25 April 2023

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

In France, on average over the past three years, 180 cases of physical aggression per year have been reported to SOS Homophobia. That’s one attack every two days. 34% of these attacks take place in public spaces. 70% are associated with blows and injuries. French artist, Cendre, uses alternative photographic processes such as film soup to navigate trauma and healing in their new work Minuit Brûle.

Elizabeth Ransom: Your newest body of work Minuit Brûle (Midnight Burns) is a deeply personal piece that recounts your own experience of a homophobic attack that took place in Bordeaux in 2015. This incredible work investigates trauma, homophobic aggression, and gender politics. Can you tell us about the events that led to the creation of this empowering project?

Cendre: I never planned to start a project about my trauma. When I started to take my art seriously, I wrote an oath and read it out loud in the summer of 2021 in front of the sea. This oath is about dedicating my art to the relationship between human beings and the environment. To create new images and open up possibilities. A year later, summer 2022, I am at the Rencontres de la photographie in Arles during the opening week. One morning I get up to listen to the exhibition tour led by the artists of the Discovery Prize of the Louis Roederer Foundation. It’s a total shock when I hear Rodrigo Masina Pinheiro and Gal Cipreste talk about their series GH. GAL & HIROSHIMA. These two artists worked on their experiences as queer people, in particular, a traumatic event in the childhood of Rodrigo Masina Pinheiro who was stoned in the street on their way home from school. Their story moved me and I realized that maybe I too had something to say, as a survivor. My story is different and at the same time similar. Mine was in 2015, I was 23 years old, I was coming home from a party around 3am on a summer evening. I had been drinking, I lived in Bordeaux in a big city. A group of people shouted lesbophobic slurs at me. I responded and kept on walking. But these people ran after me and beat me up in the street. Like Rodrigo Masina Pinheiro, I was identified as prey by my looks. On the other hand, contrary to the work of Rodrigo and Gal, what characterizes Minuit Brûle is rage, a very strong anger in response to the indifference and injustice that I went through. In my research notebook, I wrote two intentions:

- Most of all, this is for all of us who never made it.

- I make this work out of rage for you to be afraid. Because I’m not anymore.

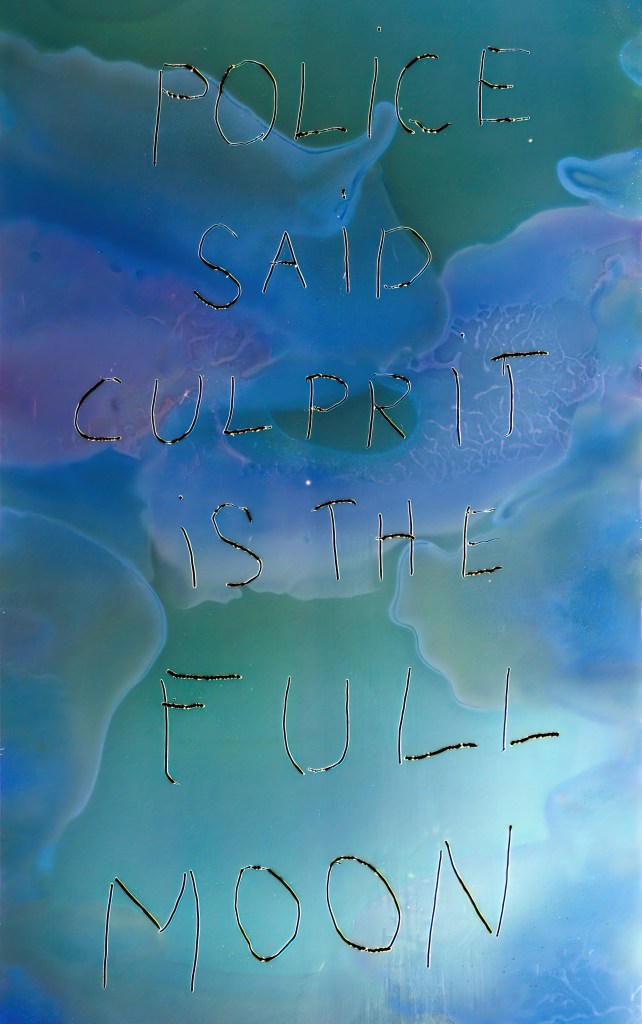

Elizabeth Ransom: When you went to file your complaint, the policeman justified this hideous act of aggression as a result of the full moon, minimizing your experience and dismissing its significance. Could you talk to us about the symbolism of the moon within your work and the role it plays?

Cendre: The moon is a celestial body that has fascinated human beings for a very long time. In different mythologies, gods or goddesses are associated with the moon, in legends or tales, it is easy to imagine Little Red Riding Hood or Snow White in the forest, at night, making their way in the moonlight. In my work, I am inspired by the symbolism of the major arcana XVIII of the tarot, the moon. This card is associated with the shadow realm, primary fears, blockages and repressed wounds. The light of the moon illuminates darkness but also makes shadows appear, one can easily get lost under the moonlight. When I started Minuit Brûle, it was obvious that the moon would have a central place. Beyond what the policeman told me, it is the whole imagery of the night that I want to invoke. People assigned women at birth are being told in our societies : “don’t go out too late”, “don’t get back home alone”, “don’t answer”. That night, I transgressed all of this, I took all the liberties heterosexual cis men take all the time and I paid the price, like many others before me and many after. I always had the feeling that if the policeman had taken the liberty of telling me that my attack was linked to the full moon, it was perhaps because he saw a 23-year-old young woman in front of him, who would not have responded. As if he brought a rational explanation to the unthinkable while he appealed to the irrational to explain the ordinary.

