25 May 2023

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

According to the World Health Organization as of “17 May 2023, there have been 766,440,796 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6,932,591 deaths, reported to WHO” (World Health Organization). For Miami based photographer RemiJin Camping the death of her father-in-law from COVID-19 in 2020 resulted in a trip to El Salvador where Camping used the photogravure process to document her husband’s family home. This project tells the story of migration as well as investigating the importance of family, the impact of time and the overwhelming experience of loss.

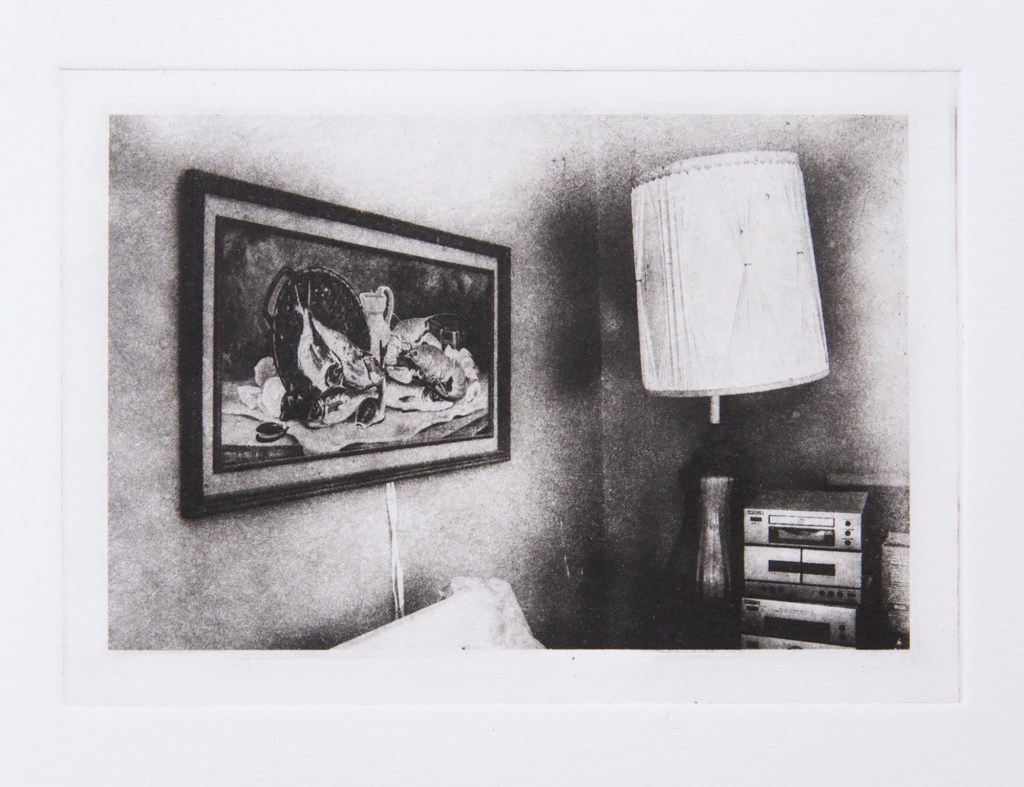

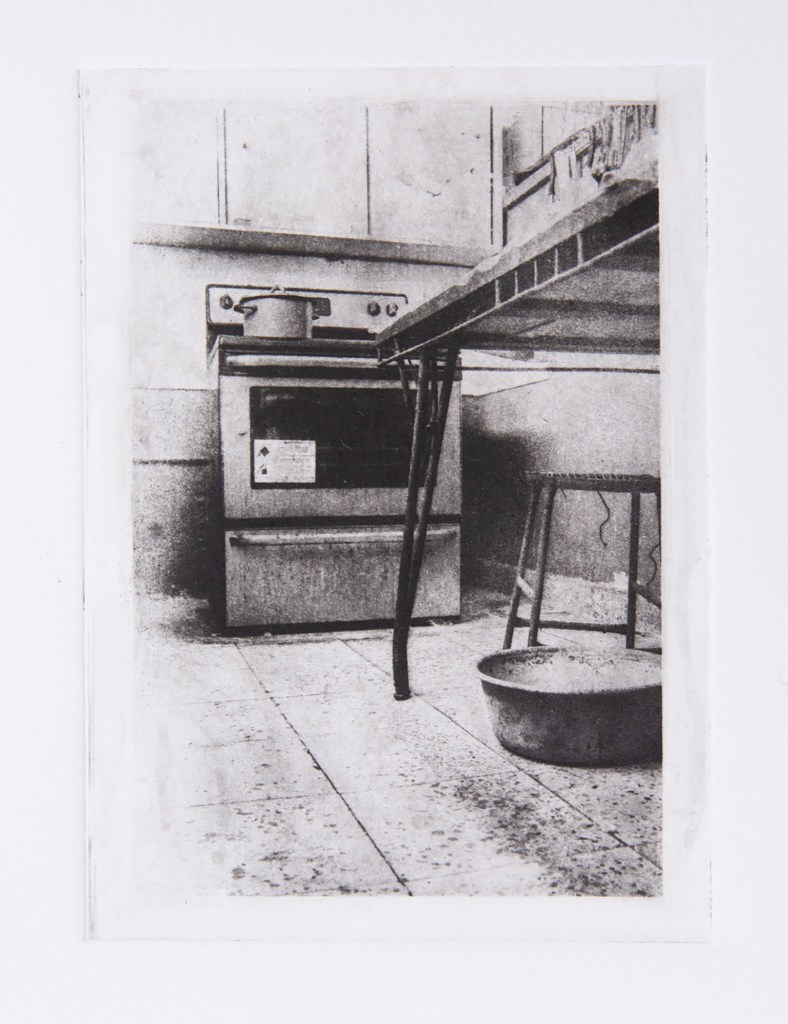

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series He Will Be Missed you create delicate black and white images of interior spaces using the historic photogravure printing process to tell the story of loss, family, and grief after the passing of your father-in-law in 2020 to COVID-19. Could you explain what photogravure is and why you chose to use this process for your body of work?

RemiJin Camping: Photogravures are different from other photographic processes in that with other processes the image is typically created directly onto a paper, metal, or cloth substrate. Photogravures have a few more intermediary steps before the final image is printed onto paper. The photogravures in this series are made from polymer plates, slightly different from the original copperplate photogravures and much safer for your health during the making process as the only liquids used are water and water-based inks. The plates I use are comprised of a steel backing and have an ultraviolet light sensitive coating of a polymer plastic for the surface. It is in this polymer coating surface where the image is etched by ultraviolet light, carving into the surface, and thus creating a textural recreation of the image. My original images were made with a digital camera and edited in photo editing software, then printed as positive black and white image onto a clear substrate. The image needs to be printed on the clear substrate because in order to etch the image into the plate it must be placed directly onto the polymer