25 March 2023

Interviewed by: Elizabeth Ransom

The UK based photographic artist Liz Harrington utilizes the camera-less photography technique known as cyanotype to collaborate with the natural landscape. These striking Prussian blue prints are used as a device to articulate the fragility of local environments. While the abstraction within Harrington’s work renders contemporary images saturated in gradations of blue, the cyanotype process itself is one of the earliest photographic techniques in existence.

Elizabeth Ransom: In your series ‘Where land runs out’ you use the camera-less photography process called cyanotypes to discuss the changing and fragile landscape of Shingle Street Beach in Suffolk. Could you tell us a little bit about what cyanotypes are and what led you to use this very specific process in your work?

Liz Harrington: Cyanotype is one of the earliest photographic processes, created in 1842 by Sir John Herschel – it is an iron-based process that creates a cyan blue image. It is a simple process, requiring UV light to expose the image, and water to develop and fix it. In the 1840s cyanotype was used by botanist Anna Atkins, a friend of Herschel, to document British algae and she created what is regarded as the first photobook, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, in 1843, a key inspiration for me.

Although I made my first cyanotype in 2009 it wasn’t until 2017, when I moved into my studio at Digswell Arts in Letchworth Garden City, that I first started using this process in my work. I had no easy access to a darkroom, and it was not possible to set up a safe, usable space in my studio, so this constraint meant that I had to look to alternatives. I had loved trying out the cyanotype process previously, it’s one of the easier techniques, is non-toxic and is a great way to start experimenting with alternative photographic processes. It was also summer so I was able to work outdoors, which was naturally appealing to me!

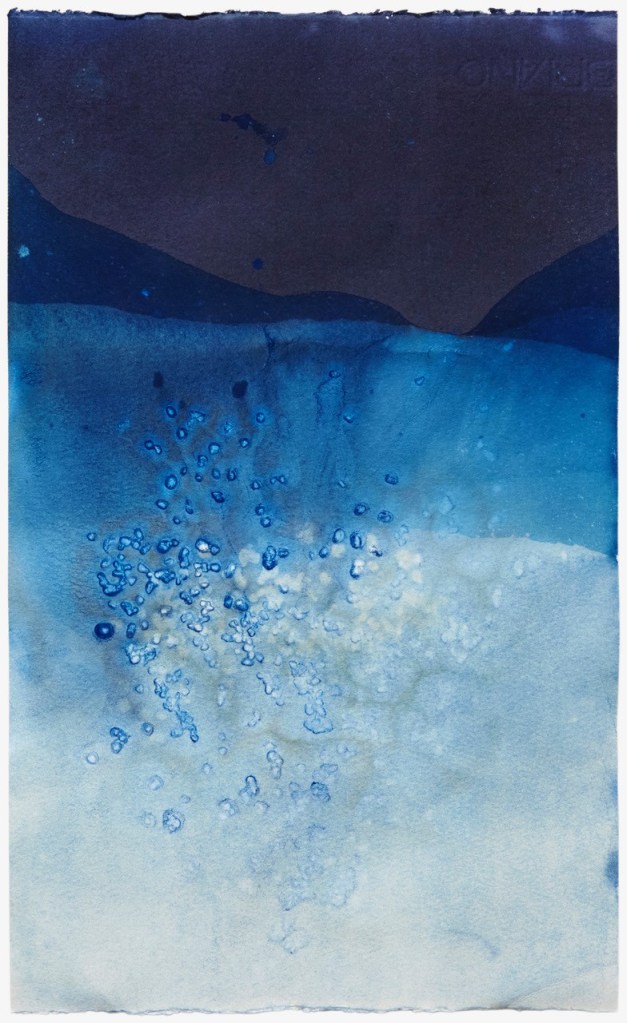

As well as making numerous photograms of plants, flowers, objects, I was interested in experimenting with the actual process itself, taking it back to its essence. Process is an important part of my work, as is a connection to the environment and place – be it physically creating the work in a specific environment or using, or collaborating with, elements from it. As cyanotype uses UV light and water, and inspired by Anna Atkins, I took some cyanotype coated paper on a trip to the Norfolk coast and started experimenting making abstract images and landscapes on the beach. Being able to collaborate with nature and the elements, capturing the physical, unseen traces of the waves, wind and sand at the shoreline eventually led to my project Where Land Runs Out and the cyanotype works made on Shingle Street beach in Suffolk.

