat, where they felt safe and empowered, was critical to me to develop an authentic and genuine series about their own stories of healing. I was lucky to be awarded the Procter & Gamble Better Lives that entirely funded my project which allowed me to travel across France and the UK to meet them. Some of the photos were taken in their bedroom, garden, terraces or favorite café, as long as it positively represented them. The Polaroid lift technique was very important to me because it was an important signifier of the way they had freed themselves from abuse and extracted themselves from their past to rebuild on safer foundations. The technique is also very emotional in its process and leaves marks behind, adding texture and depth to the image. What the self-love letters and questionnaires revealed was a high level of faith, gratitude, empathy and self-awareness that guides them towards recovery, forgiveness and liberation.

Elizabeth Ransom: KER recontextualizes the narrative surrounding survivors of domestic violence by allowing the individual lived experience of healing to be brought to the forefront. It gives space for compassion and freedom of expression. From your experience collaborating with survivors and creating work about your own personal experience, how do you think photography can be used as a feminist tool to advocate for social change?

Eugenie Flochel: I am first and foremost convinced that art heals the hearts and minds. Any artistic expression has the power to help people navigate pain in meaningful and truthful ways. To me, photography has a dual way of both depicting reality, and distorting it. I chose to use the latter form for KER, and I think that it allowed me to explore portraiture here in the widest sense to offer a more nuanced appreciation of survival for both survivors and viewers.

Photography also helped create an emotional and safe space for survivors to tell their stories of recovery with their own words, means and terms. I believe this in turn established a new space, one that is hybrid, in-between places of trauma acknowledgement and healing.

KER used photography as an expanded medium, a feminist practice and a social participatory act, necessary tools for me to operate social change and positively impact the lives of women, survivors and society. My sincere hope is that by chronicling my lived experience surviving abuse and that of other female survivors through photography, I was able to communicate complex narratives within a public discourse and engage different audiences situated within multiple arenas : the social, the political, the artistic.

For more information about Eugenie Flochel’s practice please visit her website HERE

References:

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Statistics. At: https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS. Accessed (06/29/2023).

Leave a comment