sensitive side of the plate, sandwiched tightly together in a contact frame, and then exposed to UV light using a box light unit with a specific UV wavelength. After exposure, the plate is washed in water to develop the image, making the plate etches deeper and ready for inking. Ink is gently rubbed into the plate, making sure to fill the etches with enough ink but not wiping away too much that the image won’t print. A delicate hand and lots of patience is necessary for this part. Once the plate is inked it is placed in an etching press with a damp paper on top of it. The pressure of pressing the plate and damp paper together transfers the ink sitting in the grooves of the plate into the paper itself, creating the final impression, the photograph.

It is hard to explain why I choose a process for making my photographs, a lot of my work is made intuitively, where an urge comes over me to create as a reaction to emotions and people’s stories. There is something internal that happens in the initial decision making, and at that moment is when it just clicks perfectly for a process to go with a body of work. It is during the making process and after the work is made where I can question the reasonings for what I make, get the answers. It took some time to figure out why I chose photogravures for this body of work; it had to do with the act of making the prints and with how the final images came out. Making a photogravure is very slow and methodical. Each of the many steps along the way takes practice, takes patience, and takes time. In a way, it relates to the grieving process. Grieving takes practice, patience, and time to heal, to get to acceptance. Sometimes that means enveloping yourself in a complicated process where the initial photograph is made and deteriorates with each step along the way.

Elizabeth Ransom: This was the first time in fourteen years that your husband had returned to his home country of El Salvador and the first time you had visited your husband’s place of origin. Could you tell us a little bit about your husband’s migration story? What was it like for you to journey to a place that holds such significance for your husband and to learn about his family’s history under such difficult circumstances?