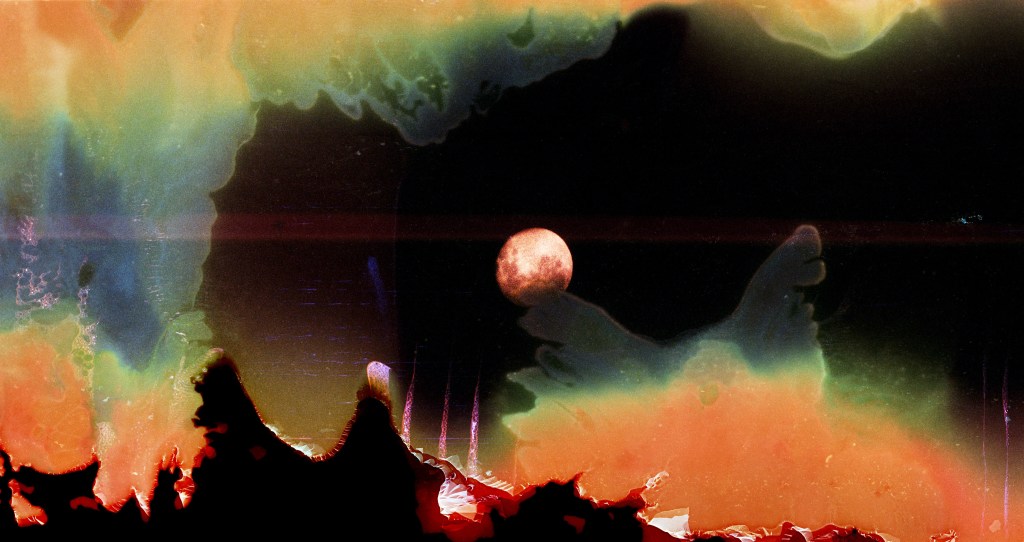

Elizabeth Ransom: Minuit Brûle uses a combination of art making methods including poetry, cyanotype, text, and film soup where you soak photographic film in your own blood. Can you tell us about your creative process and why you chose these very particular techniques to convey your concept?

Cendre: My creative process is at the same time very organized and very intuitive. I always start a new project by making a mind map of all the subjects that interest me within the project (for Minuit Brûle it was: the moon – the passers-by – the complaint – the body). I start from these themes and I associate them with techniques I know, in experimental photography, but generally in all the mediums that are part of my practice. This mind map structure is my starting point for exploration, on paper I allow myself all the possibilities and then it is by taking certain paths that the project will be shaped step by step. I make no distinction between mediums, they are all part of my practice, still image, text, moving image and volume bring different perspectives to the project and allow, I think, a better understanding of the different layers that compose it.

I started Minuit Brûle with reclaiming my complaint. In 2015, I wrote almost nothing following the attack, I even threw away the notebook that the psychologist had asked me to keep. I only had left the 9 pages of the complaint filed, kept in my drawer of administrative documents. I took the time to reread everything, which was very hard, I saw this filing of a complaint as a document that had frozen my experience in a set of sentences that do not reflect the injustice and indifference to which I was confronted. The idea of using cyanotype to reclaim my complaint appeared quickly, it was a way to reveal another story, the dark cyan of the cyanotype making the letters almost disappear, in favor of a more accurate image of my feelings. For the film soup, I immediately knew that I wanted to work with my blood. This is an idea that I had for a long time, I wrote in a notebook from 2020 ‘blood for the moon’. In Minuit Brûle, I perceive the film altered by my blood as a sort of extension of my body. I can’t recreate what my body has been through, but I can make the film become like a piece of my flesh to take photographs through. The easiest blood to get is my menstrual blood, cyclical, like the moon, thick and dark. Menstrual blood is also still often perceived as something dirty, which we do not show or talk about, a bit like trauma.

Elizabeth Ransom: As an artist how do you navigate working with such personal themes? Does the creative process act as a cathartic outlet or does reliving some of these traumatic moments negatively impact on your own mental health, and if so, do you have any self-care practices that enable you to make this kind of work?

It’s hard, I’m not going to lie. It is knowing how to be extremely vulnerable at all stages: during the creative process, when writing the texts, when talking about it, when showing the images. Rejection is very hard with this type of project. Don’t get me wrong, rejection is a big part of the artistic journey, you apply to funding or residency or exhibition and you’re not selected. But when you apply with this type of intimate project, it feels like they reject your story, your life, as if it’s not worth being shown.

For my part, I made the choice to be followed by a psychologist specialized in trauma for 6 months. In 2015 following the assault, I had therapy, but 7 years later I felt the need to be accompanied and it was a very good decision. I was able to talk every month about what I was going through, what the creative process brought out and it helped me a lot. I keep a notebook where I write all my creative process but also my feelings. I externalize in this way and at the same time it enlightens me on the directions to take. I would say that you have to know how to take your time, listen to yourself and accept what you are able and not able to do. There are limits not to cross and it’s good to acknowledge them. Recently, I went through a blockage: I couldn’t plan a trip to Bordeaux, the city where I was assaulted. A series of events finally pushed me to go there for 3 days. I was able to take photographs, think about the next steps and see certain places again, this time as an observer. Now I really want to go back, I am looking for funding and residency opportunities to be able to continue the series.

For more information about Cendre’s work please visit their website HERE

Leave a comment