Elizabeth Ransom: The location where you created ‘Where Land Runs Out’ is crucial to the discussion around coastal erosion and sea level rising in the UK. What is happening in Shingle Street Beach that inspired you to make this work?

Liz Harrington: The east coast of England is a particularly vulnerable part of the British coastline. I had been visiting Orfordness, which is just north of Shingle Street beach, since 2009 and was acutely aware of the impact of longshore drift on the area, climate change and risks from the encroaching sea.

I also have a background in geography, with a keen interest in coastal and river environments, and wanted to expand a project I was already working on around Orfordness to reflect this fragile and changeable landscape. Working with cyanotype felt like a natural progression from my earlier experiments with this process and enabled me to physically work in the environment. Due to practical reasons and access challenges at Orfordness I chose instead to focus this work just along the coast at Shingle Street beach.

Shingle Street beach is listed as a Site of Special Scientific Interest for its flora, fauna and geology and is part of the Suffolk Coast & Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Like Orfordness, it is a desolate landscape, with a vast open expanse of shingle, subject to coastal erosion and sea level rises, exposed to rapid changes and at risk of disappearing. There is no active management or sea defence system to protect it, mainly due to the impact they might have further down the coast – so the coastline is just left to nature. Sediment deposits from longshore drift have also started to create a new Ness, or offshore banks, which only become visible at low tide; but they are vulnerable and constantly moving.

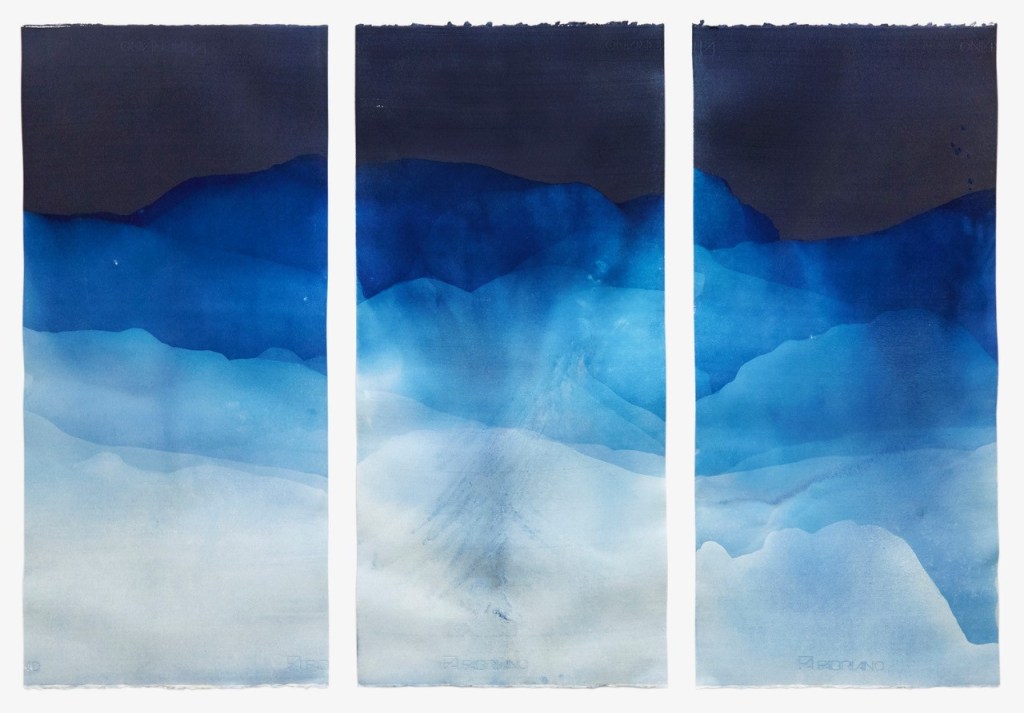

This constantly changing land and sea scape is all evidenced in the resulting images that were made by physically immersing the cyanotype paper in the sea during periods of high and low tide. Signs of sediment washed on to the paper, water marks from the wind and crashing waves, the paper torn and creased; all showing how changeable and fragile this coastal landscape is. The works are also not fully fixed, so continue to change over time – again as a reflection of this fragile and changing landscape.