RemiJin Camping: My husband’s migration story is an unorthodox one. Just before he was about to start college back home, he was able to avoid getting kidnapped for ransom. In the early 2000’s it was rampant in many countries, his being one of them. He fortunately was aware enough of his surroundings to know that he was being followed while walking home from bowling practice. He ducked into a nearby pharmacy, they have armed guards there, told the guard what was happening, and the guard closed the doors and called the police. The kidnappers had pre-emptively called his parents for the ransom, so they had already thought he was taken and had the police at his house when he called home. The very next day, he was on a plane to his uncle in Miami to find a school and start studying college here in the States.

Travelling back to his country was rife with emotions, from both of us. I had been wanting to go for years, he was too afraid to travel back. His parents also were too afraid for him to come back so it just never happened, until there was no way to avoid going back. There was excitement, anticipation, anxiety, dread, sadness, grief, and fear all wrapped together. I had never even seen a photo of his home, so I knew very little visually of his home life. Of course, we talk about everything, and I would hear stories of his growing up and his friends, and his country but the picture I had in my head of where he came from was fuzzy at best. It was overwhelming with the grief, but the country felt very familiar to me as it reminded me of the Philippines. For him, it was jarring that his home was practically the same, but in a more deteriorated state.

Elizabeth Ransom: The intimate domestic scenes that you have photographed convey the “decayed memories” of what once was. A past that can never truly be revisited and a personally significant location that will now be forever changed. As a Filipina-Dutch American, the experience of migration is something you are familiar with as well. Often the connection to the homeland and the construction of a migrant’s identity is formed through the passing down of stories from generation to generation and the ability of the family to keep the homeland alive. Now that one of those ties has been severed has this changed how you both feel about your relationship to El Salvador and your migrant identities?

RemiJin Camping: There is a duality of self that happens when one migrates from one country to another. And this duality starts long before the loss of a loved one. There is always that connection to where you came from and the people you were surrounded by, but at some point in time, you start to diverge and become this new person, one who has put down new roots and connections in this new location. For us, we embraced the new people we have become in this new place. Aware of where we came from, certainly missing the food, but enjoying the new opportunities and interests that we can explore here. After his father’s passing, we have travelled to El Salvador for vacations and visiting his Mom, but he has said he could not live there anymore, not because of what happened in the past, but because the person he is today doesn’t fit in over there anymore. The same goes for me, I felt like an outsider when I lived in the Philippines, and I don’t feel fully American living here, but the person I am today is at home in Florida and content with being this mix of duality of self, surrounded by family and friends from all around the globe.

Elizabeth Ransom: Grief is a powerful theme in this work. Your photogravure images emanate a soft, ethereal, almost ghost-like quality. Did the slower pace of the photogravure process aid in healing from such a tragic loss?

RemiJin Camping: Absolutely. I wasn’t extremely close with my father-in-law, but I was very close with my Dad who passed away twelve years prior to my father-in-law. When my father-in-law passed, all those feelings of grief and sadness related to when my Dad passing came flooding back, reminding me of my own loss all over again, nearly as sharp as the first time. I am also a very empathetic person and the feelings emanating from my husband and mother-in-law at times was so overwhelming the only way I could process and express the emotions I was feeling was by making this body of work. The methodical nature of making the photogravures became ritualistic, a need to melt away the hours and feelings, to be wholly engulfed with each tedious step along the way, alone with my thoughts, emotions, and the work.

Elizabeth Ransom: Often a person’s objects and private spaces can inform the viewer of the true nature of a subject and reveal untold stories. What was it like to encounter your Father-in-law’s belongings in such an intimate way? Can you expand on the significance of the spaces that you photographed?

RemiJin Camping: It was interesting in that it was about my Father-in-law as much as it was about my mother-in-law as well as my husband. It was their home, and my father-in-law only did the bare minimum for repairs to keep the home liveable once my husband moved away. My father-in-law never spent more than needed, never bought more than needed, wouldn’t get rid of things even if they were broken. Now, my mother-in-law was left behind, living in this home by herself. She was the one who had made it a home, who added the wall art and the trinkets, who made the meals and took care of the family. My husband’s room now cluttered but only slightly changed, with his TVs from his youth where he would play video games still there, unused and not functioning.

I felt compelled to photograph their home, a way to preserve that moment in time that was a transition for all of them; my father-in-law passing on from a long-lived life, my mother-in-law to an empty home, and my husband to seeing his past that was no longer like his memories.

For more information about RemiJin Camping’s practice please visit her website HERE

References:

World Health Organization. “WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.” World Health Organization. 23 May 2023. https://covid19.who.int/.

Leave a comment