Elizabeth Ransom: You have used the cyanotype process in a number of your projects including ‘Ephemeral Landscapes’ where you created works inspired by the micro landscapes caused by tides, rivers, rain, and snow. Could you explain the process behind the creation of these works?

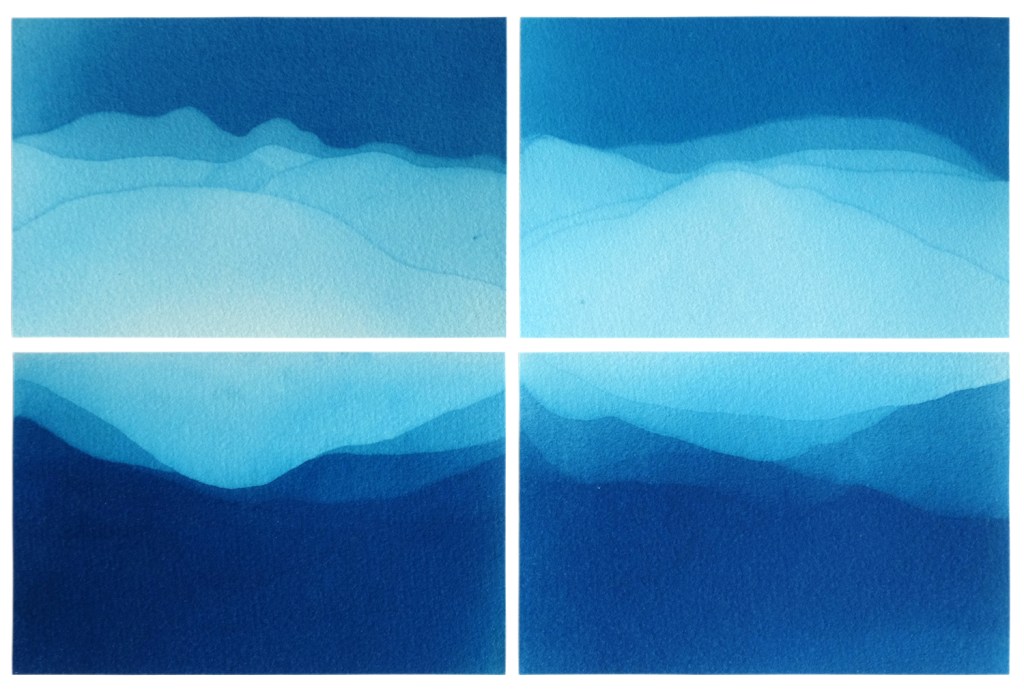

Liz Harrington: Ephemeral Landscapes was really the pre cursor to the works made at Shingle Street beach, but is also an ongoing project. It consists of camera-less cyanotype prints on paper as well as a handmade leporello book, which draw on the traditional Japanese aesthetics of wabi-sabi, the appreciation of beauty in imperfection and transience. Many of the works were made in situ, out in the environment – beach, rivers, lakes, gardens – but as I live a good two hours drive from the coast I decided to try and replicate the environment in my studio (I used to emulate river and coastal environments in the lab as a geography student in the 90s). This replicated environment gave more control to the final image, and can be evidenced in the cleaner aesthetic. Many of these images were then paired or made into grids to depict new and changing landscapes.

More recently, I also used the cyanotype process as part of a joint commission with Laurence Harding for the National Trust Flatford and Essex Cultural Diversity Project, support by Arts Council England, where we created a large-scale installation of handmade cyanotypes on silk to celebrate the 200th anniversary of John Constable’s The Hay Wain. For us it was important that these works were made in situ at Flatford, under the Suffolk sun, as well as to use water from the nearby River Stour to wash the prints and bring a sense of place into the work.

Elizabeth Ransom: Can you share any information about what you are working on now?

Liz Harrington: Last year I was awarded a Developing Your Creative Practice grant from Arts Council England. This was to test new working methods to make my practice more sustainable, as well as expand my work through use of natural inks and toners, collage and experimental moving image. Using imagery from a large archive of analogue (using expired film) and digital (iPhone) tree-based images, that I had photographed on walks in my local area since 2017, the new works include nearly 100 different cyanotypes, many of which have been toned using natural, tree-based toners. Some of these initial experiments can be seen on my Instagram page – I will be continuing with this project this year and ultimately plan to present the work as a handmade artist book.

For more information about Liz Harrington’s work please visit her website HERE